Paul de Zylva, Chris Gordon-Smith, Mike Childs15 Sep 2020

Summary

Friends of the Earth has for the first time mapped the availability of green space for people living in communities across England. This has been done by bringing together data on public green space, garden space, and open access land such as mountain, moor, heath, down or common land, and combining it with neighbourhood population data, including on ethnicity and income.1

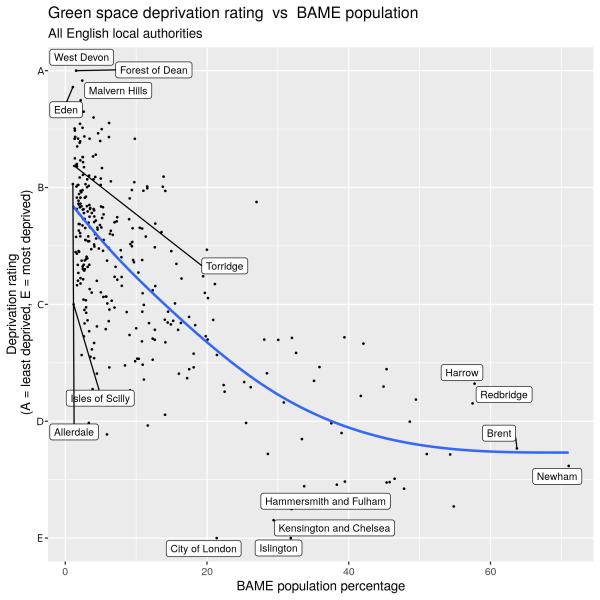

Our analysis reveals a marked disparity in access to green space and particularly a strong correlation between green space deprivation and ethnicity.

The stand-out finding is that if you are a person of black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) origin you are more than twice as likely as a white person to live in areas in England that are most deprived of green space. Almost 40% of people of BAME backgrounds live in England’s most green space-deprived neighbourhoods, compared to 14% of white people.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed existing inequalities, including those covered in this report. These have already been well documented, for example in the ground-breaking Marmot Review of health inequalities in England, and more recent work by The King’s Fund.2

Shortly before the pandemic, Health Secretary Matt Hancock spoke about the need to address inequalities:

“Tackling this postcode inequality matters to this government. It’s what we mean when we talk about ‘levelling up’. The underlying factors are a complex interaction between demography and economy. But because healthcare inequalities are geographically concentrated, it means we can take a targeted approach.”3

Friends of the Earth has produced this work to:

- Make the case for proper and sustained funding to raise both the quantity and quality of green space, especially in areas that lack it, so that the undoubted benefits flow to everyone.

- Provide data and evidence to empower the many local champions of green spaces across England.

- Influence the development and application of new green space standards by Natural England and others.

- Propose how protection and provision of green space would aid numerous central and local governmental aims, from health and community to land use and environment.

- Showcase examples of innovative approaches and good practice to illustrate the potential for action and to inspire change.

Visit our main website to access and use the map we've produced, or download the full report (PDF).

Introduction

"England’s green space gap" is the first comprehensive England-wide analysis to show the correlation between green space deprivation, income and race. It identifies the priority neighbourhoods most in need of green space investment if people in every part of England are to enjoy and benefit from the multiple roles green spaces provide.

Green space has been recognised for some time as vital infrastructure with unique and important benefits for everyone. However, it is only now that there are signs of this translating into joined-up thinking across government. For example, there is new governmental policy support and funding for social prescribing by primary care practitioners, which in many cases includes engagement with local green space.

Numerous reports have examined how people’s health and other government aims can be achieved though more and better contact with green space and nature, not least the seminal Marmot Review of health inequalities in England.4Studies have also tracked how a funding squeeze on green spaces, parks and nature areas is a false economy that ignores Benjamin Franklin’s axiom that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”.

The UK is blessed with a network of National Parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and other landscapes and spaces. The government’s Landscapes (Glover) Review heard and proposed ways to improve and extend access to them.5, 6 But it's also a reality that not everyone can readily visit a National Park or AONB and certainly not daily. In addition to these special areas, people need good quality green spaces on their doorsteps.

Boosting green spaces and nature is also needed to restore nature, mitigate heat stress, and flood risk resulting from climate change, and to address other important areas of public policy.

And in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is added urgency and appetite to ensure access for all to good quality local green spaces, for health and wellbeing through exercise, recreation, learning, and contact with others and with nature. The government, local authorities, communities and activists can all play their part.

Friends of the Earth has worked on nature issues since 1971, securing legal protections for UK wildlife and acting to prevent road building and similar ill-considered development. Even so, we recognise that our efforts on green space complement and pay tribute to long-standing work by many others in community and national organisations, including:

- The Open Spaces Society, whose campaigning for open spaces since 1865 includes early wins to protect Hampstead Heath, Wimbledon Common and Epping Forest. It has recently launched a charter for the protection, management, and creation of open spaces in England.7

- Fields in Trust, which has been legally protecting parks and green spaces of all types since forming 95 years ago as the National Playing Fields Association. It has pioneered the use of green space mapping with its annual Green Spaces Index.8

- The Conservation Volunteers (TCV) has been connecting people and green spaces for more than 60 years. Across the UK, TCV brings people together, many from disadvantaged backgrounds, to deliver lasting outcomes for the environment, communities, health and wellbeing, learning and skills.

- Thousands of local community and “Friends of...” groups have also saved, maintained and improved parks, wildlife areas and other green (and blue) spaces week in and week out, often working alongside local authorities to make the best of spaces with sparse funds and resources.

In its 2016 "State of UK Parks" report, the Heritage Lottery Fund estimated some 5,900 Friends Groups with 650,000 members. The National Federation of Parks and Green Spaces, the umbrella organisation for this still-growing movement, estimates that there are currently over 7,000 groups.

Even a report far longer than this one could not do justice to the extensive public health and other benefits these groups provide. England would be much worse off without them. We applaud their invaluable work and are pleased to showcase some national and international examples of what can be done for a relatively modest cost yet have big impacts (see Case Studies section below).

Why we need green space

Health and other benefits

Fields in Trust has shown that frequent personal use of parks and green spaces is worth over £30 billion a year to the UK population. That value translates into estimated savings for the NHS of at least £100 million a year from fewer GP visits.9Despite this, funding for green spaces and parks has not reflected the value of these cost savings to the nation for several decades, and they continue to face a funding crisis.

The multiple benefits of local green space and routine contact with nature include:

- Improved public health, both physical and mental.

- Reduced stress and improved wellbeing.

- Healthier early years’ and childhood development.

- Opportunities for informal and formal learning and improved educational attainment.

- Reduced health-related costs to society.

- Increased social cohesion within and between neighbourhoods and communities.

Access to green spaces for health is recognised and reflected in social prescribing by the NHS and the National Academy for Social Prescribing.10 Public Health England’s recent review of the health and wider social benefits of green space reported that.11

“Evidence shows that living in a greener environment can promote and protect good health, and aid in recovery from illness and help with managing poor health. People who have greater exposure to green space have a range of more favourable physiological outcomes. Greener environments are also associated with better mental health and wellbeing outcomes including reduced levels of depression, anxiety, and fatigue, and enhanced quality of life for both children and adults. Green space can help to bind communities together, reduce loneliness, and mitigate the negative effects of air pollution, excessive noise, heat and flooding. Disadvantaged groups appear to gain a larger health benefit and have reduced socioeconomic-related inequalities in health when living in greener communities, so green space and a greener urban environment can also be used as an important tool in the drive to build a fairer society.”

Environmental pressures and building resilience

The role and value of good quality green space in contributing to increased resilience are also increasingly understood, including those linked to environmental conditions such as a changing climate and declining nature, such as:

- Reduced noise pollution, which is estimated to have saved over £15 million in avoided loss of quality of life years in 2017.12

- Helping to reduce the risks and mitigate the effects of flooding.

- Moderating temperatures and harm from increasingly frequent heatwaves.

- Absorbing and storing carbon as part of action to keep our climate stable.

- A partial role in mitigating air pollution, saving £1.3 billion in health costs from avoided deaths, and fewer respiratory and cardiovascular hospital admissions, amounting to 27,500 years of life saved.13

- Supporting and boosting wild animal and plant species.

- Helping to maintain and restore healthy functioning natural ecosystems.

Public Health England has also recognised these added benefits:

“UK climate projections predict that heatwaves are likely to become more intense and more frequent in the future…Older age groups are more susceptible to the effects of heat, and there are indications that more deprived populations may often be disproportionately affected. There is strong evidence that in an urban context green space is associated with heat reduction. Research indicates there is a ‘park cool island’ effect of between 1.5-3.5°C, with a stronger cooling effect for larger urban green space, and that shade giving street trees also provide an important means of heat relief.”

Around 10% of neighbourhoods in north west England, the west Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber are classified as extremely socially heat-vulnerable, while London has 40% of the total number of areas regarded as extremely socially heat-vulnerable.14

COVID-19 and green space

Recognition of the value and the paucity of good quality green spaces and parks existed before 2020’s COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. In 2018, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak, speaking as then Minister for Parks and Green Spaces, said:

“Our parks are precious, and I want to improve access to them for everyone - including the young, isolated and the vulnerable.”15

The pandemic lockdown has brought both the role and the lack of good quality green space to the fore, as many people discovered local green spaces and parks for the first time or made more frequent use of them. The closure of some parks to avoid overcrowding compounded pressures on people’s sense of wellbeing and ability to cope, further highlighting deficiencies in green space provision and access.

Communities Secretary Robert Jenrick was prompted to declare:

“While the virus does not discriminate, we know that the lockdown is much harder for people who don’t have a lot of living space, a garden, or anywhere for their children to run around. People need parks.”16

There are also signs that parts of the government understand the pivotal role of green spaces perhaps more now than ever. As well as the comment “people need parks” in response to the pandemic, the government’s promise to “build back greener and better” speaks to an ambition that everyone has access to good quality parks and green spaces.

The government must now demonstrate it intends to follow through on its promises with the forthcoming Spending Review, the new standards being developed by Natural England for green infrastructure, and in its latest planning reforms (which as currently proposed could make the situation worse).

Where to invest and how much is needed?

Urban green space in England declined from 63% to 56% between 2001 and 2016.17 For the first time, Friends of the Earth’s data analysis and mapping identifies those neighbourhoods18 most deprived of green space, which most need investment. Access the map to see how each area fares, or download more details on the locations and analysis are available in our full report.

Sustained spending is needed across England, but some areas need investment more than others. That is not to say that better off areas do not need increased investment – they do. Most areas have experienced declining funds and subsequent impacts on the quality of green space for many years. For example, London’s population has grown by 11.2 per cent over the last ten years, while spending on green space has decreased by over 30 per cent, according to the London Green Space Commission.19

Fields in Trust’s 2015 survey found one in six people reported their local park or green space was at risk of being lost or built on20. When MPs investigated the predicament facing public parks, they reported:

"...parks are at a tipping point and face a period of decline with potentially severe consequences unless their vital contribution to areas such as public health, community integration and climate change mitigation is recognised.”21

How we've rated green space deprivation in England

Friends of the Earth’s data analysis has drawn on multiple government datasets to identify those neighbourhoods that are most deprived of green space. We devised an A to E rating system for each neighbourhood in England, dependent on:

- The quantity of green space – gardens and areas of public green space identified by the Office of National Statistics, plus areas of “open access land” identified by Natural England, which includes mountains, moors, heathland, downs and common land.

- The distance to access this public green space and open access land, using Natural England guidance that everybody should be within 5 minutes’ walk of 2 hectares of green space.

Neighbourhoods rated as E – the most deprived – are those where, on average, there are either:

- very small gardens22 and very small amounts of public green space/open access land; or,23

- very small gardens and small amounts of public green space/open access land24 more than 5 minutes’ walk for 75% or more of residents.

Neighbourhoods rated as A – the best for green space – have on average large or very large gardens and large or very large amounts of public green space/open access land.

Where should investment in green space be prioritised?

1,108 neighbourhoods in England are rated E and are home to almost 10 million people, roughly one fifth of the population. In addition, 955 neighbourhoods are rated D, which still represents very poor green space provision.

These should be the priority areas for investing in more green space, while also ensuring that high quality green space and other green infrastructure is in place in all areas (for example, street trees).

As noted above, there is a strong correlation between green space deprivation and ethnicity, and a correlation between green space deprivation and income. The graph below illustrates this finding.

How much would it cost?

In 2018, and for parks alone, the Parks Charter – endorsed by 24 national bodies and over 170 regional and local organisations – said spending around £2–£3 billion a year was needed for parks across the UK.25

The recent 2020 report for the National Trust, Sustrans, Create Streets, the Heritage Lottery Fund and others – including Andy Street and Marvin Rees, respectively the Mayors of the West Midlands and of Bristol – says that that the government should invest £5.5 billion of capital funding over 5 years to boost public access to green spaces, especially in areas lacking proper provision, together with £275 million in annual maintenance.26

The proposal includes the development of 10,000 km of streets planted with trees and the creation of 155 neighbourhood and 600 street parks in deprived areas, plus 9,200 upgraded parks and the creation of 7,500 km2 of peri‐urban parks across Great Britain.

Friends of the Earth endorses this call, although it is important to note that the £275 million annual maintenance cost does not include the additional expenditure needed to maintain existing green infrastructure, nor the funds to fully exploit the health and social benefits of community engagement in green space development, maintenance and use.

A capital funding programme of around £2 billion per year for the next 5 years, together with an additional and ongoing £2 billion on annual maintenance and community engagement, is more in line with what’s needed. This would properly improve and expand green space provision and green infrastructure across the UK, maintain its quality and lock in its benefits.

The sums involved may seem steep at first but the savings in health and other quality-of-life benefits would still dwarf these levels of expenditure.

The Parks Alliance has recently produced a comprehensive and compelling evidence-base and business case for the value of parks, covering the many and varied health, local economic, environmental, and wider community benefits. "Making Parks Count – the Case for Parks" states that:

“... parks in England deliver over £6.6 billion of health, climate change and environmental benefits each year including £2.2 billion in avoided health costs alone and are worth £140 per year to each urban resident. For every £1 spent on parks in England an estimated £7 in additional value for health and wellbeing and the environment is generated. The case clearly demonstrates that parks are a smart investment. Unfortunately, because these returns have never been properly understood, parks have suffered from years of underfunding and there remain gross inequalities in access to quality green spaces across the country. Making Parks Count presents the case for turning this around.”

Political context

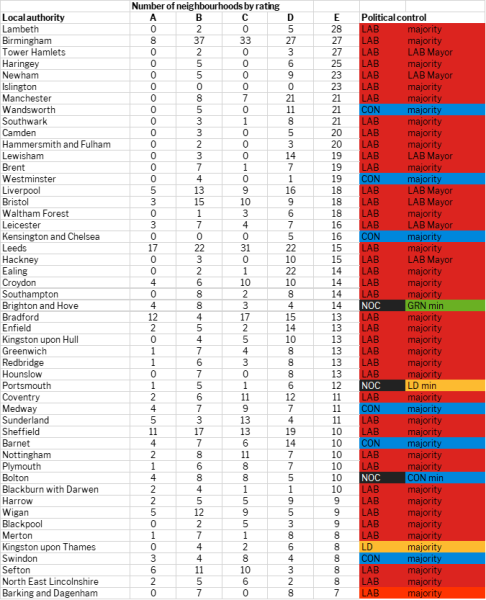

We have also looked at the correlation between the political control of councils and green space deprivation. Further detail is given in the full report. It is striking that most neighbourhoods that are rated E are under the control of Labour administrations.

Of the 50 local authority areas with most rated E neighbourhoods, 40 are Labour controlled, 6 are Conservative, 1 is Liberal Democrat, and in the remaining 3 councils there is no overall control (see table in appendix). Two-thirds of neighbourhoods rated E are in Labour council areas, while around a fifth are in Conservative-led councils.

Clearly, it would be wrong to suggest that just because the majority of neighbourhoods rated E are within Labour council areas that it's their fault; instead it's the result of many decades of neglect from national and local politicians of all political persuasions. But it does suggest that the government will get the full support of the main opposition party, if it honours its commitment to ensure that everyone in England has access to the quality and quantity of parks and green spaces needed for physical and mental health. But if it fails to do so, it will face significant and sustained political pressure from Labour and other parties.

Recommendations – the policy changes and actions needed

Money is not the only solution to the problem of green space deprivation, although clearly it is important. Friends of the Earth recommends that the government should:

Protect existing space in perpetuity. There should be a legal requirement to protect and enhance the quality of all existing public green space for people and nature. Existing green space can be protected through covenants and measures such as Fields in Trust’s Green Spaces for Good programme.27

Introduce a requirement to create new green space where provision is lacking. The idea that there's a lack of available space for new provision in some urban areas is laughable considering the amount of space given over to cars, particularly given that the number of drivers in those communities most deprived of green space is low. New street parks should be created by permanently closing some streets, as recommended by the National Trust and others. These are estimated to cost £3.3 million per kilometer.28 As one of the case studies featured below shows, existing green infrastructure like school grounds can be safely opened up for community use and benefit outside school hours.

Strengthen England’s land-use planning system not weaken it. Planning reform must ensure that existing parks and green spaces are protected, that good quality green space is part of new developments as standard, and that green spaces and parks are treated as part of the wider public realm, not as isolated oases. Local Plans and Supplementary Planning Documents must be informed by the development of ecologically coherent nature networks and green infrastructure strategies, and through a consideration of green space in the development of Joint Strategic Needs Assessments and Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategies.The current proposals for planning reform could take us backwards not forwards.

Invest in green spaces to level up the benefits. Ending the long-term decline in parks and green space funding, with ongoing commitments to finance £4-5 billion a year to 2024, with maintenance of steady levels so that once quality and quantity standards are established, they are maintained without the risks of stop-start investment.

Factor in cost savings and benefits to policies and decisions. The many and varied financial cost savings and benefits should be factored into policies and decisions about land use, the design and layout of development, and ongoing use and aftercare.

Ensure both quality and quantity of provision. The multi-functional role of green spaces and parks should be factored into aims and strategies for health and wellbeing, fitness and physical activity, skills and learning, and climate and nature. This requires new forms of working between national and local government and between departments.

Make parks, green space and green infrastructure a properly funded statutory service, ending the situation where local councils have run and managed parks and open spaces, but not as a statutory requirement.

Ensure green space is provided for and with people of all backgrounds, with funding for community engagement. Residents and users’ voices must be heard in the management of green spaces to ensure they are inclusive (for example, a Muslim community might want areas where women can meet away from men). Community involvement in the practical management of green space, such as planting and nature conservation, should also be encouraged and resourced, including through approaches such as social prescribing. Communities also hold a wealth of expertise on nature conservation, children’s play, outdoor learning and education. These and other resources can be used by local authorities and others, as part of the approach to skills, learning, and better use and management of spaces for people and nature. If the full social and health benefits from green spaces are to be realised, then ongoing funding of green spaces and green infrastructure needs to include funding for community engagement, as recommended earlier.

Make green spaces hubs for learning and skills. Green spaces, parks and nature areas should be places where people can acquire new skills, knowledge and confidence, both through informal outdoor learning, and formal skills and education strategies.

Green space case studies

We've showcased some case studies of community and civic action on green spaces from the UK and overseas. This is in recognition of the important role communities have in closing the green gap, and to underline the importance of cooperation between various parties, including the central role of community groups with their knowledge, expertise and enthusiasm.

Tees Valley, County Durham: Tees Heritage Park – renaissance of the river valley

https://www.groundwork.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/THP-Natural-England-Case-Study.pdf

Tees Heritage Park stretches from Yarm to Stockton in the Tees Valley, taking in all of the open land along the River Tees, including the Leven Valley and Bassleton Beck. For the first time, this attractive stretch of green space has a clear identity and formal planning designation, so that it can be promoted as a single park.

Despite being the common thread along which communities had thrived, the demise of the river-based economy meant people turned their back on the river and no longer saw it as an attractive place. Unloved and a dumping ground for rubbish, development was piecemeal, with little thought for connectivity or the potential for this important environmental asset to boost recreation, nature and wellbeing.

Formed in 2007, the Friends of Tees Heritage Park conceived Tees Heritage Park to bring about a renaissance of the river valley, celebrate its heritage and provide a unique amenity for the valley’s communities. The park is now identified as a major strategic initiative in the Tees Valley Green Infrastructure Strategy, which recognises that the “corridor concept” fits well with the physical structure of much of the Tees Valley sub-region. The strategy identifies the River Tees as a strategic wildlife corridor that provides a major route through urban areas and into the surrounding countryside, with opportunities to increase accessibility for residents.

Created through a partnership between Friends of Tees Heritage Park, Groundwork North East, the Environment Agency, the Canal & River Trust, Natural England, Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council and Tees Valley Wildlife Trust, the park officially opened in September 2012 with the completion of the first phase of the project.

Benefits to date include enhancements to the river corridor that improve accessibility for nearby communities. Formally defining the park has made it easier to protect wildlife in areas such as the River Leven corridor. Site visits with local schools resulted in pupils producing a large number of sculptures that inspired the on-site artworks. QR codes enable visitors to download information about the local wildlife and heritage.

By connecting and promoting the existing green space as a single park, this visionary project has reconnected local people to the river they once turned their backs on.

Kings Lynn, Norfolk: River Lane pitches – effective campaigning through the planning consultation process

River Lane pitches form part of a large area of open space within the North Lynn area of King’s Lynn, Norfolk. The fields are in a ward that has particularly poor health and deprivation demographics and is one of the top 25% most deprived wards in England.

35% of the adult population in the ward are identified as obese, putting it in the top 20% of obesity rates nationally. At 73.1 years, average life expectancy is in the bottom 20% for England. Within Kings Lynn, the ward has the highest rates of crime and antisocial behaviour and some of the highest rates of unemployment.

The entire space was originally proposed for a major housing development by the borough council within its Local Plan allocations. The River Lane pitches themselves were earmarked for the provision of 153 new houses. A community campaign began during the council’s consultation process on its plan and a large number of residents engaged throughout the consultation, vehemently objecting to the inclusion of the River Lane pitches.

The campaign was successful, with the council agreeing to remove the pitches from the development proposal. The tenacity of the residents’ association led the council to agree to legally protecting the land under Fields in Trust’s UK-wide Active Spaces project, which has protected 50 green spaces across the UK while supporting less active members of communities to get out and use their local parks.

The River Lane pitches project recruited local women who faced barriers to participation. Many young mothers lacked the support needed to take up physical activity, so the project introduced “buggy bootcamp” and family fitness sessions on River Lane pitches, with children in tow. This was complemented with a couch-to-5k scheme - in total, 62 women completed the programme, with many running their first 5k. River Lane pitches will now always be available for the Kings Lynn community to enjoy for both formal sport, and informal recreation, forever.

This case study was first published in Watch This Space, the Fields in Trust handbook for communities to champion and support their local green spaces with an easy-to-use guide to the planning system.

Future Proof Parks: getting young people involved in their green space heritage

https://www.groundwork.org.uk/projects/future-proof-parks/

Groundwork has partnered with Fields in Trust and the National Youth Agency to deliver “Future Proof Parks”, a National Lottery Heritage Fund programme (part of the £10 million “Kick the Dust”’ initiative), which aims to get more young people interested and involved in preserving their local park and green space heritage.

Over the course of the 3-year programme, which started in 2018, 880 young people from the West Midlands, East of England, West of England, North West and North East will learn more about their local historic park heritage. The overall aim is that at least 180 young people will join their local “Friends of…” park groups and volunteer to preserve the local spaces that matter to the communities they live in.

The project will also work with 60 “Friends of…” park groups, giving them the tools, encouragement, and support to get more local young people involved in their work and to see the benefits of cross-generational working. The programme also aims to kickstart crowdfunding campaigns which will help raise money for the local parks and to test new ways of generating income, as well as engaging the local community.

Future Proof Parks focuses on historic parks and heritage landscapes in five “hub” locations across England. In each hub, young people will be supported to give their time and talents to support local groups and heritage organisations:

East: Hertfordshire, Luton and Essex

North East: South Tyneside, South Shields, Gateshead, Sunderland and Durham

North West: Blackpool, Liverpool, Wigan and Lancashire

West: Bristol and South Gloucestershire

West Midlands: Smethwick, West Bromwich, Oldbury, Stourbridge, Dudley and Tipton

Paris, France: Cours Oasis - transforming a school playground

Paris has found an innovative way to creatively use existing space to improve the urban environment and provide breathing space in the middle of city streets.

As a consequence of climate breakdown, France is facing more frequent and more intense heatwaves. As part of its resilience strategy, and with the support of the EU’s Urban Innovative Actions programme, Paris is piloting the transformation of ten school playgrounds into communal spaces that are green, cool and pleasant retreats from rising summer temperatures.

The goal of Cours Oasis is to establish a model for future schoolyards, co-designed with the schools – teachers, students, parents and other local stakeholders. The 3-year project, from 2019 to 2021, provides ways for local people to participate in an innovative climate change project, with the potential to be involved in future planning to transform schoolyards into communal spaces.

The idea is to create spaces for locals to share, especially in the evening or during school holidays, with a mix of inventive play areas, quiet corners, water features, more greenery and garden-based learning. The project is collaborative from start to finish: children are involved in designing the play areas and the oasis is created after consultation with local people to meet their needs and expectations.

Project delivery partner Paris Councils for Architecture, Urbanism and Environment helps deliver the co-design phase, through workshops, training, community mobilisation and assessment.

The pilot project with ten schools will provide the opportunity to experiment, trying out new solutions for construction materials, urban furniture, plant varieties, neighbourhood engagement and participative democracy. These will all provide useful lessons, with the potential to create scalable and durable approaches to opening up school playgrounds as green lungs in the heart of the city.

Unfortunately, the opening of the school yards has been postponed due to the Covid-19 outbreaks and some of the citizen assembles suspended.

Hackney, London E5: 10xGreener – the postcode gardener

Many urban areas are deprived of green space and many city dwellers lack gardens, or the time and skills to make them thrive. Residents want greener and healthier streets, but projects can founder because it can be hard to maintain new planting.

Early in 2018, Friends of the Earth brought together residents in Daubeny Road, London E5 to explore how they could make their street 10xGreener. We found that there is a real appetite for neighbours to meet up and take action, but residents lacked the time or capacity to keep up the good work.

So Friends of the Earth ran a pilot scheme, bringing people together to increase and maintain the greenery and wildlife in and around Daubeny Road, while building a more connected community through gardening.

Crowdfunding raised over £6,500 to hire the UK’s first postcode gardener and paid for 350 hours of her time over a year to tackle maintenance and organise local residents in transforming the area. Kate Poland worked at “postcode level”, supported by delivery partner EcoActive and a group of passionate volunteers who co-created a vision of how the streets could be greened. This was not about helping people nurture their own gardens. It was about planting in public spaces and on-street yards, walls, windowsills, balconies that are publicly visible.

Using her own knowledge and skills, and resources especially created for the project, Kate brought people together, ran workshops, sowed seeds, planted in the margins and smashed up concrete to make space for nature. The initiative was very child-friendly and the group was strongly supported by the local primary school, where progress could be celebrated and plans and ideas shared. The residents continue to support the initiative and fundraise to retain the postcode gardener.

Friends of the Earth subsequently ran a competition with Crowdfunder to kickstart more postcode gardeners and received over 100 entries from across the country. The winner from Bideford, North Devon raised funds in November 2018 and hired their postcode gardener in 2019. Many other useful lessons have come from this pilot and Friends of the Earth is delighted that it has created the beginnings of a replicable model for different kinds of urban centres.

Tottenham, London: Lordship Rec – rescuing and transforming a public park

www.parkscommunity.org.uk https://lordshiprec.org.uk/works/

When park users launched the Friends of Lordship Rec in 2001, Tottenham’s largest public park was run down, unstaffed and almost abandoned. The Parks Service of cash-strapped Haringey Council was reduced to the bare bones of grass cutting and litter collection, the Rec’s buildings were semi-derelict, and anti-social behaviour was rife. Local people rarely ventured in, including those on the neighbouring council estates, Tower Gardens and Broadwater Farm, despite residents having little or no garden space.

But over the past two decades, determined community action, committed community / council partnership-working and substantial funding have resulted in the park’s transformation into a vibrant and beautiful multifunctional space for everyone to use, enjoy and benefit from.

Following years of effort, public consultation and collaboration, backed by massive and vocal support from local people, the park underwent a renaissance in 2012 with funding of £7 million from the Lottery, Haringey Council and other sources.

The park now has a new community-run hub with café and toilets and a new staffed depot. Existing buildings and facilities have been restored and a long-term commitment has been made to staffing and maintenance. Nature has been supported by turning a culverted river into a meandering flower-laden channel and more trees, meadows and flower beds have been planted. Bikers have not been forgotten, with a new BMX loop track.

A potent element of the ongoing programme is that community empowerment, enshrined in the park’s management plan, has been built into all decision-making. The Friends and user groups manage or part-manage various areas and facilities and co-manage the park as a whole with the council’s Parks Service.

Park usage has tripled. The Friends of Lordship Rec has 1400 members, and there are almost 20 different park user groups promoting cycling, wildlife, sports and fitness, managing the buildings, organising all kinds of events and involving all sections of the community.

This success story in a diverse, predominantly working-class area has been a trailblazer for something that can be replicated everywhere – the Friends host a project promoting community empowerment in green spaces throughout the UK.

Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Rotterdam, sterker door – Rotterdam onwards, stronger

https://dutchreview.com/cities/rotterdam-drops-233-million-on-green-spaces-and-they-look-incredible/

While many small local initiatives can make a neighbourhood greener and more attractive, an ambitious city-wide plan can deliver enormous benefits to many more people and can radically change the image of a city for its citizens and visitors alike.

As a major port, Rotterdam was bombed more extensively than any other Dutch city in WWII and in the scramble to rebuild, its concrete developments led to it being described as the “ugliest city in the Netherlands”. Bu that is about to change.

Rotterdam has invested 233 million Euros in seven different green city projects, aiming to complete them within a decade. The goal is to counter the negative effects of coronavirus and enhance the quality and appeal of the city, with a focus on adding green space to the urban environment. The changes will add a breath of fresh air that Rotterdam has seemed to lack, with fountains, trees, greenery, parks and more space for pedestrians and cyclists.

Innovative changes include the transformation of the roof of a railway viaduct, de Hofbogen, into a 2-km long walkway in the heart of the city, which will include a circular waterway.

The new 7-hectare Park Maashaven down by the harbour provides much needed green space and an area for festivals and events. The iconic Hofplein will be revamped with more trees and grass and the new Blaak park, combined with a decrease in traffic, will create cleaner air and less noise pollution. The new plans also include a more climate-friendly energy transition.

When complete, these transformations will add another aspect to the city’s existing urban experience, with spaces for people to breathe more freely, walk, cycle and hang out, designed with post-coronavirus in mind and the enhanced desire for access to green space that lockdowns have created. See the website above for illustrations.

Oldham: #LoveWhereYouLive – how fixing fly-tipping created a friendlier neighbourhood

https://www.hubbub.org.uk/Blogs/neighbourhoods-blog/can-community-action-cut-fly-tipping

https://www.hubbub.org.uk/lovewhereyoulive

Greening cities does not depend on creating dedicated spaces. It can also mean recognising that there can be enormous potential in overlooked and unloved places in the neighbourhood that can be transformed by a creative solution to a different problem.

Councils have to spend millions cleaning up urban fly-tipping and littering, while residents suffer the eyesores and sense of neglect that heaps of rubbish create. In Oldham, some back alleys running between the Victorian redbrick terraced houses were neglected, unattractive and unsafe rubbish-strewn waste grounds. No-one was taking responsibility for cleaning them up. Environmental charity Hubbub wanted to understand the causes of fly-tipping and to find solutions, by working with residents to transform 5 of these fly-tipped alleys into bright and friendly communal spaces.

Key to this transformation was winning the trust of residents and finding powerfully motivated women who wanted their neighbourhood to improve, because they wanted safe places for kids to play or a concern that the area was “going downhill”. Hubbub worked with local councillors, community support teams and local police to identify small bands of residents whose concern could be channelled to turn these alleys into safe, usable spaces.

In the areas where community action worked, the women leading the activities were able to earn the respect of neighbours and be a mutually supportive group with a clear idea of what they wanted. A range of activities proved to be successful in building pride of place, including community events, skills training and bright vibrant messaging. Hubbub turned these into an inspirational guide for others who want to transform shared spaces.

Three successful alleyway transformations with residents reported a 100% decrease in fly-tipping. What had started as a campaign about rubbish ended up helping build a sense of community, “transformed an environment that brought us continued frustration and despair into one that brings us joy and hope”, and helped people feel safer as they came to know their neighbours and their children used safe play areas.

However, the lessons from this project are that it is a slow, expensive, intensive process and requires ongoing commitment from partners and residents. Fly-tipping can be a sign of disconnected communities and can only be addressed by building trust and interaction between neighbours. It is not a quick fix.

Ghent, Belgium: the Red Carpet – a major new child-friendly route through an urban renewal area

https://rethinkingchildhood.com/2018/04/03/ghent-serious-child-friendly-urban-planning/

Ghent city authorities faced a challenge when planning the regeneration of Brugse Poort, one of the city’s poorest neighbourhoods, where public green space is scarce and very low quality. The 19th century district accounts for 4% of Ghent’s land surface but 25% of its population in a very dense urban fabric.

The plan became an urban renewal project, Oxygen for the Brugse Poort, to create extra public space in the neighbourhood, improve the housing stock and help foster cohesion in an economically disadvantaged area.

One strategic element is the Red Carpet, a 2 km traffic-calmed route through Brugse Poort that links neighbourhood children’s facilities, including a school, a kindergarten and several public spaces. The project involved extensive traffic calming, with distinctive red stones laid out in a herringbone pattern. New infrastructure included a pedestrian bridge, a multi-purpose public space that included informal sports facilities, and a walkway running right through Pierkespark, a historic building.

Elisabeth Belpaire, who worked on the project, drew several lessons from her experience:

- The spatial and physical re-structuring of the neighbourhood takes long-term planning and commitment, like buying up strategically-located properties over time that can be turned into new public and green space - adding “oxygen” to the neighbourhood.

- The Red Carpet has become the “soft spine”’ of the area, an axis connecting existing and new local services such as a library, kindergarten, and public spaces such as the newly created squares and parks. Increasing connectivity between the Brugse Poort and other neighbourhoods was also important for increasing walkability. It also meant strengthening connections with other neighbourhoods through bridges, literally and figuratively, and with city-level networks for pedestrians and cyclists.

- You need both political leadership and collaboration with grassroots organisations and youth representatives, through the establishment of a local coalition to achieve a high level of citizen participation. Both are key for the creation of a new identity and a “new memory” for the neighbourhood. While it is essential to keep people in the neighbourhood and avoid gentrification, it is a delicate balancing act to support the original communities as well as fostering economic growth and social mix.

Ghent has also proposed some major new green spaces, with four destination “green poles” either in place or on the way. Schoolyards are being refurbished in naturalistic ways. More than half of schools now have a green schoolyard, in a move inspired by a study visit to Berlin. Ghent is keen to rethink streets, with over 140 play streets alongside school streets (which are closed to traffic at certain times of the school day) and some of the region’s first “bike street” (fiets straat) projects, where bicycles have priority over cars.

Inverclyde, Scotland: Green Gym

Of all councils in Scotland, Inverclyde has the highest share of the most acutely deprived areas.29 A green space audit identified a number of underperforming green spaces. The Conservation Volunteers (TCV), working with Inverclyde Council and Glasgow & Clyde Valley Green Network Partnership, identified priority sites where environmental and accessibility improvements would be most beneficial and near communities with the greatest need.

TCV established a new Green Gym group and ran a 12-week Branching Out programme at Coves Reservoir Local Nature Reserve, working with a number of local partners, including the Scottish Association for Mental Health and Belville Community Garden Trust, to undertake green space improvements.

Woodland was managed and volunteers were trained in woodland maintenance techniques. Biodiversity was improved by the planting of over 350 trees and increasing the variety of wildflower species. Accessibility was improved by widening and clearing paths, improving drainage, and clearing and repairing steps.

Green Gym volunteers reported higher levels of physical activity and scored higher on the Short Warwick-Edinburgh mental wellbeing scale after taking part. Feedback included:

“Anxiety stops me from sleeping most nights but after the Green Gym I sleep really well.”

“I used to just go to the Green Gym but now I go walking and to the gym sometimes as well.”

“The Green Gym is very important for my physical and mental health as it’s the only time in the week that I get out of the house.”

A self-sustaining group of volunteers arose from this project and the Friends of Coves Nature Reserve are now a volunteer-led group, running weekly land management sessions and monthly community litter picks.

Leicester City: Rolleston Green Gym

Rolleston Green Gym was established in the grounds of Rolleston Primary School in June 2019 to provide intergenerational activities, including food growing and wildlife improvement in local green spaces.

The Green Gym enjoys strong support from local communities, including Eyres Monsell, which is in the lowest quintile of the 2015 Index of Multiple Deprivation among Leicester City communities. It’s also supported by Harborough District Council and Saffron Health Practice, which hosts regular giveaways of spare plants and promotes the project to patients.

David, a local single parent, discovered the Green Gym through his son, who is a regular attendee. David had faced many challenges in life, affecting his health and wellbeing, including feeling isolated from his community, and was looking for new opportunities to connect with other people.

He developed strong practical, creative, leadership and organisational skills and, one year on, is undertaking further training to gain the skills to become a TCV Volunteer Officer and support the Green Gym to become independent and self-sustaining. As David says:

“I have made new friends and learned to deal with people that I would not usually get on with. It is nice to feel comfortable in a group.”

In October 2019, David and his son were presented with an Eyres Monsell Volunteer Award by Councillor Karen Pickering, to recognise their contribution to Rolleston Green Gym. David has since expanded his voluntary activity, volunteering regularly at South Wigston food bank and becoming a key member of the Eyres Monsell Action Group. In 2020, he signed up as an NHS Volunteer Responder, where he delivers medication to people who are vulnerable and shielding.

Adur and Worthing, West Sussex: Growing Communities

In September 2015, 25 local green space and "Friends of…" groups were identified as working largely in isolation from each other in Adur and Worthing. A consultation exercise with these groups, the local councils and other local partners identified a need for mutual support and the potential for joint working.

TCV and Adur & Worthing Councils facilitated regular monthly meetings, where these groups shared their achievements and plans for the future. This provided a better understanding of groups’ capabilities and needs and enabled TCV and Adur & Worthing Councils to work with them to design extra support. A green space partnership, Green Tides, was developed and supported and became independently constituted in 2017.

The Growing Communities programme, delivered by TCV in partnership with Adur & Worthing Councils, has supported Green Tides to develop new local partnerships, expand its membership to over 40 groups, and build its resilience and sustainability.

Feedback from Green Tides includes:

“Support with funding applications has meant that funding has been obtained quickly and in a timely manner to grow and develop Green Tides, e.g. the website, branding, raised social media profile and insurance for groups.”

“Support with recruiting new committee [members] recently has increased capacity of the committee.”

“Doing events jointly with Growing Communities has made going to events achievable and Green Tides has been able to attend more events and raise their profile in the community through this.”

East London: Save Lea Marshes

https://sustainablehackney.org.uk/profile/SaveLeaMarshes https://www.saveleamarshes.org.uk/2019/09/26/help-make-lea-bridge-waterworks-a-wild-haven/

Save Lea Marshes began as the Save Leyton Marsh campaign and in 2013 expanded its remit to protect Leyton, Hackney and Walthamstow Marshes as open green spaces for future generations, regardless of income.

The vision for the Waterworks in East London involves re-connecting, restoring and rewilding much of historic Leyton Marshes for the benefit of people and wildlife. Part of the site is already a designated nature reserve, with the former Thames Water Depot on one side and the Waterworks Meadow on the other.

The campaign is crowdfunding for ecological surveys of the Waterworks Meadow to protect it from inappropriate commercial exploitation, such as a proposed music festival which was prevented through a vocal community campaign in 2020. The survey data will be used to persuade the Lee Valley Regional Park Authority to protect and enhance the habitat rather than use it as an events venue – rewilding the meadow for the benefit of wildlife and encouraging endangered birds, reptiles, insects and plants to return. The site, a former golf course, has already begun to regenerate naturally, and threatened birds and other species have been recorded there.

The campaign is also working with other community groups and CPRE London to protect the neighbouring Thames Water site from development, so that it can be opened up to public access and re-imagined as the East London Waterworks Park – a place for wild swimming and community horticulture, with the vital habitat along the river connecting up with the Middlesex Filter Beds Nature Reserve, while other parts of the site will be left to regenerate naturally.

The Waterworks Meadow and East London Waterworks Park will provide people with free or low-cost opportunities to improve their physical health by promoting walking, horticulture, and wild swimming. Reconnecting these areas will enable people to roam freely throughout the Lower Lea Valley, following long-distance walking routes.

This new vision for the historic Waterworks will increase biodiversity, support climate resilience, improve health outcomes and strengthen people’s access and connection with nature – all vital for the coming ecological challenges ahead.

“We’re really excited about our vision for the Waterworks. In times of ecological emergency this rewilding project could not only improve biodiversity, but create opportunities for people to better connect with nature, whilst at the same time enhancing climate resilience going into the future.” Caroline Day, organiser.

Appendix: The 50 priority council areas for investment

These are the council areas that need most investment because they have the greatest number of green space-deprived neighbourhoods, but all green space deprived areas should be addressed.

Note: a full list of council areas in England is in the full report (PDF).

Notes and references

An update to the earlier analysis was carried out in October to include small areas of green space (less than 2 hectares) previously excluded. One category of neighbourhoods was also moved from Rating E to Rating D. The resulting changes are overall not significant and the implications of the analysis remain the same – millions of people live is neighbourhoods deprived of green space, BAME people are more than twice as likely to live in one of these neighbourhoods than white people, and almost 40% of BAME people live in areas rated E. We continue to listen for ideas on how to further strengthen our analysis.

- 1Our analysis is not without weaknesses. We have used the ONS definition of what is public green space, which does not capture all green spaces for which there may be public access. For example, it excludes allotments some of which have public access. The dataset does not include wildlife sites, some of which may be open to the public, nor does it include beaches. The data also does not capture the quality of the green space, which is a major issue for people and wildlife. If a green space is perceived to be unsafe it will not be used. If it is kept as short grass, it will bring little or no biodiversity benefits. The data does not capture green infrastructure, such as street trees, planters, green roofs and parklets, all of which enhance the quality of an area and can provide important corridors for nature. Nor does it capture the extent to which local communities are engaged in shaping how local green space is managed, maintained and enhanced. The health benefits from a green space are more than its availability, but also how individuals can engage with it, alone or with others. Our rating system is necessarily subjective and alternative approaches are possible. We are making the full data set freely available and would welcome others using it to test alternative analytical approaches.

- 2The road to renewal: five priorities for health and care, The King’s Fund (2020). www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/covid-19-road-renewal-health-and-care

- 3Rt Hon Matt Hancock, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, address to the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Longevity. www.gov.uk/government/speeches/adding-years-to-life-and-life-to-years-our-plan-to-increase-healthy-longevity

- 4Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review) (2010). www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review

- 5Landscapes Review (2019). assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/833726/landscapes-review-final-report.pdf

- 6Landscapes Review of National Parks and AONBs, CPRE submission to Call for Evidence. luc.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=9e259557dbaa4bb7b6a6d4078332e996

- 7Charter for Open Spaces in England, Open Spaces Society (2020). www.oss.org.uk/charter-for-open-spaces-in-england/

- 8Green Space Index, Fields in Trust (2020). www.fieldsintrust.org/green-space-index

- 9Revaluing Parks and Green Spaces, Fields in Trust (2018). www.fieldsintrust.org/revaluing

- 10£5 million for social prescribing to tackle the impact of COVID-19, UK government (2020). www.gov.uk/government/news/5-million-for-social-prescribing-to-tackle-the-impact-of-covid-19

- 11Improving access to greenspace: A new review for 2020, Public Health England (2020). assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/904439/Improving_access_to_greenspace_2020_review.pdf

- 12Scoping UK Urban Natural Capital Account – Noise Extension, Final Report, Eftec (2018). randd.defra.gov.uk/Document.aspx?Document=14251_ScopingUKUrbanNaturalCapitalAccount-NosieExtension.pdf; UK Nature Capital Accounts: 2019, ONS (2019). www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/bulletins/uknaturalcapitalaccounts/2019

- 13UK Natural Capital Accounts: 2019, ONS (2019). www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/bulletins/uknaturalcapitalaccounts/2019

- 14Climate change, justice and vulnerability, Lindley et al., Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2011). www.jrf.org.uk/report/climate-change-justice-and-vulnerability

- 15UK parks boost quality of life by £34bn BBC (2018). www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-44027753

- 16Communities Secretary welcomes response to his call for parks to open, UK government, (2020). www.gov.uk/government/news/communities-secretary-welcomes-response-to-his-call-for-parks-to-open

- 17Updated indicators of climate change risk and adaptation action in England (ADAS), Committee on Climate Change (2017). www.theccc.org.uk/publication/updated-indicators-of-climate-change-risk-and-adaptation-action-in-england-adas/; Progress in preparing for climate change – 2019 Progress Report to Parliament, Committee on Climate Change (2019). www.theccc.org.uk/publication/progress-in-preparing-for-climate-change-2019-progress-report-to-parliament/

- 18Neighbourhoods are Middle Super Output Areas (MSOAs) used by the Office of National Statistics. They are of average size 7,200 people and there are 6,791 of these areas in England..

- 19Report, London Green Spaces Commission (2020). www.london.gov.uk/WHAT-WE-DO/environment/environment-publications/london-green-spaces-commission-report

- 20Censuswide survey of 2,079 UK adults, 13-20 October 2015, Fields in Trust (2015). www.fieldsintrust.org/Upload/file/research/Park-User-Survey.pdf

- 21Parks face threat of decline with severe consequences, Public Parks, House of Commons Communities and Local Government (CLG) Committee report (2017). old.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/communities-and-local-government-committee/news-parliament-2015/public-parks-report-16-17/

- 22The lowest quartile, which is less than 57 m2 per person in the neighbourhood, and an average of 29 m2. In comparison, a singles tennis court is 196 m2.

- 23Less than 9 m2 per person, which is less than the minimum recommended by the World Health Organisation

- 24More than 9 m2 per person, but less than 33 m2 which is the Fields in Trust recommended minimum

- 25The Charter for Parks (2018). parkscharter.org.uk/

- 26Levelling Up and Building Back Better Through Urban Green Infrastructure: An Investment Options Appraisal, National Trust (2020). www.greenkeeperuk.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Greenkeeper-Report-for-FPA-Greening-Programme-July-2020-2.pdf; National Trust urges Boris Johnson to spend £5.5billion on neglected parks and open spaces to make Britain greener, Daily Mail (2020). www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8490259/National-Trust-urges-Boris-Johnson-spend-5-5billion-open-spaces-make-Britain-greener.html

- 27Green Spaces for Good, Fields in Trust. www.fieldsintrust.org/protect

- 28Estimate with the report for the Natonal Trust and others by Vivid Economics and Barton Willmore, https://www.vivideconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Greenkeeper-Report-for-FPA-Greening-Programme-July-2020.pdf

- 29The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation is a relative measure of deprivation across 6,979 small areas in Scotland, known as data zones. Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) 2020 data taken from Inverclyde Health & Social Care Partnership Report No: IJB/34/2020/LL, 17 March 2020. www.inverclyde.gov.uk/meetings/documents/13198/05%20SIMD%202020.pdf