14 Jul 2020

Download the full report

This report identifies the policy changes needed for a green and fair recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Green because human health and wellbeing is dependent on a healthy planet. The impacts of climate change seen across the world are a vivid demonstration of this reality, but also, as the World Health Organisation says "our own destructive behaviour towards nature is endangering our own health – a stark reality we’ve been collectively ignoring for decades."

Fair because while we all suffer the consequences of a degraded world, not everyone suffers equally. For example, black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities suffer most from the lack of green space in our towns and cities and from worse air pollution. And globally it's poorer communities who suffer most from environmental degradation, despite having contributed least to these problems. Fairness is not, however, just a moral imperative – it's also a necessity for addressing shared global problems. We're all in this together, and we need to act like it.

The COVID-19 recovery plans that are being written are a great opportunity for change. As Arundhati Roy puts it so eloquently, "historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world."

We identify actions needed in 5 areas: health and wellbeing, green jobs, fixing the economy to work for people and the planet, international co-operation, and empowering communities and their elected local politicians to lead the recovery. Right now, there is an unprecedented breadth of people, organisations, and businesses calling for COVID-19 recovery plans to be green and fair. Now is our opportunity, we must not squander it.

1. Prioritise health and wellbeing

Human health and wellbeing is dependent on a healthy planet. The impacts of climate change seen across the world are a too often vivid demonstration of this reality. Destruction of habitats also impacts on human health. For example, the United Nations and World Health Organisation have highlighted that many diseases over recent years, including Sars and Ebola, originated from animal populations under conditions of severe environmental pressures. The same might be found to be true for COVID-19. They warn that "our own destructive behaviour towards nature is endangering our own health – a stark reality we’ve been collectively ignoring for decades."1 We need to fix the planet for our own health and wellbeing, as well as for the wellbeing of future generations.

While we all suffer the consequences of a degraded world, not everyone suffers equally. BAME communities suffer most from the lack of green space in our towns and cities, and they suffer worse air pollution. Poorer and marginalised communities are least able to prepare for the extreme weather caused by climate change and least able to respond and rebound when it occurs. Globally it is poorer communities, and particularly BAME people, who suffer the most from climate breakdown, air pollution and other forms of environmental degradation. The great injustice is that poorer people and marginalised communities have contributed least to these problems but are disproportionately harmed.

The respected Lancet Commission on Climate Change has said "left unabated, climate change will define the health profile of current and future generations, will challenge already overwhelmed health systems, and undermine progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and universal health coverage (UHC)."2 In other words, it's necessary to address the environmental causes of ill health, as well as properly invest in the health systems that we all rely on when we fall ill, a point made strongly by the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee.3

The UK’s COVID-19 Recovery Plan, as well as recovery plans developed by the UK’s nations and local authorities, are an opportunity to build back better by simultaneously rebuilding our economy while addressing the health threats that result from continued environmental degradation.

The UK has much lower levels of cycling than countries such as Denmark and the Netherlands. Increasing the proportion of journeys by bike is necessary to reduce carbon emissions. It is also necessary to reduce crowded public transport, traffic congestion, and air pollution as the public are told to avoid public transport to enable social distancing. As part of the COVID-19 Recovery Plan the UK government must commit to spending £2 billion a year on walking and cycling. This would bring us up to the level of investment in countries such as the Netherlands.4 As part of this it will be necessary to ensure that devolved nations also have the necessary resources to deliver the quality cycling infrastructure that is needed. A June 2020 poll found that in 5 of the UK’s major cities almost four-fifths of residents want cars to give way to bikes, buses and walking.5

The recent encouragement of local authorities to install temporary cycle lanes by the UK government and devolved nations is welcome. But COVID-19 Recovery Plans must go further and enable temporary changes to reallocate road space to pedestrians and cyclists to be made permanent.

Research for Friends of the Earth by Transport for Quality of Life has shown that the provision of segregated cycleways at the scale provided in countries such as Denmark, alongside widespread adoption of e-bikes, could result in a third of journeys being by bike.6 This would significantly benefit health and reduce climate change gases and air pollution. The Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions at the University of Leeds has even suggested that the use of e-bikes in rural as well as urban areas could halve carbon emissions from surface transport.7

Spending on cycling and walking is socially progressive as well. Almost 50% of low-income families don’t have access to a car, the proportion of women that don’t have access is double that of men, and BAME people are less likely to have access to a car than white people.8

There are at least 36,000 premature deaths in the UK annually because of air pollution (globally the figure is 5 million).9 Air pollution makes people more vulnerable to COVID-19.10

So far the government has been resisting putting a firm date for meeting the World Health Organisation (WHO) standards into law. This is despite the death toll and the widespread support to include this date in the Environment Bill, which is progressing through Parliament. The Welsh government is committed to a new Clean Air Act, including on WHO standards, with a White Paper due later this year. The Environment Bill should include a 2030 target as the latest date for air quality to meet WHO standards for tiny particulate air pollution (PM2.5) because of the risk to health, as should a Clean Air Act in Wales.

Meeting these air pollution targets will require a significant shift from car travel to public transport, cycling and walking. This is true even with a rapid shift to electric cars. Likewise meeting climate goals will also require such a shift. This means significantly increasing the availability, quality, and affordability of public transport, including buses and trams. The Government and devolved nations must set a target to double the proportion of people that travel by walking, cycling and public transport by 2030. Currently only around one-third of journeys are by walking, cycling or public transport.

Right now, public transport is suffering financially as the public are urged to avoid using it where possible. Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, and Transport for Quality of Life have previously argued that bus franchising plus changing the structure of the railway so that it is a single entity operating under public control is necessary to meeting climate goals.11 The COVID-19 pandemic makes this more necessary, as private companies are in effect being almost entirely bankrolled by the public purse. For example, the railway companies have already been provided with an additional £3.5 billion and are calling for substantial financial support for at least the next 18 months.12The UK COVID-19 Recovery Plan must set a pathway for rapid railway renationalisation and local authority bus franchising. In Wales, the government is supportive of bus franchising but need to fast-track the action necessary to make it happen. It should also include developing more innovative ticketing, such as part-time season tickets to support more frequent home working.

In addition, even before COVID-19 there was a need to substantially increase investment in public transport. The UK government COVID-19 Recovery Plan must invest at least £1.3 billion a year more on buses, £5.52 billion on rail, and at least £1 billion a year on new trams, and this should be in addition to the extra funds provided to compensate for falling passenger numbers. A fair share of this will need to be allocated to devolved nations.

Meeting air pollution goals will also require the implementation of Clean Air Zones in towns and cities where air pollution is high.13 These must be funded as part of COVID-19 Recovery Plans, and their introduction should not be delayed.

Lastly, the government is reportedly considering a scrappage scheme as part of the COVID-19 Recovery Plan. An international review of previous scrappage schemes suggests that schemes that do allow for the purchase of another car should be restricted to only pure electric and funded by increasing taxes on more polluting vehicles.14 The UK government scrappage scheme should go further by supporting a modal shift in preference to a new car purchase, including the purchase of a bike or e-bike and public transport tickets, in order to support the growth of the most sustainable forms of transport. Focussing more on sustainable travel is also more equitable, as in practice a scrappage scheme aimed at the purchase of new cars only really works well with those with spare capital or easy access to credit which in effect rules out those on lower incomes.

If it does include support for buying an electric car this needs to be additional to the sales the car industry already needs to make to comply with EU law. It must not support the purchase of hybrid vehicles or Euro 6 cars or vans.

Only around a third of the population have access to a public park or playing field of a reasonable size15 within a 5-minute walk, and deprived communities particularly suffer from a lack of quantity of green space within their areas, as has been witnessed during the COVID-19 lockdown. White people are nearly 4 times as likely as black people to have access to outdoor space at home, whether it be a private or shared garden, a patio, or a balcony.16 A new Friends of the Earth analysis has identified the 1,108 neighbourhoods in England that are most deprived of green space. Almost 40% of people of BAME backgrounds live in these neighbourhoods, compared to only 14% of white people.

Also, not everyone has equal access to trees in urban areas either, with poorer areas often having fewer trees and only wealthy urban areas have greater than 30% tree cover according to Forest Research.17 Forest Research has said that all urban areas should have a minimum 20% tree cover. Friends of the Earth is calling for UK tree cover to be doubled and for the minimum urban 20% tree cover target to be met, and COVID-19 Recovery Plans should work towards this.

Green space and connecting people to nature is key to improving mental and physical health, as illustrated through the growth in social prescribing by health professionals who allocate an amount of weekly exercise in a green space or involvement in a community gardening project. It is not just the quantity of green space that matters, it is also the quality. Public green space should be managed to be nature-rich (eg, pesticide-free) and attractive to use (for example, free of litter, dog waste, etc.). Green space also helps mitigate the impact of heat waves in urban areas.

Quality nature-rich green space, alongside other green infrastructure such as green corridors (eg, street trees) and blue (water) corridors, are essential for nature restoration and resilience. The highly respected Lawton Review identified the critical role for green networks within our cities and towns in addition to more space for wildlife in our countryside if the UK is to deliver on nature restoration.

The Environmental Audit Committee has recommended that the National Planning Policy Framework in England should be revised to include a public green space target on local authorities. The government has responded to this recommendation by saying that "once the Green Infrastructure framework [under development] has been published, Defra and MHCLG will work together to see how our commitments on GI can be incorporated into national planning guidance and policy."18

COVID-19 Recovery Plans and planning policy must require and enable local authorities to meet quantity and quality green space standards that enable healthy living and help restore nature. In some places this may be repurposing car parks or roads to parks and parklets.

The UK COVID-19 Recovery Plan must increase funding for national nature restoration, including £0.8 billion a year for habitat creation (including afforestation to move towards a target of doubling tree cover) and £2.6 billion a year on environmental land management to ensure public money paid to farmers is used for public goods as recommended by the Greener UK coalition.19

The COVID-19 recovery plan must lead to a reduction of health inequalities which have become more apparent during the crisis, including those that result from a degraded and polluted environment.

Strong environmental and health regulations are essential to protect citizens from harm and enhance their wellbeing. But regulations do not cover all threats to health and in any case, regulators may choose not to adequately monitor or enforce them for a range of reasons (eg, lack of resources or staff, other priorities, or political pressure). In some instances, the public does not have standing to take forward its own case to enforce regulations directly in the courts, and Judicial Review may not be a realistic option. The ability of citizens to protect their health would be significantly enhanced by enshrining in a law a new legal right to a healthy environment that they can enforce easily and effectively where damaging environmental decisions impact their health and wellbeing.

A report to the UN General Assembly in New York by the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, David R. Boyd, said 155 countries already have a legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfil the right to a healthy environment, including countries such as Portugal, Spain, France and Norway.20

Wales has taken a step in this direction with its Wellbeing of Future Generations Act which requires public bodies to set objectives with a view to maximising their contribution to achieving each of the wellbeing goals, including "a society in which people’s physical and mental wellbeing is maximised."21Although this is an important contribution to achieving sustainable development, a legally enforceable right to a Healthy Environment would significantly add to the legal certainty that is needed.

A new law should:

- Provide a clear, simply expressed, and understandable Right that would aid both the public in using the law to protect their health in the courts, and a strong standard applied by the judiciary when considering cases.

- Increase the requirement on public bodies and regulators to better consider the impacts of their decisions on the environment and how that interacts with the health of the public as covered by this right, including the more marginalised people whose voice is not always heard in decision-making – because the right is for everyone.

- Be a stepping stone towards more enabling regulations requiring others, such as companies, to also respect the Right to a Healthy Environment.

- Reduce health inequalities resulting from environmental harm as more people are more able to vindicate their right in the courts, and public bodies will adjust their behaviour to protect the right in the first place for fear of strong accountability.

The UK COVID-19 Recovery Plan should commit to introducing a new law to provide people with a Right to a Healthy Environment as one of the tools for eliminating health inequalities that result from a degraded and polluted environment.

2. Put green jobs and livelihoods at the heart of the recovery

The Bank of England has said that unemployment could double because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Around 8 million jobs have been temporarily saved by the government’s furloughing programme but many of those may be lost over the following year. There is a need to create new jobs but not in polluting activities that harm the environment and public health. Instead the jobs need to be created in industries that protect and restore the environment or improve wellbeing in other ways.

There are already several reports that estimate how many jobs could be created through investing in the green economy through COVID-19 recovery plans. Estimates of job numbers vary in these because of different methodologies or boundaries of what jobs are and are not included in the studies, but they all point towards significant job creation opportunities if investment is prioritised to the green economy.

For example:

- Industry group Energy UK has said that there is an opportunity to create "mass employment across the entire country" from programmes including a housing infrastructure upgrade programme (including energy efficiency and eco-heating), accelerating the development of low carbon industrial clusters, and accelerating the transition to low carbon transport.22

- The Local Government Association says nearly 700,000 direct jobs could be created in England's low-carbon and renewable energy economy by 2030, rising to more than 1.18 million by 2050.23

- The Energy Efficiency Infrastructure Group says that 40,000 jobs could be created by the government in insulation over the next two years, and 150,000 by 2030.24

- Vivid Economics, in a report for WWF, has identified that a transition to net zero will lead to more than 200,000 new jobs.25

- The IPPR Environmental Justice Commission cited research suggesting 70,000 jobs could be created in offshore wind by 2023 and 81,000 in heat networks by 2030.26

The potential for growing green jobs is clearly huge, if policies are put in place to deliver them.

The UK has a notoriously old and leaky housing stock, and more than 2.5 million households in the UK are in fuel poverty. The sad reality is that this number will increase substantially if the coronavirus pandemic extends into the autumn and winter. Investment in energy efficiency has collapsed over recent years because of funding cuts.

In addition, to meet climate change targets, it is necessary to start replacing the gas heating and cooking in the UK’s homes with eco-heating options such as heat pumps. Under the current government proposals, it would take 1,500 years to fit the necessary number of heat pumps.27

The UK government and devolved nations should use COVID-19 Recovery Plans to bring all homes up to a decent energy efficient standard by 2030 (at least EPC C standard) and collectively install an average of 1 million heat pumps per year. This will create jobs across the UK, including in areas of high unemployment and those where the economic impact of COVID-19 has been greatest.

The Energy Efficiency Infrastructure Group have called for an additional public investment into energy efficiency for the next two years to create 40,000 new jobs, in addition to the financial pledges made by the government in the Conservative Party Manifesto.28 Its estimate of the new investment needed for energy efficiency is comparable with that made by Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, E3G and others in 2019.29 In our report we identified that around £5.4 billion was needed each year for insulation and installing low carbon heating options such as heat pumps. In total, over the next two years COVID-19 Recovery Plans should invest at least £10.5 billion into energy efficiency and heating. Additional government and devolved nation investment in this area will also encourage private investment across the UK.

But spending is not all that is required as regulation is also necessary, including:

- In the private rented sector standards need increasing. The UK government must, as part of the COVID-19 Recovery Plan, set mandatory energy efficiency targets for homes in the private-rented sector to be energy efficient (EPC C level) by 2030 at the latest, with interim legally binding milestones. This measure will particularly help those on low incomes, such as many of the key workers active during lockdown, as well as young people. The Scottish government has already committed to introducing regulations to achieve this.

- In addition, also as being planned in Scotland, there should be measures to require energy efficiency improvements in owner-occupied homes at times of major refurbishment or sale. The UK government should follow the lead of the Scottish government and set energy efficiency standards that owner-occupied homes should meet.

The regulation of energy efficiency in homes is not devolved to Wales as it is in Scotland and Northern Ireland, although Friends of the Earth argues it should be.

The government has set an ambition for 40GW of offshore wind by 2030, which will create tens of thousands of new jobs, particularly in areas which have suffered job losses due to the decline of industries such as shipbuilding and steel. This is very welcome. They have also said that onshore wind and solar can now compete for their Contracts-for-Difference (CfD) support scheme, which guarantees a price for the electricity produced and gives investor confidence. However, they also limit the amount that can be built using this support mechanism. But in England they have in place a brake on onshore wind development through a de facto ban that in effect allows a minority of people in a community to block a new onshore windfarm development even if it has been supported by the majority of the community. The UK government must remove the de facto ban on onshore wind in England in its COVID-19 Recovery Plan and remove the cap that limits the amount of new renewable energy capacity supported through CfD auctions. Doing so will significantly increase job opportunities in this sector.

The government’s ambitions for renewable power also need to substantially increase. Last year saw the smallest increase in renewable energy capacity for more than a decade with only 3GW of plant built.30 The UK should be aiming to build 14GW of additional capacity every year. This is greater than the 9GW the Committee on Climate Change says, as a faster and deeper reduction in greenhouse gas emissions is needed than it has recommended.31

The UK Government and nations must collectively aim for 14GW of new renewable energy capacity year on year. The majority of this should be wind power as this generates more power in the winter when renewable power will be needed for heating.

COVID-19 will lead to increased unemployment across the UK, but some areas and some sections of society will be harder hit than others. The RSA found "a stark geographical divide, with rural areas located in the north and south west of England most at risk of high job losses" and that "younger workers are overwhelmingly more likely to be furloughed – nearly twice as likely as middle-aged workers."32

The Social Market Foundation (SMF) has said that to protect those who lose their jobs as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic from the "scarring effects" of unemployment, the government should draw up a new work-and-training guarantee programme so that anyone who cannot find a job can be paid by the state to carry out a green job.33 The Trades Union Congress (TUC) has similarly argued for a jobs guarantee, in addition to other measures to prevent job losses.34

Young people are particularly vulnerable to job losses because of the pandemic35 and it is feared that the pandemic will have serious long-term consequences for their mental health.36 The scheme promoted by both the SMF and TUC highlights the importance of this guarantee for young people. Both also highlight the importance of using the scheme to help deliver climate emissions reduction goals.

The TUC proposal is that jobs created through a work-and-training guarantee pay at least the National Living Wage (or union negotiated rate for the job). The jobs could be with the private or public sector but must include accredited training with participants spending at least 20% of their working week for training and education. It envisages that jobs through the scheme are guaranteed for young people under the age of 25 after 3 months of unemployment and for the over 25s after 6 months. Robert Halfon MP, Chair of the Education Select Committee, has also argued for guaranteed apprenticeship for young people.37

The UK government should work with the nations to introduce a jobs guarantee scheme for those made unemployed due to COVID-19, with the central aim of skilling-up people to work in the green economy.

In any case, a much greater focus is needed on training regardless of the COVID-19 crisis because society, technology and economies are rapidly changing anyway. According to NESTA 6 million people in the UK are in roles that are likely to radically change or entirely disappear due to automation, population aging, urbanisation, and the rise of the green economy.38 A dystopian view of this is high levels of unemployment and people trapped in insecure, low value, low pay employment. But NESTA also says that "evidence shows which skills people will need in the coming years as jobs change, and new, tech-based training and careers solutions are becoming available for people who want to reskill so they are ready for the future."

Several local authority organisations, together with green groups including Friends of the Earth, have also called for a greater focus on skills and training, including better use of existing resources.39 The UK COVID-19 Recovery plan must enable councils to accelerate low carbon skills development by joining up the National Skills Fund, the National Retraining Scheme and the Apprenticeship Levy at local level and align this with place-based employment and business support systems. The devolved nations' COVID-19 recovery plans similarly need to give high priority for accelerating and simplifying training programmes.

The Association of Colleges, Students Organising for Sustainability, and University and Colleage Union have called for £500m of new money to be allocated to colleges over this parliament, frontloaded to the 2021/22 academic year for the development and delivery of low-carbon vocational training and reskilling. £100m of this should be used to establish a new network of National Centres of

Excellence in Low Carbon Skills at a number of further education colleges they say, each focusing on different

aspects of the low carbon skills gap.

But training for the future also needs to start earlier than young people entering colleges or the world of employment. A 2019 OECD study said "...the UK has the highest level of prevalence of memorisation in classrooms, which has also been shown to reduce a child’s ability to solve problems and think critically." It says that countries like Japan and China that used to depend on rote learning have shifted to a much greater emphasis on understanding and critical thinking. The report says that “The dilemma for educators is that routine academic knowledge (the skills that are easiest to teach and easiest to test) are exactly the skills that are also easiest to digitise."40 In other words, teaching needs to be transformed to help develop the critical thinking skills young people need, including in a context of a changing environment.41 The Durham Commission on Creativity and Education makes important recommendations that all education authorities and establishments should consider, as well as devolved nations and the UK government.42

Some industries do not have a future in a low carbon economy (for example, fossil fuel extraction) and the transition of workers from these industries needs to be planned. The social damage caused by the unthinking and uncaring transition from coal mining are still evident decades on. Instead a planned transition is needed. This will need funding.

Friends of the Earth Scotland has been working closely with unions and others on what a transition needs to look like.43Scotland is home to much of the UK’s oil and gas workforce. Even in Scotland there will be a net gain in jobs created through the transition to the green economy but as elsewhere it is necessary to target support, training, and investment to areas most in need. Friends of the Earth Scotland’s research with Oil Change International and Platform shows that given the right policies, clean industries could create more than three jobs for every North Sea oil job at risk, and can enable an "equivalent job guarantee" for every oil worker.44

Not all those working in currently polluting industries will need to change job because some industries can clean up. For example, the car industry is a major employer in the UK and in some areas the main employer. It is widely recognised that even with a significant shift to public transport, cycling and walking there will still be many cars on the road, and that these need to be electric. Electric vehicles are the future and to protect jobs the UK needs to be at the forefront of the transition. The government needs to support and encourage this transition, including through setting an early date to ban the sale of new petrol or diesel cars and vans. The UK government’s COVID-19 Recovery Plan should say that after 2030 only pure electric new cars and vans can be sold.

Steel, cement, and other industries are major users of fossil fuels, yet the use of hydrogen manufactured from water and renewable energy or electrification can wean these companies off fossil fuels.45

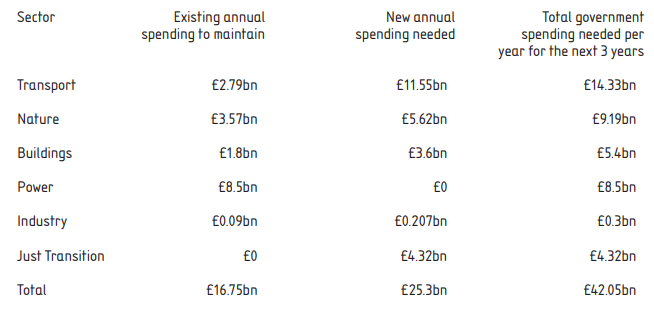

The IPPR Environmental Justice Commission has mapped those areas where the highest proportion of jobs are in industries that are greenhouse-gas related.46 This kind of mapping allows for a targeted response to enable a planned transition. The UK government should fund the transition with £4.32 billion each year and work with devolved nations, councils, unions, and employers to develop locally relevant transition plans to fund skills development, retraining, and for local investment to develop new employment within the areas.

3. Fix the broken economy so that it works for all people and planet

The UK economy has been badly damaged by the pandemic. But it is not as though it was working brilliantly before.

UK economic strategy, like many others, was fixated on growth (GDP) and rising consumption even though the result has been severe damage to the environment, and the endangering of the prospects of future generations. The economy has also seen a flourishing of low paid jobs in the gig economy. The gap in household wealth between richer and poorer families has also grown considerably since 2006 according to the Resolution Foundation, driven to a large extent by house prices and rising values of financial assets.47 Wealth provides economic resilience for times of hardship, for example a period of unemployment or to rebound from a flooding event, and it is also positively correlated with wellbeing. Wealth inequalities impact on social mobility.

But it does not have to be like this. Out of the ashes of the economic ruins from the pandemic an economy that works for people and the planet can be born. It’s just necessary to break the fixation with GDP and instead point economic strategy in the direction of increasing wellbeing and restoring the environment.

Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, WWF, and others identified before the COVID-19 pandemic the level of government spending needed to begin the process of rapidly reducing greenhouse gases, restoring nature, and stepping-up support for developing countries.48 The sum of money, £42 billion per year for the next three years (see table below), is small change compared to total government spending, and is dwarfed by the scale of the cost to the UK economy of protecting lives from COVID-19. It will also be less costly than the damage to lives, livelihoods and economies from not taking sufficient action on climate change.

The money for environmental spending can be raised by several means. One method is reducing spending on harmful activities. For example:

- The government has said it will spend £27 billion on roads in its Road Investment Strategy 2. It says this is the largest roads building programme ever. This is in addition to the £3.5 billion for schemes on local authority roads. The grassroots campaigning organisation Transport Action Network, which is taking the government to court over this programme, has said it has uncovered "secret plans to spend £90 billion over the next 15 years and that’s just on the strategic roads network."49

- The HS2 railway is now estimated to cost over £100 billion.50 It will damage important wildlife habitats and will not reduce carbon emissions.51There is a strong strategic case to be made for an additional conventional north-south railway line but it could be done much more cheaply and with much less damage by not being high speed. And in any case the money would have much greater carbon benefits and social utility if it were spent instead on buses, trams, and cycling infrastructure.

The UK government should announce within its COVID-19 recovery package that it is scrapping its Roads Investment Strategy and HS2 to use the funds to deliver projects that will create jobs in the green economy, from housing retrofits to low carbon transport to nature restoration (including in towns and cities).

Other methods for raising money are through taxing harmful activities. For example:

- The UK fossil fuel industry causes at least £44 billion worth of environmental and societal damage each year but the tax paid is minuscule in comparison.52 A carbon tax, delivered through a range of measures for different sectors, could raise £20 billion a year until the 2030s, according to the Grantham Research Institute for Climate Change and the Environment.53

- The oil and gas industries have had taxes reduced over the years, to the extent that in 2016-17 they paid no tax. In addition, tax relief on decommissioning oil and gas rigs is expected to cost the UK government £24 billion over the next 20 years or so according to the National Audit Office, although it also said that these costs are highly uncertain.54 At least some of this tax relief could be reversed.

- Transport, particularly high carbon transport, could be taxed more. A Frequent Flyer levy or Air Miles Levy would increase costs for the small proportion of the population that take multiple flights each year. Reinstating the fuel duty with a 1% above-inflation rise in fuel duty each year for the next five years would raise about an extra £280 million in the first year, rising to £1.4 billion in the fifth year.55 A modest eco-levy (road-user charging) would raise enough money to halve the cost of all rail trips or provide free buses in towns and cities.56

The UK government is expected to announce some tax changes as part of its COVID-19 Recovery Plan. It should announce new carbon taxes such as those recommended by the Grantham Institute, including a Frequent Flyer Levy and road user charging in the form of an eco-levy. The revenue from new pollution taxes should be used in the first instance to fund green measures but any excess funds could be used to reduce employers' National Insurance contributions to reduce the cost of hiring staff and/or reducing taxes that disproportionately impact lower income households.

The issue of government bailouts for polluting industries has sparked controversy, particularly when it involves companies with billionaire bosses who haven’t paid taxes in the UK for over a decade.57 Friends of the Earth is supportive of measures that help workers in these industries, such as the furlough scheme or any retraining schemes that are delivered, but not in support of simply providing the businesses with large amounts of money to continue with business as usual when the COVID-19 crisis recedes.58

The Bank of England has provided £1.8 billion to the aviation industry with no environmental conditions attached. Environmental NGOs, including Friends of the Earth, have spelt out how the aviation industry needs to operate post-COVID-19.59 This involves including the emissions from the sector within the UK carbon accounting regime for greenhouse gas reductions (carbon budgets), ensuring the industry is properly taxed, and a requirement on technological innovation to further reduce emissions. Bailouts need to be accompanied by strings which dictate how the industry must operate in the future. The aviation industry in particular has had a largely free ride when it comes to environmental impacts for decades, and this needs to stop.

The issue of bailouts to oil and gas industries was discussed by the recent Parliament’s Citizens’ Assembly, the interim findings of which have just been published.60 The Assembly consisted of 108 people who were selected to represent the demographics of the UK population and the levels of concern about climate change. 79% of participants thought government support to enable recovery from COVID-19 should be designed to help achieve net zero. Statements made included "I don’t think oil or gas companies should be given bailouts, you’re wanting to stop them anyway, so why support them – support the people who work for them but not the companies – that’s because they aren’t compatible with net zero" and "avoiding lock in of fossil fuel use [is] key – best chance to do this is now to avoid going back into the trap of fossil fuels again. That would be disappointing." These sentiments reflect Friends of the Earth’s position, that any bailouts must include conditions that transition the industry towards a low carbon future and this must include that the industry pay the levels of tax which reflect the damage its products do to people and the environment.

Any COVID-19 Recovery Plans that include bailouts for fossil-fuel industries must have conditions attached so that the companies involved are swiftly reducing emissions from their operations and use of their products so that a rapid transition to net zero is achieved.

As identified earlier, GDP is a poor measure of success because it can increase while the environment is harmed and wellbeing decreases. Instead indicators that measure real wellbeing are needed, ones which capture the value of unpaid work (often by women), don’t discount environmental harm, and recognise the damage that income and wealth inequalities do for social cohesion, social mobility, and the willingness to pursue shared goals.

The New Zealand government has given up on using GDP as the measure of success. Instead it is using a Living Standards Framework, which is a composite of 12 domains of wellbeing,61 which was developed by the New Zealand Treasury.

Businesses,62 the Committee on Climate Change,63 local authority organisations64 and many others have said that the government’s COVID-19 Recovery Plan must deliver on the UK’s net zero ambitions. The government itself has said that its recovery plan will be green and fair. Despite this, there is still a risk that the metric used by the government and by the media to judge the success of recovery plans is GDP. The UK government, devolved nations, and local authorities should explicitly identify that the metrics to judge success of the COVID-19 Recovery Plans are how well they reduce poverty, decrease inequalities, meet carbon reduction and nature restoration goals, and contribute to the global delivery of the Sustainable Development Goals and not GDP.

4. Co-operate globally and act responsibly

At the time of writing the numbers of people affected by the COVID-19 pandemic are rising sharply in countries such as India and Brazil. As one of the world’s wealthier countries the UK has a moral responsibility to help poorer countries through this crisis.

But in the case of climate change the UK has more than a moral responsibility. Through the United Nations international climate agreement, it has committed to the principle of "common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities." This basically means that the UK must do more than developing countries to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

A year ago, the UK set a net zero date for territorial emissions by 2050. However, it has not yet set new interim steps along the path to this. To be consistent with its international obligations, the new pathway will need to result in less than half the emissions than the current pathway.65The Committee on Climate Change will advise the government on the new pathway at the end of this year.

It has also pledged, alongside other developed countries, to together provide $100 billion annually for a five-year period from 2020. The UK has said it will give £11.6 billion over the next five years, between 2021/22 and 2025/26.66

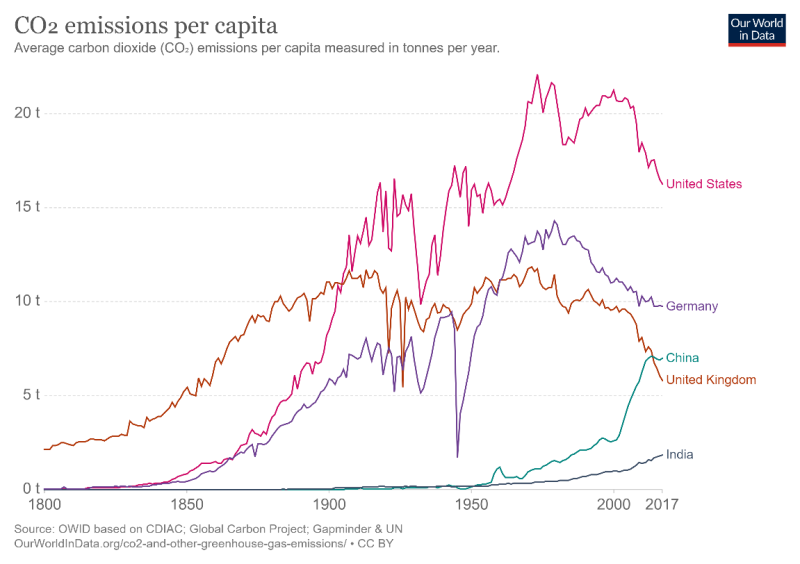

However, how much the UK should do is strongly contested. The UK is historically one of the largest contributors to climate change (see graph below), which is disproportionately impacting on poorer countries who are least responsible. Friends of the Earth and others believe the UK should do much more than it has currently pledged in terms of emissions reductions and finance.

The UK also has international commitments on nature through the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The UK will miss most of its 2020 biodiversity targets agreed at the Aichi meeting of the CBD, according to the advisor for the UK government and devolved administrations on UK-wide and international nature conservation.67 As with climate change, the UK also contributes significantly to impacts overseas through its consumption. A recent RSPB and WWF report on the impact of UK imports of seven commodities revealed that "the data shows nearly a third (28%) of the UK’s total overseas land footprint is still linked to countries assessed to be at high or very high risk of deforestation, destruction of other natural ecosystems and human rights abuses" and that "the study also finds the majority of all palm oil (89%), soy (65%) and cocoa (63%) imported to the UK comes from countries with high deforestation rates – and therefore there is a risk that these are associated with the destruction of biodiversity hotspots such as the Amazon, and forests in Indonesia and West Africa – home to endangered species including the giant anteater, orangutan and the pygmy hippopotamus, respectively."68

The UK’s global responsibility needs to extend well beyond what the UK does on UK-based carbon emissions and biodiversity. It also needs to reduce our impacts overseas and to improve on how we help developing countries grow out of poverty sustainably. If wealthy countries don’t do more, the global Sustainable Development goals will not be met and nor will agreed climate and biodiversity targets. The COVID-19 recovery plans need to be measured on how well they contribute to these goals, as well as how well they deliver domestically within the UK.

As identified above, the UK is committed to provide climate finance to support developing countries. The sums currently pledged equate to just over £2 billion a year for 5 years. But this is far from adequate.

Calculating a fair contribution of climate finance to developing countries by the UK depends on a range of factors, including how much historical pollution is considered, how much global emissions need to be reduced by to have confidence that the worst of climate change can be avoided, and how in practice you estimate how much finance is needed. For the latter – a financial estimate – different approaches can include estimates of the money needed by developing countries, putting a price on a tonne of carbon, estimating damage or variations of these. These complexities can lead to very different estimates. An estimate of financial flows based on damage would lead to very significant finance flow. For example, the International Monetary Fund has calculated the hidden costs associated with continuing to burn oil, coal and gas — such as air pollution and global warming — could have amounted to $5.2 trillion in 2017 alone, and much of this damage will be in developing countries.69

But what's clear is that current pledges are far from sufficient. Ottmar Edenhofer, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, and a former co-chair of the IPCC’s working group on mitigation of climate change, has said "neither the amount of financial flows nor their direction is sufficient to keep temperatures below 2 °C, let alone 1.5°C."70

A report for Friends of the Earth International and others estimates that the UK should support developing countries with £40 billion a year by 2025 and over $50 billion by 2030, taking into account the UK’s historical emissions and using a price of carbon at $65 per tonne, alongside reducing the UK’s own emissions by around 80% by 2030.71 This is in addition to existing development aid money.

Regardless of the methodology for calculating the UK’s international climate finance obligations, the UK needs to increase its contribution by at least tenfold.

Given that COVID-19 will significantly damage many developing countries' own resources for climate mitigation, it's essential that the UK’s COVID-19 Recovery Plan significantly increases UK international climate finance to our fair share, which is probably at least an order of magnitude increase on current levels.

Remarkably the UK not only continues to fund fossil-fuel expansion overseas but has increased funding since it signed the Paris Agreement on climate change.72 This is despite the Paris Agreement requiring "finance flows [to be] consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development."

Together with CAFOD and Global Witness, Friends of the Earth has highlighted how a little-known government agency (UK Export Finance) has supported offshore oil and gas fields in Ghana, expansions of oil refineries in Kuwait, and offshore oil platforms in Brazil, amongst others. 73 Other parts of government have also funded fossil-fuel extraction overseas.

Friends of the Earth is not alone in expressing concern about this funding, for example:

- The Committee on Climate Change has concluded that the UK’s export finance is not aligned with our climate goals.74

- The House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee has recommended that UKEF should stop support for fossil fuel projects by 2021.75

However, the UK government has failed to date to take any positive action in response to these calls. In fact, it continues to consider support for projects such as Mozambique Liquefied Natural Gas. This is despite the hugely detrimental impact on local communities, including human rights issues, arising from the existing LNG development and actions taken in connection with it. Such impacts are reported to include the forced removal of people from their homes and away from the land they depend on for their livelihoods, and violent attacks including fatalities.

COVID-19 gives the UK an opportunity to re-evaluate how it helps developing countries that are facing the triple emergency of climate, nature, and poverty as well as now COVID-19. Its spending shouldn’t make any of these crises worse. A good place to start would be for the UK COVID-19 Recovery Plan to commit to stopping all funding of fossil fuels overseas.

The UK has left the EU. This threatens our environmental standards and safeguards. Friends of the Earth and others are campaigning to make sure these rules keep working properly in the future. The government must guarantee environmental standards, establish a strong UK environmental watchdog, and enshrine principles such as the precautionary approach in UK law. They must do this before the end of the transition period.

But these legal protections are already under threat. The government is rushing to strike new trade deals, and the economic impact of COVID-19 has been used to justify starting multiple negotiations, including with the USA. These rushed trade deals could lead to seeing food on our shelves made using chemicals that are currently banned, or pumped full of unnecessary, harmful antibiotics. They could also mean giving foreign investors the power to influence our environmental standards. In a number of pieces of legislation currently before Parliament, the government must say no to any trade deal that weakens environmental, safety or consumer standards. And it must take the time to develop a world-leading trade policy which puts our environmental ambition at its heart.

5. Empower communities to lead the recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the willingness of people to reach out and help others in their community. It has also showcased the incredibly important role of councils and those that work within them, including Metro-Mayors. This is also true of the governments in Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. The UK government is indebted to these people.

Addressing recovery from COVID-19 and tackling the climate and nature crises will also require local leadership – from nations, Metro Mayors, City Regions, councils, and local communities – alongside UK government action. It simply isn’t possible to do so without further empowering local government, particularly given that recovery in each area will need to be different and tailor-made based on a deep understanding of the place, its history and its culture. Many councils across the area are now in significant financial trouble due to the extra expenditure on COVID-19 and falling revenues, so national government must make sure the necessary financial resources are made available to local government.

In addition to empowering and financially supporting nations, Metro Mayors, and councils, it will be necessary to empower those whose voice is not so easily heard in decision-making, for example young people and marginalised communities, as well as ensure participatory forums for discussing contentious issues are formed.

Over the last year Friends of the Earth has been working with local authority associations and others to identify the powers and resources councils need to deliver on climate change and nature restoration. This work has involved the input from scores of local authority staff and politicians from across the country and has been updated for the COVID-19 recovery. "The blueprint for accelerating climate action and a green recovery at the local level" identifies more than 50 policy changes that are needed in areas from nature restoration, to transport, to waste and sustainable consumption.76 It has 5 main recommendations, which are:

- Create a joined-up, multi-billion-pound, place-based clean infrastructure fund to enable local authorities to develop low-carbon and climate-resilient infrastructure.

- Join up the National Skills Fund, the National Retraining Scheme and the Apprenticeship Levy at local level to support reskilling, retraining and research for a net-zero well-adapted economy.

- Establish a programme to retrofit the UK’s building stock with energy and water efficiency and low carbon heating, as one of our national infrastructure investment priorities.

- Enable local authorities to significantly increase home working, cycling and walking provision – they have a special role to play in recovery from coronavirus, and will continue to play an important role in decarbonising transport.

- Speed up delivery of the £800 million Nature for Climate Fund to restore nature for all and enable community health and wellbeing through accelerating tree planting and peatland restoration. Support green spaces and other green infrastructure by properly funding local authorities to manage parks, open spaces, and public rights of way.

The Blueprint did not estimate the total financial resources needed by each local authority, because this requires a bottom-up and detailed approach. Also, not all investments would necessarily flow through local authority coffers, for example capital grants for heat pumps might flow directly to householders but local authorities would have an important role in coordinating an area by area approach to energy efficiency and heating. Nevertheless, it is clear that substantial investment is needed to reduce emissions and restore nature (£42 billion a year, see above) and some of that would be needed directly by councils (for example, for investment in trams or segregated cycleways). Camden Council has estimated its most ambitious plan to cut emissions by 68% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels would require an additional £900 million invested in its area, 77 whereas Bristol City Council has said £3 billion needs investing in the area on low carbon heating.78

Delivery on climate and nature goals requires the full and active involvement of government at all levels. The UK COVID-19 Recovery Plan must provide nations and councils with the significant new powers and resources they need to deliver an inclusive and green recovery in their area.

Those most impacted by environmental harm are often the poorest and most marginalised in society. The health impacts of the COVID-19 crisis has also shone a light on these inequalities. It is critical that those in power at all levels listen to those worse impacted. We have some mechanisms and laws that are a positive contribution to achieving this aim, but they are far from enough.

The UK government has recognised the importance of public participation in decision-making through ratifying the United Nations Aarhus Convention. This important but under-publicised treaty gives citizens rights to access information, public participation in decision-making and access to justice in environmental matters. Kofi Annan, former UN General Secretary, described it as "the most ambitious venture in environmental democracy undertaken under the auspices of the United Nations." However, while it covers decisions such as planning rules, it's not comprehensive and doesn't cover all the environmental decisions that will be made on the COVID-19 recovery. What’s more, it's poorly implemented in the UK.

There are regulators such as the Equality and Human Rights Commission, and the to be established Office of Environmental Protection (currently being legislated for in the Environmental Bill), but their responsibilities are to ensure existing laws are adhered to.

In Wales, the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act has created a Future Generations Commissioner who has set championing public participation and involvement in decision-making as one of her priorities. The Act itself identifies 5 ways in which public bodies must act, including "the importance of involving people with an interest in achieving the wellbeing goals, and ensuring that those people reflect the diversity of the area which the body serves."79 But the Act doesn't guarantee that the voice of those most impacted by environment is heard in practice, including in the development of the Welsh COVID-19 Recovery Plan, so there's still a need to keep the pressure on decision-makers to do so. That said, the Welsh Wellbeing of Future Generations Act is very important and welcome and has inspired the introduction of a Future Generations Bill into the UK Parliament, which the government should support.80

These important regulators need the powers, funding, and independence to ensure they can hold the powerful to account and act to protect the most marginalised in society. But ensuring the voice of the most impacted and marginalised is heard in all decision-making will need more than this, it will also require:

- The Aarhus Convention to be fully implemented into UK law, and its rights and visionary democratic principles used as a template for greater public participation.

- Public participation in planning decisions and the creation of local plans to be defended and enhanced rather than weakened, as is rumoured.

It will also require regulators such as the Equality and Human Rights Commission (and the Office for Environmental Protection when eventually set up) to take tough action to ensure that COVID-19 Recovery Plans do not unlawfully discriminate, for example by rigorously policing the public sector equality duty and protecting the Human Rights Act from political attacks. It will also require them to warn the government against creating worse environmental problems for the future (eg removing environmental protections and building across much needed natural spaces). This action by the regulators is not a substitute for proper participation but is complementary and will help to lessen inequality.

COVID-19 Recovery Plans should be developed in line with the rights and visionary democratic principles of the Aarhus Convention, and the processes used should be documented and available for public scrutiny. The UK should also begin the process of fully implementing the Aarhus Convention in a new Aarhus Act.

Participatory processes such as citizens’ juries and citizens’ assemblies can facilitate better decision-making and there are now several examples of local Climate Assemblies at different stages, inspired by the Extinction Rebellion movement. My Society has published digital tools for these approaches.81Being demographically representative these should amplify the voices of those so often shut out of political decision making. While it's not easy to ensure full participation in discussions and debates, it can be achieved. The example of Preston is strong.82 A city facing extraordinary challenges and hit by austerity has pioneered its own model of urban renewal and participatory community wealth building over the past decade to be named the most rapidly improving urban area in the UK to live and work.

But often plans and policies are driven by politics and the need to win votes to gain power. Young people’s voices need to be heard as COVID-19 recovery plans are drawn up, particularly given they will live with the environmental consequences for longer. Allowing younger people to vote would have an impact, particularly in areas where elections are on the horizon (for example, metro mayor and local elections in England). 16- and 17-years olds will be entitled to vote for the first time in the Welsh Senedd elections in 2021 but are still denied the vote for council elections in England or Northern Ireland, or for the UK Parliament or Northern Ireland Assembly.83 The UK government should reduce the age of voting to 16, starting with the local and Mayoral elections in 2021.

Austerity heightened the importance of grassroots organisations just at the time as councils legally had to concentrate resources on statutory functions. For example, the role of "friends groups" in looking after parks or volunteer-run food banks. Local sports clubs, which are so important for the mental and physical health particularly of young people, saw the financial support from local authorities decline and they already faced funding gaps before COVID-19.84 Fields in Trust highlight the risk to green space locally as funding pressures creates pressures for councils to allow sales to go ahead.85

The government has recognised the importance of grassroots organisations in its Civil Society Strategy in 2018, which it says "proposes significant reforms across the public and private sectors to build a fairer society [and] that people, communities and charitable organisations will be at the centre of decision-making."86 But the government has been strongly criticised for the lack of progress.87

COVID-19 has hit the finances of many voluntary organisations significantly, according to NCVO.88 But it has also again shone a light on the importance of them, for example through the work of mutual aid groups during lockdown. Volunteer local environmental groups, such as practical conservation groups or parks groups, will not be immune to the impact of the pandemic. They play an important role in the restoration of biodiversity, but also increasingly link up with health practitioners who carry our social prescribing for physical or mental challenges such as loneliness. The #NeverMoreNeeded campaign has highlighted the deficiencies of the government’s support to grassroots organisations to date.89

A large range of organisations invest in the grassroots but there is still a very significant shortfall of monies needed to ensure vibrant grassroots activities, including environmental. COVID-19 Recovery Plans must include funds for grassroots and community organisations, including environmental groups, to weather the current crisis but also to build back better and stronger. The Welsh government used World Environment Day to announce new resources for groups involved in local nature or woodland creation projects as an area that needs action in the COVID-19 context. This is a step in the right direction, but more is needed across the UK.

Mike Childs, Head of Policy

June 2020

Annex – list of all policy recommendations

Prioritise health and wellbeing

Make cycling and walking safe and easy, by spending £2 billion a year on them.

- As part of the COVID-19 Recovery Plan the UK government must commit to spending £2 billion a year on walking and cycling.

- COVID-19 Recovery Plans must go further and enable temporary changes to reallocate road space to pedestrians and cyclists to be made permanent.

Reduce air pollution to World Health Organisation standards by 2030 including by investing £8 billion additional money annually into clean, affordable public transport.

- The Environment Bill should include a 2030 target as the latest date for air quality to meet WHO standards, as should a Clean Air Act in Wales.

- The government and devolved nations must set a target to double the proportion of people that travel by walking, cycling and public transport by 2030.

- The UK COVID-19 Recovery Plan must set a pathway for rapid railway renationalisation and local authority bus franchising. In Wales, the Government is supportive of bus franchising but need to fast-track the action needed to make it happen.

- The UK government COVID-19 Recovery Plan must invest at least £1.3 billion a year more on buses, £5.52 billion on rail, and at least £1 billion a year on new trams, and this should be in addition to the extra funds provided to compensate for falling passenger numbers.

- ULEZs must be funded as part of COVID-19 Recovery Plans, and their introduction should not be delayed.

- The UK government scrappage scheme should go further by supporting a modal shift in preference to a new car purchase, including the purchase of a bike or e-bike and public transport tickets to support the growth of the most sustainable forms of transport

Ensure access to high quality, nature-rich, green spaces for all.

- Friends of the Earth is calling for UK tree cover to be doubled and for the minimum urban 20% tree cover target to be met, and COVID-19 Recovery Plans should work towards this.

- COVID-19 Recovery Plans and planning policy must require and enable local authorities to meet quantity and quality green space standards that enable healthy living and help restore nature.

- The UK COVID-19 Recovery Plan must increase funding for national nature restoration, including £0.8 billion a year for habitat creation (including afforestation to move towards a target of doubling tree cover) and £2.6 billion a year on environmental land management to ensure public money paid to farmers is used for public goods as recommended by the Greener UK coalition.

Enshrine a right to a Healthy Environment in law.

- The UK COVID-19 Recovery Plan should commit to introducing a new law to provide people with a Right to a Healthy Environment as one of the tools for eliminating health inequalities that result from a degraded and polluted environment.

Put green jobs and livelihoods at the heart of the recovery

Create 40,000 new jobs and eradicate fuel poverty by rolling out a massive programme of home insulation.

- The UK government and devolved nations should use COVID-19 Recovery Plans to bring all homes up to a decent energy efficient standard by 2030 (at least EPC C standard) and collectively install an average of 1 million heat pumps per year.

- In total, over the next two years COVID-19 Recovery Plans should invest at least £10.5 billion into energy efficiency and heating.

- The UK government must, as part of the COVID-19 Recovery Plan, set mandatory energy efficiency targets for homes in the private-rented sector to be energy efficient (EPC C level) by 2030 at the latest, with interim legally binding milestones.

- The UK government should follow the lead of the Scottish government and set energy efficiency standards that owner-occupied homes should meet.

Quadruple the rate of renewable energy construction to create tens of thousands of new jobs.

- The UK government must remove the de facto ban on onshore wind in England in its COVID-19 Recovery Plan and remove the cap that limits the amount of new renewable energy capacity supported through CfD (contract for difference) auctions.

- The UK government and nations must collectively aim for 14GW of new renewable energy capacity year on year.

Guarantee green jobs or training for those made unemployed because of COVID-19.

- The UK government should work with the nations to introduce a jobs guarantee scheme for those made unemployed due to COVID-19, with the central aim of skilling up people to work in the green economy.

- The UK COVID-19 Recovery plan must enable councils to accelerate low carbon skills development by joining up the National Skills Fund, the National Retraining Scheme and the Apprenticeship Levy at local level and align this with place-based employment and business support systems. The devolved nations' COVID-19 recovery plans similarly need to give high priority for accelerating and simplifying training programmes.

Help transition workers from polluting into clean industries with a £4.3 billion a year transition fund.

- The UK government’s COVID-19 Recovery Plan should say that after 2030 only pure electric new cars and vans can be sold.

- The UK government should fund the transition with £4.32 billion each year and work with devolved nations, councils, unions, and employers to develop locally relevant transition plans to fund skills development, retraining, and for local investment to develop new employment within the areas.

Fix the broken economy so that it works for all people and planet

Help fund the recovery by removing tax breaks from big polluters, taxing polluting activities and scrap spending on climate-wrecking infrastructure.

- The UK government should announce within its COVID-19 recovery package that it is scrapping its Roads Investment Strategy and HS2 to use the funds to deliver projects which will create jobs in the green economy, from housing retrofits to low carbon transport and nature restoration (including in towns and cities).

- The UK government is expected to announce some tax changes as part of its COVID-19 Recovery Plan. It should announce new carbon taxes such as those recommended by the Grantham Institute, including a Frequent Flyer Levy and road user charging in the form of an eco-levy.

Financial bailouts of failing companies must come with strict conditions to protect workers' jobs and ensure the company is cutting emissions in line with the Paris Agreement.

- Any COVID-19 Recovery Plans that include bailouts for fossil-fuel industries must have conditions attached so that the companies involved are swiftly reducing emissions from their operations and use of their products so that a rapid transition to net zero is achieved.

Measure the impact of the COVID-19 Recovery Plan by how it improves people’s lives not economic growth (GDP).

- The UK government, devolved nations, and local authorities should explicitly identify that the metrics to judge success of the COVID-19 Recovery Plans are how well they reduce poverty, decrease inequalities, meet carbon reduction and nature restoration goals, and contribute to the global delivery of the Sustainable Development Goals and not GDP.

Co-operate globally and act responsibly

Provide our fair share of climate finance to support the transition of the world’s poorer nations.

- It is essential that the UK’s COVID-19 Recovery Plan significantly increases UK international climate finance to our fair share, which is probably at least a tenfold increase on current levels.

End UK government investment in overseas coal, oil and gas projects

- The UK COVID-19 Recovery Plan to commit to stopping all funding of fossil fuel extraction overseas.

Only do trade deals that guarantee the highest standards of environmental and public health protection.

- The government must guarantee environmental standards, establish a strong UK environmental watchdog, and enshrine principles such as the precautionary approach in UK law. They must do this before the end of the transition period.

- In a number of pieces of legislation currently before Parliament, the government must say no to any trade deal that weakens environmental, safety or consumer standards. And it must take the time to develop a world-leading trade policy which puts our environmental ambition at its heart.

Empower communities to lead the recovery

Provide nations and councils with the significant new powers and resources they need to deliver an inclusive and green recovery in their area.

- The UK COVID-19 Recovery Plan must provide nations and councils with the significant new powers and resources they need to deliver an inclusive and green recovery in their area.

Require decision-makers at all levels to demonstrate that the voice of those most directly affected by environmental harm is heard in the development of COVID-19 Recovery Plans.

- COVID-19 Recovery Plans should be developed in line with the rights and visionary democratic principles of the Aarhus Convention, and the processes used should be documented and available for public scrutiny. The UK should also begin the process of fully implementing the Aarhus Convention in a new Aarhus Act.

- The UK government should reduce the age of voting to 16, starting with the local and Mayoral elections in 2021.

Help grassroots and community organisations through the COVID-19 crisis and invest to enable them to build back stronger.

- COVID-19 Recovery Plans must include funds for grassroots and community organisations, including environmental groups, to weather the current crisis but also to build back better and stronger.

- 1Lambertini et al, 2020, Coronavirus is a warning to us to mend our broken relationship with nature, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jun/17/coronavirus-warning-broken-relationship-nature

- 2Watts et al, 2019, Coronavirus is a warning to us to mend our broken relationship with nature, The Lancet, Volume 394, Issue 10211, P1836-1878, November 16, 2019, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)32596-6/fulltext

- 3Environmental Audit Committee, 2020, NHS and Public Health England failing to do enough to tackle harmful emissions, https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/62/environmental-audit-committee/news/146908/nhs-and-public-health-england-failing-to-do-enough-to-tackle-harmful-emissions/

- 4Friends of the Earth et al, 2019, Investment for a greener and fairer economy https://policy.friendsoftheearth.uk/download/government-spending-needed-climate-and-nature-emergency

- 5Dornier, 2020, Nearly 4 in 5 Leeds residents want cars to give way to bikes, buses and walking to tackle urban air pollution, Transport and Environment, https://www.transportenvironment.org/press/nearly-4-5-leeds-residents-want-cars-give-way-bikes-buses-and-walking-tackle-urban-air

- 6Sloman and Hopkinson, 2019, Segregated cycleways and e-bikes - the future of urban travel , Friends of the Earth, https://policy.friendsoftheearth.uk/insight/segregated-cycleways-and-e-bikes-future-urban-travel

- 7Air Quality News, 21st May 2020, E-bikes could slash transport emissions by 50%, https://airqualitynews.com/2020/05/21/e-bikes-could-slash-transport-emissions-by-50/

- 8Gov.uk, 30 January 2020, Ethnicity facts and figures, https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/culture-and-community/transport/car-or-van-ownership/latest#:~:text=Summary%20of%20Car%20or%20van%20ownership%20By%20ethnicity%20Summary&text=of%20all%20the%20ethnic%20groups,and%2017%25%20of%20White%20people

- 9Ritchie and Rosser, November 2019, Air Pollution, Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/air-pollution#:~:text=Air%20pollution%20is%20one%20of%20the%20world's%20leading%20risk%20factors,risk%20factors%20for%20disease%20burden.

- 10Travaglio et al, 2020, Links between air pollution and COVID-19 in England, MedRxIV, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.16.20067405v5

- 11Sloman and Hopkinson, 2019, A radical transport response to the climate emergency , Friends of the Earth, https://policy.friendsoftheearth.uk/insight/radical-transport-response-climate-emergency

- 12Pickard et al, June 18 2020, UK rail bailout hits £3.5bn and set to rise further , FT, https://www.ft.com/content/24e57a49-03e6-4106-9f7c-b630fdb76e28

- 13Friends of the Earth, 2019, ULEZ a ‘crucial’ step in the fight for clean air, https://friendsoftheearth.uk/clean-air/ulez-crucial-step-fight-clean-air

- 14Beiker and Mock, 2020, Green vehicle replacement programs as a response to the COVID-19 crisis: Lessons learned from past programs and guidelines for the future, ICCT, https://theicct.org/publications/vehicle-replacement-programs-covid-19-may2020

- 152 hectares of green space with a 5-minute walk is the current standard, recommended by Natural England. They are currently updating the standard.

- 16Office for National Statistics, 2020, One in eight British households has no garden, https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/articles/oneineightbritishhouseholdshasnogarden/2020-05-14

- 17Urban Forestry and Woodland Advisory Committee Network, undated, England’s Urban Forests Using tree canopy cover data to secure the benefits of the urban forest, https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/tree-canopy-cover-leaflet/

- 18Environmental Audit Committee, 2020, NHS and Public Health England failing to do enough to tackle harmful emissions, https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/62/environmental-audit-committee/news/146908/nhs-and-public-health-england-failing-to-do-enough-to-tackle-harmful-emissions/

- 19Spiers, 2019, Greener UK Manifesto Asks, Greener UK, https://greeneruk.org/sites/default/files/download/2019-10/Greener_UK_Manifesto_asks_Nov.pdf

- 20United Nations, 2018, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N18/231/04/PDF/N1823104.pdf?OpenElement

- 21Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015, https://futuregenerations.wales/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WFGAct-English.pdf

- 22Energy UK, 2020, Rebuilding the UK economy: Fairer, cleaner, more resilient, https://www.energy-uk.org.uk/media-and-campaigns/press-releases/463-2020/7564-energy-can-help-power-economic-recovery.html

- 23Ecuity Consulting, 2020, Local green jobs – accelerating a sustainable economic recovery, Local Government Association, https://www.local.gov.uk/local-green-jobs-accelerating-sustainable-economic-recovery

- 24EEIG, 2020, REBUILDING FOR RESILIENCE - ENERGY EFFICIENCY’S OFFER FOR A NET ZERO COMPATIBLE STIMULUS AND RECOVERY, https://www.theeeig.co.uk/news/starstarnew-reportstarstar-rebuilding-for-resilience-energy-efficiency-s-offer-for-a-net-zero-compatible-stimulus-and-recovery/

- 25Vivid Economics, 2020, A UK Investment Strategy, https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/uk-investment-strategy-building-back-resilient-and-sustainable-economy

- 26IPPR Environmental Justice commission, 2020, FASTER, FURTHER, FAIRER PUTTING PEOPLE AT THE HEART OF TACKLING THE CLIMATE AND NATURE EMERGENCY, https://www.ippr.org/files/2020-05/faster-further-fairer-ejc-interim-may20.pdf

- 27Rosenow and Thomas, 2020, Net zero is nowhere in sight for UK clean heat policy, Green Alliance, https://greenallianceblog.org.uk/2020/05/13/net-zero-is-nowhere-in-sight-for-uk-clean-heat-policy/

- 28EEIG, 2020, REBUILDING FOR RESILIENCE - ENERGY EFFICIENCY’S OFFER FOR A NET ZERO COMPATIBLE STIMULUS AND RECOVERY, https://www.theeeig.co.uk/news/starstarnew-reportstarstar-rebuilding-for-resilience-energy-efficiency-s-offer-for-a-net-zero-compatible-stimulus-and-recovery/

- 29Friends of the Earth et al, 2019, Government investment for a greener and fairer economy, https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Government-Investment-for-a-greener-and-fairer-economy-FINAL-30.08.19.pdf

- 30Gov,UK, 2020, Section 6 – UK Renewables 2019 and October to December 2019, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/875410/Renewables_Q4_2019.pdf

- 31Childs, 2019, Faster, deeper, and fairer carbon pollution cuts needed, Friends of the Earthhttps://policy.friendsoftheearth.uk/insight/faster-deeper-and-fairer-carbon-pollution-cuts-needed

- 32RSA, 2020, WHICH LOCAL AREAS ARE MOST AT RISK OF IMPACTS OF CORONAVIRUS ON EMPLOYMENT? https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/reports/local-areas-coronavirus-employment

- 33Social Market Foundation, 2020, Guarantee green jobs for coronavirus unemployed, https://www.smf.co.uk/smf-media-release-guarantee-green-jobs-for-coronavirus-unemployed/