Naomi Luhde-Thompson, Senior Planner14 Jan 2021

We live in places shaped by land-use planning. Step out of the front door and we step into a place formed by planning rules. As citizens we have immense power to influence the thousands and thousands of development decisions made every year in England. From our health to our work, our home to our community, there are buildings and spaces that have been and will continue to be shaped by planning decisions.

Take the town centre. The local council controls what space is used for – if a creche wants to change into a residential home on the high street, then planning permission needs to be obtained.

Or take the local park. The council controls its protection as well as its upkeep. A developer might think it’s up for grabs, but the local council can protect it by putting it in the local plan and writing a policy that says it won’t be developed.

What about tackling climate change?

Building any kind of renewable energy requires permission, except for solar panels on roofs of a certain size and type. So, if we want to build a 100% renewable energy system, then it needs to be approved by either the local council or the relevant minister for the biggest projects. To adapt to sea-level rise and flooding, local councils need to make sure that floodplains are protected, and that development is refused if it’s at risk. Councils can use their planning powers to insist on new build that minimises the energy needed for heating and new development that’s really helping to deal with increased rainfall and incorporates space for wildlife to thrive.

Democracy in action

Development needs permission and consultation is built into the application process. So we can say what we think when developments are proposed and then the decision is made by the local authority. If it’s a significant decision, it’s made by our elected councillors.

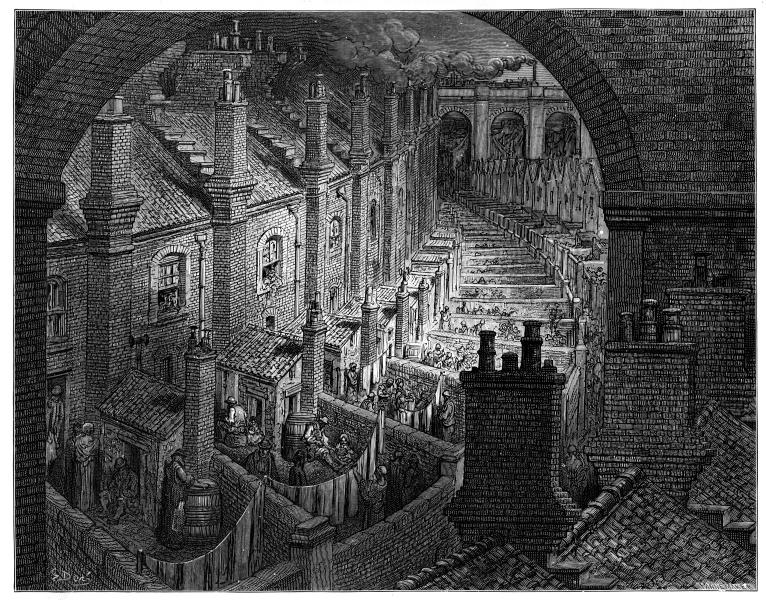

It’s all about control – who controls what happens and where. Planning grew out of the terrible impacts of uncontrolled development – the diseases and pollution that caused enormous suffering in rapidly urbanising Victorian cities.

With just a few people in a community, the environment can absorb the impacts – the smoke from the fires, the waste from the toilets, the discarded rubbish. But when you get thousands of people crammed together, the environment can’t absorb these impacts any more. Society has had to organise how to manage these impacts together.

A new social contract

After the second world war there was a new social contract. It was no longer acceptable that the damaging impacts of development, driven by private interests, were imposed on society. Instead, the “public interest” became the driving force behind development. Decisions from then on were meant to be determined by what was best for everyone rather than a select few.

"The objects of town and country planning are becoming increasingly understood and accepted. Primarily, they are to secure a proper balance between the competing demands for land, so that all the land of the country is used in the best interests of the whole people. This is especially necessary in these small, densely populated islands.” Lewis Silkin, 1947

But, as exemplified by this government’s proposed planning reforms, there’s a move away from trying to do things that are right for the community towards a much more arbitrary imperative – “we need to get houses built” – as if that’s all the planning system is fit for.

Over a million planning permissions remain unbuilt in England, so why do we need planning reform? There doesn’t seem to be a problem with getting consent. In fact, many feel that too much bad development gets consent and too easily. The planning system feels broken. Matters that are important to us like clean air, access to green space and climate breakdown, are trumped time and again by the supposed overriding need for economic growth.

Who’s in charge now?

The really big issue, however, is power and control. Many of us might feel that private developers are in charge already. And with these proposed reforms, the government in England is about to privatise the planning system on a scale that effectively reverses the post-war understanding that planning is for everyone and not just the few.

”Radical reform unlike anything we have seen since the Second World War...And, above all, that gives the people of this country the homes we need in the places we want to live at prices we can afford, so that all of us are free to live where we can connect our talents with opportunity.” Former prime minister Boris Johnson, 2020

Under these reforms, so much development will be essentially being privatised. Many decisions that were previously made by local councils will now become automatic approvals if the development meets seven criteria. These can be summarised as whether or not it is located in an area of high flood risk; site access; contamination of the existing property; noise; adequate light (but not windows specifically/view); fire safety; conflict with other existing uses of waste management or heavy industry. So not a lot of reasons to refuse… and the list doesn’t include climate change or good design.

The danger of permitted development

This kind of approval is called "permitted development" – it’s a powerful example of how control is being taken from the local level and handed over to property owners in England.

We’re all losing our voices in what happens where. It’s been happening gradually over the last ten years as local participation has been undermined. But now it’s culminated in a devastating and wholesale removal of democratic decision-making from planning.

Currently we have power – a right to object – and we have democratic accountability. But with the government’s new proposals, our rights will disappear on most housing developments or change of use from business to housing. The government is spinning this as greater public participation and civic engagement. Don’t be fooled. It isn’t. Hitherto, planning was about the public interest, the collective. But more and more it seems to favour a few profit margins, as the once powerful local collective voice is stripped out and environmental considerations set aside.

We have to protect our planning system. Like it or not, it gives us the power to make our local community a better more sustainable place – a system that we can’t do without when we have so little time left to address the climate and ecological crises.

We've signed a joint letter, together with 18 other organisations, urging government to think again about its proposals.