Camilla Zerr01 Dec 2021

There is little question that globally plastic pollution is a pervasive and growing problem. It’s been found in the highest mountains and deepest oceans, it’s choking our wildlife, it’s in the food we eat and the air we breathe. Up to 12 million tonnes of plastic end up in the sea each year, causing a terrible impact on ocean ecology and beaches and a real headache for waste management and disposal. Too often the onus is put on individuals to reduce the impact of our throw-away society. But without strong government action to create a level playing field for businesses sadly our individual efforts alone will never be enough to solve the problem.

Despite the need for bold action, it seems that the current UK government is entangled in a dangerously slow-moving and piecemeal approach to addressing the plastics crisis, celebrating bans on a few plastic items every year or so and championing so-called world-leading waste and resources strategies in which the focus is still on recycling rather than on reduction, re-use and the benefits of a circular economy. Former prime minister Boris Johnson even said that “recycling doesn’t work” and that we must cut down on the use of plastics.

No time for a piecemeal approach

It’s hard to justify this piecemeal approach at any time, but now, with the weight equivalent of 60,000 blue whales entering the ocean every year globally, and this amount set to triple by 2040, there is no more time for a product-by-product approach. It's not acceptable that three in four Brits reported feelings of “anxiety, frustration or hopelessness” at the amount of plastic packaging that comes with their shopping in our joint survey conducted last May 2021.

Friends of the Earth has been a champion of re-use and recycling since our founding in 1972. Indeed our first action was to dump thousands of bottles outside Schweppes headquarters to demand it restore returnable bottles. And we were instrumental in getting the doorstep recycling Act into parliament.

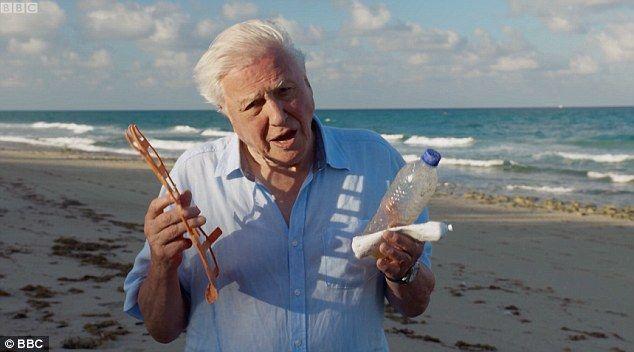

I joined the organisation as Plastics campaigner in 2020 and have been shocked at how little official progress has been made since then. And this is despite the game-changing Blue Planet 2 plastics episode, which was aired 4 years ago, although the alarm bells sadly didn’t translate into meaningful overarching plastics reduction policies from government.

Here are some of my reflections on the government’s current approach.

Plastics reduction and the Environment Act

On 10 November 2021, 1056 days after its first draft was published, the Environment Act– which meant to set world-leading environmental protections – became law. Its meandering journey of delay after delay was justified by the government as necessary to ensure it delivered the strongest environmental outcomes possible.

However, this new legislation is riddled with omissions and loopholes. It is a pale shadow of what’s required to protect and enhance our environment. And one of the gaping holes is the lack of any guarantee that this bill will meaningfully reduce plastic pollution.

This is despite the government having had multiple opportunities this year to introduce a plastics reduction target to the new law as it was being debated in Parliament, like the similar targets which were set to clean up air pollution and halt species decline.

Missed opportunities

In the House of Commons in January 2021, a Conservative-led plastics reduction amendment was tabled and supported by 16 cross-party MPs. This new clause would have required the Secretary of State to set targets to reduce plastic pollution and reduce the volume of non-essential single-use plastic products sold. The amendment’s intention was welcomed by government.

In the House of Lords in September 2021, a similar plastics reduction amendment was taken to a vote, which was lost by only 26 votes, with 81 peers voting in favour. This was despite 49 organisations such as Surfers Against Sewage, Keep Britain Tidy, the Women’s Institute and City to Sea showing support for these amendments in a letter to the prime minister alongside businesses, faith, academics, students and environmental charities.

The result of the vote also contradicts Minister Zac Goldsmith’s speech on the 13 September 2021 in which he said “There is a particular and acute need to reduce our consumption of single-use plastic and the particular and enormous environmental harm that it causes, [including via] a powerful and targeted tool [in the bill].” But as the Environment Bill became an act in law, an overarching target to specifically address the problem of reducing all types of plastic pollution as separate from other materials is still missing from UK legislation.

So what have I learnt about the huge gaps in the UK government’s approach to addressing plastic pollution?

1. Current UK legislation and policy are nowhere near enough to tackle the plastic pollution crisis.

Government’s response to every letter, parliamentary question, parliamentary debate or question at events on reducing plastic pollution has been the same for years: we are already world-leading, and here’s a list of all the amazing plastics measures we’ve taken. And then comes the overwhelming list: a world first ban on microbeads, a ban on single-use plastic straws, drink stirrers and cotton buds, a single-use carrier bag charge, an ambition to eliminate all avoidable plastic waste by the end of 2042, powers to create Extended Producer Responsibility Schemes and Deposit Return Schemes, the introduction of more consistency in recycling, an upcoming tax on plastic packaging etc. And let’s not forget the £500 million Blue Planet Fund and the UK’s leadership in setting up the Commonwealth Clean Ocean Alliance alongside Vanuatu.

These measures while good in themselves, are likely to only address 4 of the top 10 types of plastic pollution - and do so only partially. Whether this list is deliberately trying to blind us to this fact, or whether some government representatives truly are satisfied with current plastics legislation and see no need for improvement, remains somewhat a mystery, perhaps lost in translation between the government’s rhetoric on waste reduction but lack of any impactful action or policies to back this up. Or could it be that some government officials with power have vested interests in keeping the plastic tap flowing?

2. The UK government’s approach is too slow and risks diverting from the urgently needed move towards reduction, reuse and a circular economy.

UK legislation and policies, including the Environment Act, currently adopt a fragmented approach to reducing plastic pollution. They focus on end-of-life solutions - such as Deposit Return Schemes & Extended Producer Responsibility – rather than the full plastics lifecycle.

They introduce powers to charge for single-use plastics, which without a holistic overarching target to reduce all types of plastic pollution, further entrenches a slow-moving “one plastic product at a time” approach.

3. Addressing plastics reduction via a resource efficiency lens overlooks major types of plastic pollution in the UK.

The government has repeatedly extended assurances that its 2018 Waste & Resources Strategy adequately addresses plastic pollution – whilst in reality, most of the policies focus on recycling with very little attention given to reducing the consumption of plastics and other materials in the first place, and prioritising reuse. The same trend can be observed in the new Environment Act, in which Ministers have reassured MPs and the public that the resource efficiency and waste reduction priority area for setting a target will deliver the plastic pollution reductions we are calling for.

However, this is not true, as efforts to boost resource efficiency will make only a partial contribution at best to reducing plastic pollution. This is because resource efficiency is measured primarily by the energy or weight of materials used, and therefore overlooks major types of plastic pollution in the UK, including products that are efficiently designed but still cause plastic pollution, such as lightweight polystyrene packaging, plastic film wraps and plastic bottles and microplastics, generated from the breakdown of products such as polystyrene packaging, polyester fleeces and vehicle tyres. Current UK legislation is estimated to address less than 1% of pollution from microplastics, although microplastics are estimated to contribute to over half of the UK’s plastic pollution.

4. The government’s role in global plastics-related alliances and funding should not exclude the UK from setting domestic targets to reduce plastic pollution.

Another common line used by the government to justify not doing more to reduce plastic pollution is that it's leading global initiatives to clean up our oceans and fund marine litter programs.

However, this does not exclude the UK from setting domestic targets to reduce plastic pollution. If we compare this to government action on climate, the UK was responsible for passing the Climate Act in 2008, a world-renowned piece of legislation that set domestic targets for reducing carbon pollution year on year at the same time as playing its part in the UNFCCC global carbon reduction process.

Both carbon and plastic are transboundary global issues, but the government has shown that it can be a leader in setting carbon budgets domestically. The same approach needs to be taken for plastic pollution.

It’s not too late

What is the solution to government's frustratingly inadequate and piecemeal approach to plastics so far?

The good news is that clearly joining up government’s current plastics-related measures under a simple, overarching target to reduce all types of plastic pollution year on year is still possible. The Environment Act’s target-setting process is well on its way, with a public consultation on draft targets expected in February 2022, and a due date of 31st October 2022 for these targets to be set in law.

Friday 10th December is the 4-year anniversary of the influential Blue Planet episode on plastics, so it rightly feels like time is running out to face up to the plastics challenge, especially considering recent survey results showing that the UK public are more concerned about plastic pollution than ever.

The government has a unique chance to set the distinct plastics reduction target we urgently need by October 2022 at the latest, via the Environment Act target-setting process. And the environmental sector, business, faith groups, academics, students and young people are geared up to make the case for such a target impossible to ignore.