Mike Childs11 Jan 2022

Summary

As climate scientists have predicted the weather is becoming windier, wetter and wilder around the world and Northern Ireland is becoming more prone to extreme weather events. In the past decade we have seen more flooding, both in our cities and in the countryside, whether from intense rainfall, increased river flow or sea surges. Even with advance warning systems in place and improved flood defences, we need to become much more resilient to flooding and make use of the planning system and a broader suite of flood management tools to address risk.

Around 45,000 properties in Northern Ireland are currently at risk of flooding. But the effects are not felt equally. Flooding often has a worse impact on lower-income households who cannot afford to make their homes flood-resistant or the insurance premiums to cover flooding. And flooding can create mental challenges that can last for years in anyone who has suffered irreparable loss.

Natural flood management (NFM) is increasingly recognised as a vital tool for flood defence and almost always achieves multiple environmental benefits. But not enough emphasis has been placed on restoring nature as part of reducing flood risk, such as fully restoring peatlands and salt marshes, tree planting and increasing green spaces and water storage in urban areas and less hard surfacing to enhance drainage.

The Northern Ireland government needs to give this approach high priority. It must also support householders to be more resilient to flooding through grants for flood protection and affordable insurance schemes. Insurance companies should contribute to the costs, not least because making homes flood resistant is far cheaper than pay-outs for flood damage.

Is flooding getting worse?

Flooding causes misery and hardship everywhere. In many developing countries without the resources to build defences and where the weather can be more extreme, the impact can be devastating. For example, in 2020 over 2,000 people died in flooding in India and over 4 million were displaced. But even in Northern Ireland people have died because of extreme rainfall and the country is becoming more prone to surprise flooding events. Even with today’s better flood defences and advance warning systems, flooding still has a significant impact. For example:

- In August 2020 Storm Frances led to the rescue of elderly residents in Newcastle, County Down and others from Draperstown, County Londonderry.

- In August 2017, nearly two-thirds of the month’s average rain fell in just 8 or 9 hours in the north-west of Northern Ireland. Around 400 homes were flooded as were numerous businesses and significant areas of agricultural land. 89 bridges required remedial action because of the flooding, and the Glenrandal Bridge in Claudy collapsed.

- The winter of 2015/16 saw 4 major storms in rapid succession and resulted in the flooding of 174 homes, 36 commercial premises, and extensive agricultural areas.

- The English National Study of Flooding and Health found flooding significantly increases mental health problems, with anxiety and depression increasing 4-fold or more and lasting for more than 2 years.

The Climate Change Committee – the UK and Northern Ireland governments' official advisor – warn that the weather is getter wetter, windier and wilder.

Why is flooding getting worse?

The IPCC – the group of the world’s scientists that advises governments – says that humans have heated the planet at an unprecedented rate. As a result, sea levels have risen faster over the past 100 years than for at least 3,000 years and that the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events have increased. They say that with every increment of global heating, extreme weather events will get progressively worse and more frequent. This is because a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapour and release it in more intense downpours.

Over the past 40 years rainfall has been steadily increasing in the UK and it is now 7% more than it used to be. Sea levels have risen by 1.6cm. These changes don’t seem like much, but averages mask extremes. It is the intense rainfall events and storms in both summer and winter that cause most damage.

In the future we are likely to be facing even more dramatically extreme weather. Reduced arctic ice cover may lead to radical changes to the upper atmosphere's jet stream – which is a major influence on Northern Ireland’s weather. Global heating could lead to much greater sea level rise of 1-2 metres by 2100 as icecaps melt leading to significant loss of land to the sea and much greater levels of coastal flooding.

But additional flooding is not just a result of climate breakdown. We have also damaged Northern Ireland’s resilience to flooding by degrading the environment. By draining peat bogs, removing hedgerows, destroying salt marshes, concreting green spaces in urban areas and building on flood plains, we have undermined the ability of the natural environment to cope.

How many homes are at risk and who is most vulnerable?

According to the Northern Ireland Flood Risk Assessment 45,000 properties are at risk of flooding, of which 24,500 are at risk from surface water flooding and the remainder from river or coastal flooding. In theory, planning policy only allows for development in flood plains “by exception”. In practice, developments are still readily green-lighted in flood plains so this number will increase. Areas of Belfast are most at risk of flooding, followed by areas of Londonderry and Newry. The people most vulnerable to flooding are those with lowest incomes as they are less able to prepare for floods by adapting their homes, less able to respond to flooding events or to rebound as they are more likely to be uninsured. Elderly or disabled people are also vulnerable, as they are more likely to be trapped by flood waters.

Wherever it happens, flooding is a tragedy for families and communities. Even though most people survive all but the most extreme floods, property damage and the loss of irreplaceable personal effects such as photographs, keepsakes, furniture, and ornaments, let alone pets or farm animals, can cause mental suffering that can last for years.

Can nature restoration help?

Nature restoration can help protect land and properties from flooding and reduce but not eliminate the need for flood defences, like walls and barriers.

Natural flood management (NFM) is increasingly recognised as a vital tool for flood defence across the UK. For example:

- In Wales, Natural Resources Wales has worked with JBA Trust to publish maps to support the delivery of NFM, identifying potential locations for such measures in a catchment.

- In Scotland, a comprehensive handbook on how to deliver NFM has been published.

- In England, the Environment Agency in England provides numerous examples of NFM approaches in action.

In Northern Ireland, the 2021-2026 Flood Risk Management Plan (FRMP) gives greater emphasis to NFM with around a quarter of the expenditure proposed for "blue/green" infrastructure (£104 million out of £440 million). The Department for Infrastructure is also developing guidance on NFM. But despite this welcome investment, there are other significant opportunities for NFM that are not being funded..

Examples of NFM that need greater investment include:

Planting more trees – trees increase water drainage and hold back floods. Northern Ireland is one of Europe’s least wooded nations, with only around 9% woodland cover (119,000 hectares) with less tree cover than other parts of the UK. A report for the NI government by Forest Research found significant woodland creation opportunities for reducing flooding. It identified 249,300 hectares of priority areas for woodland planting to reduce downstream flood risk, comprising 172,100 hectares for wider woodland, 11,000 hectares for riparian woodland and 66,300 hectares for floodplain woodland. Despite this report the Flood Risk Management Plan says, “At this time there are no plans to take forward specific NFM woodland planting measures in NI … but it is possible that such measures could be developed within the timeframe of this FRMP”.

Restoring peatlands and soils –peatlands can act as giant sponges soaking up rainfall and releasing it slowly over time. But as the NI government acknowledge in its draft Peatland Strategy, most peatlands have been damaged, are in poor condition and will require more sustainable management and restoration. The strategy says that “By 2040, all high priority degraded peatlands will be under restoration management”. But the government makes no funding commitments in the strategy. The Flood Risk Management Plan also makes no commitment for funding peatland restoration.

Creating more water storage capacity - uplands and lowland floodplains can store the large volumes of water that come with storms. Well-managed floodplains can also be a haven for wildlife. This will only require losing very small amounts of agricultural land. Water can also be stored by creating more ponds and lakes. In urban areas rainwater from storms can be stored in water butts, including potential Wi-Fi enabled water butts that empty ahead of a storm to capture storm water.

Restoring the natural flow of rivers – many rivers have sections where they have been straightened and/or have had concreted riverbanks installed. This can speed the river flow and cause flooding downstream. Natural and restored riverbanks act as sponges by absorbing excess water and river meanders can store more water.

Increasing soak-away capacity – much of our urban areas have been concreted over. As surface water flooding is the greatest risk in many areas, it makes sense to prevent further hard surfacing and replace existing concrete with more porous materials where practicable.

Are the government's plans good enough?

The scale of floods in the future will be determined by government policies and actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to slow climate breakdown. In the UK as a whole, as in other parts of the world, there is a massive gap between pledges to reduce emissions and policies to do so. Northern Ireland does not yet have a climate change law, although Friends of the Earth Northern Ireland has played a leading role in campaigning for a strong law and at last the Assembly is currently considering one. The NI government does not have a comprehensive climate action plan and although it has targets in areas such as electricity grid decarbonisation, it needs plans for other sectors - such as how agriculture must change to help the UK meet international pledges to reduce methane emissions by 50% by 2030.

Northern Ireland must also be much more resilient to extreme weather events – flooding, extreme heat and high winds. This means spending money on flood defences (including NFM), and ensuring at-risk householders are prepared for flooding, can respond effectively and are able to rebound quickly.

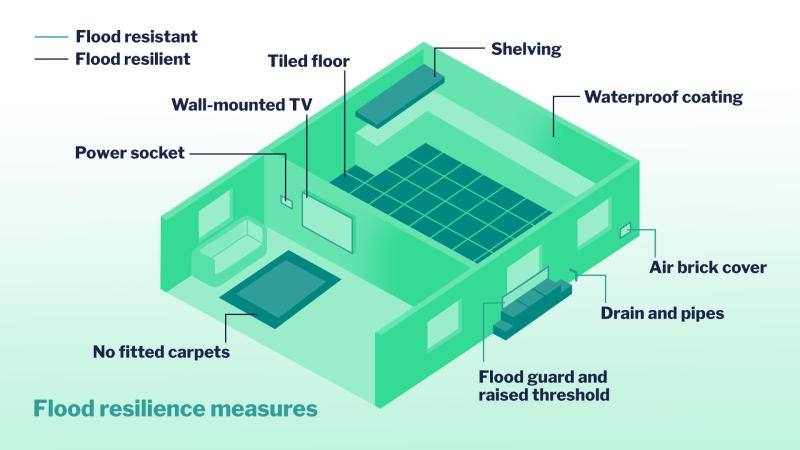

In reality poorer households are less able to invest in their properties to make them more flood resistant (by installing flood gates for example) and resilient (easier to clean and dry out). Some are less able to respond when flooding occurs if they are disabled or frail due to age or illness. And many are unable to bounce-back after floods. UK-wide figures suggest around 50% of all renters may not have home contents insurance and this rises to 61% of low-income renters.

The NI government is investing in flood defences. In its Flood Management Plan, published in December 2021, it has allocated £440 million over a 6-year period. With a population of 1.9 million this averages £38.60 per person per year. In Wales the expenditure is £20.82 and in England it is £17.85. These comparisons are only illustrative and should be treated with caution because a) expenditure needs to be related to risk, and b) some measures that will aid flood defence may be delivered by other budgets for other purposes (for example, England expenditure on peat restoration). But despite this expenditure, there is more the Northern Ireland government can do.

More grants for flood resistance and resilience

Friends of the Earth believes that more grants should be available for people living in high-risk flood areas to make their homes more flood resistant and resilient. The NI government has a pilot Homeowners Flood Protection Grant Scheme and an evaluation of the scheme has demonstrated it's needed. It has allocated £250,000 a year for this. The grant scheme provides 90% funding of works up to £10,000 to make a home more flood resistant or resilient. Although more generous than its equivalent in England, the need for the homeowner to fund 10% may restrict the ability of low-income homeowners to benefit from the scheme.

The insurance industry should also contribute to a UK-wide programme of making homes flood resistant and resilient, not least because prevention is much cheaper than the cost of flood damage recovery. On average insurers pay out £50,000 per property for flood damage, whereas the cost of basic flood resilience is around £4,000 and more complete flood resilience is around £12,000. The UK government says it is considering how the insurance industry can contribute through the Flood Re Scheme, which is legislated at a UK level (see below).

Landlords should also be required to install flood resistance and resilience measures for rental properties that are at high risk of flooding.

Better insurance cover

Cheaper house contents insurance is made available to low-income householders in flood prone areas through a scheme called Flood-Re. This UK-wide scheme raises a levy on all household insurance and uses this money to both partially subsidise insurance in areas at high risk of flooding and provides a pot of money for insurance company pay-outs after flood events. But insurance premiums are still more expensive for properties at risk of flooding than those not at risk. This can lead to lower income households in particular opting for home insurance that doesn’t cover flooding or for no insurance at all.

As recommended by the UK government-commissioned 2020 Blanc Review into flooding insurance, the government needs to make insurance more affordable for low-income householders in flood prone areas, particularly for low-income tenants and require landlords to have building insurance so they can rehouse tenants for a period if flooding occurs. The UK government has said it will not require lower insurance premiums but will look at other unnamed approaches for increasing insurance uptake.

A greater focus on nature in flood defence

So-called ‘hard flood defences’, such as flood defence walls, are needed to protect properties. But historically not enough emphasis has been placed on restoring nature as part of reducing flood risk, such as the full restoration of peatlands and salt marshes, tree planting, and increasing green spaces and water storage areas in urban areas, including removing hard surfacing to enhance drainage.

As explained above, the Flood Management Plan for Northern Ireland is not funding the scale of woodland creation for flood alleviation recommended to the government by Forest Research, nor is it funding peatland restoration goals. Spending on NFM to protect Belfast is welcome but the approach should be adopted across the country.

Flood defence spending is one part of the flood resistance and resilience story. Addressing the lack of permeable ground in urban areas is another. The Flood Management Plan has a strong focus on Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) which is necessary given that surface water flooding is currently the greater flood risk. This strategy for using SuDS in new developments is strong, but it is less clear how retrofitting existing urban settings will be addressed. Flood alleviation measures could include increased planting of street trees and converting areas of tarmac to parks, which would also bring benefits for mental health and nature.

What needs to happen?

The NI government has accepted more needs to be done. Friends of the Earth is calling for:

- The NI government should enable 100% grants for its Homeowners Flood Protection Grant Scheme for low-income homes. It should also make the grant available for homes at high-risk of flooding and not restrict it to those at risk of repeat flooding. The insurance industry should contribute to the costs of this programme through the Flood-Re Scheme. Landlords should be required to undertake flood resistance and resilience works in high-risk homes.

- The cost of contents insurance for low-income householders at high risk of flooding should be further reduced through the Flood-Re scheme. It should not be more expensive for them to insure their home than an equivalent home that is not flood prone (except where they refuse to fit fully funded flood resistance and resilience measures). This will require UK government action. These householders will have contributed least to climate breakdown which is increasingly responsible for the flood risks they face.

- The NI government should produce and fund a Natural Flood Management Plan that delivers the levels of tree planting recommended by Forest Research and on peat restoration goals. The plan also needs to identify how salt marshes and sea meadows can be restored given these are not only important flood defences but also vital habitats and carbon stores.