01 Feb 2023

Summary of our policy asks

The UK’s reliance on gas for heating and electricity generation, combined with the poor energy efficiency of many homes, has led to severe economic impacts for the country and for householders, particularly those on low incomes, because of soaring gas prices. A rapid transition to an efficient and renewable energy system is needed.

Friends of the Earth believes significant policy change can address the energy crisis, transform our energy system and secure warm homes for all. The policies we’re seeking political support for are:

- No one left at risk by sky-high energy bills.

The government must ensure everyone can afford the energy they need to keep their homes warm. Despite some emergency support, millions of people are still facing impossible choices between staying warm and being able to put food on the table. Far more help is needed – through price guarantees, targeted extra payments and fair energy pricing. The government must make sure nobody has to choose between heating and eating.

- A national insulation drive.

We need a rapid programme of installing basic insulation measures, co-ordinated by councils and delivered street by street. By starting in energy crisis hotspots, where incomes are below average but energy use is high, the programme will ensure the fastest roll-out to the homes that most urgently need support to bring down their bills. In areas where people are living on low incomes, energy saving measures should be provided free of charge. This initial 2–3-year energy efficiency programme must be followed up with deeper measures to upgrade our homes to ensure they’re cheap to heat and fit for the future by 2030. To achieve both these basic and deeper measures, the government must invest around £8 billion a year over the next decade.

- An energy system powered by cheap and green renewables.

To remove the need for expensive and polluting gas in the long term, we must move to a homegrown renewable energy system. Providing the UK’s heating without having to rely on volatile global gas markets requires fitting millions of homes with modern electric-powered heat pumps. To heat and power our homes with clean, renewable energy, we also need a rapid expansion of onshore wind and solar power across the UK, as well as our vast offshore renewable resources.

Context

Millions of people are struggling to heat their homes and pay their energy bills because of the high price of gas, despite the significant support the government is currently providing. This is particularly true in the private-rented sector – where the typical energy performance of homes is low and the cost of renting is high – and for those on pre-payment meters1 who can’t spread heating costs throughout the year and who are typically on lower incomes.

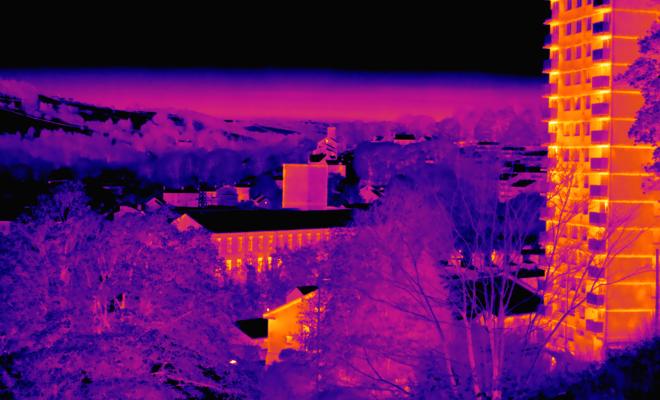

The poor condition of the UK’s housing stock makes the situation worse. 19 million UK homes aren’t energy efficient, meaning they’re below Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) C level. Currently it costs £450 more per year to heat a home rated EPC D than a home rated EPC C, and £1,350 more for a home rated EPC E. This price difference will increase once the energy price cap is increased to £3,000 in April 2023.

Millions of homes don’t even have basic insulation. Government data says there are 5.7 million homes that need loft insulation fitted, including topping up lofts that don’t have sufficiently deep insulation, and 3.8 million homes that need cavity wall insulation.

While high energy costs may make it cost-effective for households that can afford it to invest in energy efficiency measures, there are millions who aren’t able to afford this investment. According to research by insulation company Kingfisher, a third of people can’t afford the upfront costs of insulation. And higher energy costs won’t give owners of rented properties a reason to invest if the tenants pay the bills.

Poor levels of home energy efficiency are also a climate change issue. The devastating floods in Pakistan and the extreme heat in the UK in 2022 are a stark reminder that climate change is an existential threat to many countries and their people. Heating of buildings is responsible for more than a fifth of UK greenhouse gas emissions. These emissions must reduce sharply if the UK is to meet its carbon reduction target of 68% by 2030, a target reiterated by the prime minister at the COP27 international climate negotiations in Egypt in November 2022. The Climate Change Committee, the government’s official climate advisor, has stated that "reducing energy demand in UK buildings is now the biggest gap in current Government energy policy".

While the housing retrofit challenge – which includes changing heating systems from gas to modern electric heat pumps – may sound daunting, it also promises substantial economic benefits for both householders and government. It’ll bring job opportunities – research by IPPR North suggested a retrofit programme could create 77,000 jobs in the north of England alone – as well as other economic benefits, such as reduced demand on the NHS to deal with the health effects of people living in cold homes.

1. Financial support

The government has already offered substantial support to householders through:

- the Energy Price Guarantee (EPG), which currently caps energy bills for a typical home at £2,500 a year until April 2023

- a £400 contribution to all householders’ energy bills

- additional cost-of-living support measures worth as much as £1,200 for some households.

This support has been very welcome, although the government acknowledges it’s been poorly targeted.

The government announced in its 2022 Autumn Statement that the cap on energy bills will rise to £3,000 for the financial year 1 April 2023 to 31 March 2024. It also announced a £900 cost-of-living payment to those receiving means-tested benefits, an additional £300 for pensioners and an additional £150 for those receiving disability benefits. In addition, it’s committed to increasing benefits in line with inflation.

While welcome, these payments will still leave those receiving means-tested benefits worse off than before the energy crisis, with typical energy bills £1,900 higher. And those in poverty but not receiving benefit payments – around 4 in 10 of the bottom income quintile according to the Resolution Foundation – will clearly be in a much worse position. The Social Market Foundation has identified that, of 12 million households that'll be in fuel poverty from April 2023 (defined as households spending more than 10% of their income on energy after housing costs), only 6 million are receiving means-tested benefits or are disability claimants.

There’s no straight-forward answer to what’s needed, either in addition to the extra cost-of-living payments or instead of them. The government’s Autumn Statement said it’ll “work with consumer groups and industry to consider the best approach to consumer protection from April 2024, including options such as social tariffs”. A social tariff is a mechanism to charge a lower price of energy to low-income households. The Social Market Foundation has modelled a 30% discount on energy costs by unit of energy for those receiving means-tested benefits or those with incomes below £25,000. It found that this would benefit 8.3 million households by an average of £809 at a cost of £6.7 billion.

A supplement to a social tariff worth exploring is a Rising Block Tariff. This is where a first tranche of energy is provided free or at a low cost, with escalating prices for subsequent tranches of energy. It reduces the cost for low energy users and increases the cost for high users. The theory is that the policy is particularly beneficial for low-income householders, who on average use less energy, and that it incentivises energy reduction by high energy users, who are wealthier on average. However, early Friends of the Earth modelling suggests that if the policy were introduced on its own (ie without a social tariff), there would be an unacceptably high number of low-income, high-energy-use households that would face much higher bills – we estimate more than 1.5 million households with less than average incomes would be more than £1,500 worse off.

The Social Market Foundation reports that the support mechanism most favoured across Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat voters to date is a social tariff. It says the biggest challenge with all options is identifying all those in need of support.

Friends of the Earth will engage in the government’s consumer protection review, including to ensure any mechanisms chosen also support and incentivise decarbonisation. In the meantime, we’ll work with poverty organisations to push for greater targeted support for those who’ll still be in fuel poverty in 2023/24 despite the government’s planned additional cost-of-living payments.

2. Insulation and changing home heating systems

Financial support for householders is a necessary plaster for the bigger problems of the UK’s poorly insulated homes – said to be among the worst in Europe – and the UK’s reliance on fossil fuel gas.

Bringing the UK’s housing stock up to acceptable energy efficiency standards (EPC C) requires a 10–15-year programme. Before the energy crisis, the government set a target to ensure all homes reach EPC C by 2035 and to fit 600,000 heat pumps a year by 2028. We must move much more swiftly.

A rapid programme of basic insulation measures

In November 2022 the Climate Change Committee made the following recommendation to the government: "The next two years should be a period for a concerted push to improve rates of loft and cavity wall insulation, draught-proofing and installing modern tools to manage energy use (such as smart thermostats, thermostatic radiator controls and smart meters).”

This echoes Friends of the Earth’s repeated calls throughout 2022 for a rapid, street-by-street programme of basic insulation measures, first targeting the 8,927 neighbourhoods where incomes are below average but energy consumption is high (which we’re calling energy crisis hotspots). These communities have a greater proportion of people of colour living within them and a higher proportion of children.

Friends of the Earth is calling for this programme to be co-ordinated by councils – area by area, street by street – because this’ll bring significant efficiencies (ie installers save considerable time by not moving across towns and cities from one job to the next) and because historically such an approach has been shown to increase household participation. This co-ordination role by councils doesn’t mean they should deliver the insulation, not least because they don’t have the capacity and expertise to do so.

We’ve also called for this basic programme to be delivered free of charge to all households in low-income neighbourhoods, because of unaffordability and to avoid the bureaucratic and time-consuming burden of means-testing. The programme should include rented properties in these neighbourhoods because, while the property owner may benefit in terms of house value, bill-paying renters will experience the greater benefit.

The New Economics Foundation (NEF) carried out detailed modelling for Friends of the Earth on a street-by-street programme of basic measures – loft and cavity wall insulation, thermostatic radiator valves, draught-proofing, smart energy controls, and a £100 energy audit to provide bespoke advice. This modelling suggested an average cost of £764 per household in the neighbourhood studied. More recently, NEF has increased this estimate to £1,000 as an average across all neighbourhoods2. These costs don’t assume efficiencies from a street-by-street approach, which could be considerable.

The cost of this free, basic programme would therefore be £6.9 billion, or £5.2 billion with a 25% efficiency factor, for the 6.3 million homes in the 8,927 energy crisis hotspots Friends of the Earth has identified in England and Wales.

NEF estimates that the cost of providing this free basic insulation to all neighbourhoods across England would be £27.2 billion and that the annual saving created would be £9.6 billion based on the October 2022 energy price cap. Assuming a 25% efficiency factor, the cost would be £20.2 billion, or £15 billion if the 25% of wealthier neighbourhoods were excluded from this free programme. Friends of the Earth is calling for a £15 billion programme, spread over 3 years.

This approach of rapidly rolling out basic insulation won’t deliver the deeper retrofits needed to eliminate fuel poverty and ensure all homes are EPC C, but it will make a good contribution to both and will set the foundation for the additional work needed.

Deeper insulation and heat pumps

In addition to these basic measures, we need a programme of deeper retrofits, such as double glazing and solid wall insulation, to bring all homes up to EPC C standard. The Climate Change Committee has given indicative costs per household for the measures required, for example £6,900 for double glazing, £7,950 for internal solid wall insulation and £2,800 for underfloor insulation. Although these measures may have a long payback period, they’ll increase the comfort of homes, reduce health costs for the NHS, improve property values and cut emissions further.

The Social Market Foundation has estimated that the cost of bringing all homes up to EPC C standard in England would be £119 billion, and that this would save £10.2 billion in energy costs each year for householders, based on the typical energy price cap of £3,000 that’ll start in April 2023.

The cost of replacing a gas-fired boiler with a heat pump is often quoted as £11,000, but Octopus Energy and Halifax are offering heat pumps at £7,000 (so at a cost of £2,000 to the householder when using the government’s £5,000 Boiler Upgrade Scheme) to Halifax mortgage owners. While a heat pump won’t significantly reduce energy bills, it’ll reduce carbon emissions by around two-thirds. The advent of high-temperature heat pumps also makes heat pumps suitable for nearly all properties, with or without additional insulation, including solid-wall properties.

The Climate Change Committee has identified a range of policy levers that could be used to deliver deeper retrofit measures. These include:

- For “able-to-pay” owner-occupiers (those who can afford to install insulation or heat pumps) – zero- or low-interest loans, reduced stamp duty for energy-efficient homes, or stamp-duty rebates for purchasers if they improve the energy performance of their house within 2 years.

- For “unable-to-pay” owner-occupiers – obligations on energy companies (as currently exist) or boiler retailers (as proposed), and grants, for example through the Local Authority Delivery scheme.

- For the private-rented sector – increased Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) coupled with tax rebates.

Friends of the Earth supports financial incentives for the able-to-pay, but regulations are also likely to have a role. For the unable-to-pay, there needs to be grants to ensure these homes also benefit from insulation and the installation of heat pumps. Obligations on energy companies and boiler manufactures are also likely to be important.

For the rented sector, we’re particularly concerned that any measures introduced don’t result in higher rents or large numbers of properties being removed from the market. So, while we’re calling for MEES for private-rented properties to be strengthened so that all private-rented properties are EPC C by the end of 2028 at the latest – with a focus on ensuring the properties with the worst insulation standards are upgraded first – we also believe the cost for landlords of upgrading the homes should be tax deductible, as is currently the case for repairs3. There’s no good reason for landlords to put up rental costs because of tax-deductible improvements.

The private-rented sector also needs proper regulation, with councils required and funded to inspect homes and mandate any work needed to bring them up to standard. A compulsory register of landlords is needed to enable councils to carry out their regulatory duties. No-fault evictions should be outlawed – including removing the chilling effect on tenants who report sub-standard housing – and other changes to improve rental standards should be introduced, such as a decent homes standard and rental controls (like those used in Scotland).

The scale of government spending will depend on the package of measures. In 2019 green groups and development groups came together to identify the government spending needed to respond to the climate crisis, which included an investment of approximately £5.4 billion per year on energy efficiency for buildings and the installation of heat pumps. We were clear that this figure was a first step towards greater levels of spending required to transform heating in future years. With this in mind, and recognising the impact of the energy crisis, Friends of the Earth is now calling for an average annual investment of £8 billion a year over the next decade. This is well in excess of the £2 billion for 2025-2028 pledged in the government’s Autumn Statement and is also higher than the £6 billion a year the Labour Party is promising to spend if elected. This £8 billion per year includes the £15 billion basic insulation programme spread over 3 years.

Any policy package will also need to address the shortage of a skilled workforce. While basic insulation measures are straight forward, deeper retrofit measures require skilled workers, which in turn requires longer-term policy certainty to enable employers to make investment decisions on training.

3. Renewable energy and an upgraded network

Our energy system is very reliant on gas, which is why the UK has been particularly exposed to high gas prices. Gas is the main source of heating (80% of properties) and is used to generate more than a third of electricity. The price of electricity is also tied to the price of gas, which means that electricity generated from renewables is charged at the same price as electricity generated from gas, even if it’s much cheaper to generate. At the peak of gas prices, electricity was 9 times more expensive than the cost of generating renewable electricity. This reliance on gas has harmed the UK economy, and its use is a major contributor to the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The UK is blessed with exceptionally large renewable energy resources, both onshore and offshore. Transforming our energy system so that it’s powered by renewable energy – and backed up with long-term energy storage – is increasingly looking like the best economic choice for the country, as well as the best approach from environmental and energy security perspectives.

This’ll require the government’s Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme – which offers new renewable energy projects a guaranteed price for the electricity they produce – to facilitate the rapid growth of renewable power of all types. It’ll also require the government to remove unfair planning constraints on onshore wind in England.

In addition, the regulated electricity network operators will need to invest in upgrading transmission lines so that the network can cope when electric vehicles and heat pumps become the norm, as there’s been under-investment in the electricity network for a long time. Alternatively, there’s a compelling argument to bring disparate privatised network operators into public ownership, to operate as a single business (much like the argument for public ownership of the railways), and for public investment. Friends of the Earth is agnostic on the ownership model so long as the investment is made.

To ensure that householders and businesses benefit from low-cost renewables, it’s also necessary to change the energy markets so that the cost of electricity isn’t set by the cost of electricity produced from gas, meaning renewable energy could be much cheaper. The government has recently had a public consultation on such a reform.

The switch to heating powered by renewable power – primarily heat pumps – will take time. The timescale of the transformation may be as much as 15 years, but it needs to start now. The switch to a renewable electricity system can happen much faster. The government has set a goal for a low-carbon electricity system by 2035, although an earlier target is needed.

The UK can move beyond using gas and become a country powered by clean, homegrown renewable energy. And we don’t need further gas exploration in the meantime, because the transition can be fast if it’s prioritised by decision makers.

- 1Many people are being forced onto pre-payment meters, including through magistrates approving batches of requests from energy companies rather than looking at cases individually. The End Fuel Poverty Coalition, which Friends of the Earth supports, is calling for a ban on forced transfers.

- 2The neighbourhood NEF studied for the first estimate was a low-income area with smaller homes and more flats, hence the lower-than-average costs.

- 3There’ll likely need to be a cap on the level a landlord is required to spend. This needs to take into account the need for solid wall insulation in many older properties (estimated to cost £7,950 to £9,350: https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/letter-reducing-energy-demand-in-buildings-in-response-to-the-energy-price-crisis/), the need to replace gas-fired boilers by 2035, and also any potential impacts on the quantity of homes available to rent. The cap may also need to reflect regional differences in the capital value of properties. Further research is needed to identify the level of the cap. The aim should be that only a very small proportion of homes (eg 5%) remain lower than EPC C after 2028.