10 Feb 2025

A printable version of this discussion paper is available for download:

Part 1: Context

Introduction

The development of artificial intelligence (AI) has been exponential, and its use is permeating all corners of society – from government to the health sector to manufacturing and the creative industries. Along with its undoubted benefits in some areas, there are also risks, not least in the enormous environmental impact of its operation and the potential for some elements of society to be left behind.

This paper is primarily aimed at an audience of environmental justice organisations and digital rights campaigners looking to utilise AI in their work and to advocate for sustainability, equality and human rights in the digital sphere. We’ve attempted to unpack the challenges and opportunities that face both larger organisations and those with more limited means to suggest a number of principles that can inform and guide responsible AI practices.

We’ve arrived at these principles through research and interviews with environmental justice and digital rights campaigners. This included a lively roundtable event, where invited panellists and observers had the opportunity to comment on a draft of these principles. Quotations included in this paper without further references are taken from a transcript of the roundtable discussion.

We recognise that despite the environmental impacts, there are potential benefits in using these tools to address the climate crisis. It’s essential that, as campaigners and activists, we think now about how we use AI in the future, both to advocate for better public policies and to avoid discriminating and exploitative practices in our own choices and approaches.

Although we've attempted to use jargon-free language, there are some technical terms relating to AI which are explained in the glossary of terms towards the end of this paper.

Just enough

Much of the existing advice to organisations and communities about AI suggests developing shared principles and guidelines for responsible AI use. Together with our colleagues, peers and contemporaries, we advocate for policies that promote “just enough” approaches, which foreground ethical and sustainable AI practices.1 The concept of "just enough" internet was first developed by Rachel Coldicutt in 2019, where she made the case for avoiding technology for its own sake, and 'automating with care and sometimes not at all.'

[My approach is to] adopt a practice of just enough. Just enough technology, just enough energy consumption, just enough AI to do what we want to do, what we need to do, and no more. I'm just not sure that current forms of AI are suitable for that, so I would encourage resistance, care and critical thinking around any approach to AI.

(Marcus Berdaut, Creative Producer, The Upsetters)2

The impacts of the Big Tech approach

We use the term “Big Tech” in this paper to refer to influential, multi-billion dollar technology companies whose business models and practices have changed the fabric of society. There are upsides to these changes but also many downsides. From anorexia-promoting algorithms to data-driven disinformation, Big Tech has often explicitly ignored expert advice on the psychological and social impacts of these technologies. When it comes to AI, they can again be accused of ignoring the major impacts of their drive towards market dominance.

In stark contrast to Big Tech's exhortation to “move fast and break things,” civil society organisations and activists wish to prioritise the public and planetary benefits of AI over technological advances. They encourage moving more slowly, promoting transparency and accountability in AI systems, and ensuring that they’re designed and used in a way that respects human rights and environmental sustainability.

To that end, we’ve developed 7 principles activists can use to guide personal and organisational choices around AI. These principles can help campaigners work together to push for policies and regulations that protect the most vulnerable in society — those already at risk from systemic inequalities such as those doing precarious work — while also benefiting from the ways in which AI can help us address key issues. These principles are designed to help activist organisations find a balance. We want to ensure these technologies support the fight for a fair, fossil-free future, not undermine it.

The problem of polarising debate

The stories we tell one another influence our beliefs and behaviours. Stories that evoke strong emotions are more likely to be shared, and this in turn helps shape our understanding of the world around us. The rapid advance of generative AI has led to polarising views of AI in general, creating a binary framing that limits nuanced understanding and hinders informed decision making. According to these narratives, AI is either leading us to a dystopian future where current inequalities are exacerbated to the point of societal collapse, or it’s seen as a utopian solution that will fix our problems if we just keep going.

The utopian view

Companies like to say that AI is going to change the world. They say creating AI might do a bit of environmental damage now, but AI is also going to come up with the tools to solve that environmental damage, and it will all be worth it in the end. This is a moment for us to push back on that and question whether AI is ever going to have the capabilities in any form to be able to create this utopia. Whether we're willing to take that environmental risk, the damage that it's doing now in exchange for a utopia later. I personally don't think that we should.

(Samantha Ndiwalana, Ranking Digital Rights Research Lead, World Benchmarking Alliance)

The techno-solutionism inherent in the utopian vision insists that technology alone will solve the complex social and environmental problems faced by our societies. This obscures reality on the ground and the need for systemic change. It ignores the agency and power of our social and political solutions. It obscures the hidden costs of AI technology, both environmental and social, and the reality of the power dynamics at play in our societies. Market forces and Big Tech companies often control this narrative, attempting to wriggle out of their responsibility to create technology that benefits all of us, rather than a rich few.

It is also assumed that ‘AI’ is a neutral ‘good’ that can be ‘enjoyed’ equally by all, but generative AI models are data architectures that reflect the predominantly white, male, anglophone, instrumentalist world view of the data they were trained on. They do not equally represent all knowledge cultures and they cannot be used to equally enrich all people in their activities of knowledge production.

(Helen Beetham, Lecturer in Digital Education, University of Manchester)

Above all, AI is increasingly positioned as the key engine of (infinite) economic growth through productivity gains, with growth prioritised at all costs. In this framework, social and environmental impacts are positioned as an unfortunate externality, if they’re mentioned at all. As the research team at Careful Industries noted in a separate report for Friends of the Earth, “in a context where AI is being positioned as the golden ticket to efficiency and, therefore, economic growth, there is risk that this expansion will conflict with other policy priorities and environmental mandates.”3

The UK government’s AI Opportunities Action Plan, published in January 2025, is a particularly stark example. The plan contains no mention of the environment or climate and speaks only of “mitigating the sustainability and security risks of AI infrastructure, while positioning the UK to take advantage of opportunities to provide solutions.”

A contrasting narrative

On the other hand, the dystopian view of AI ignores the immense power that sophisticated technologies have to change the way our world works. It also dismisses our own agency and engagement. After all, it was only 35 years ago that the World Wide Web was invented, a project that was built as an open contribution to society as a whole. Despite global issues and challenges, we would argue that the web has changed the world for the better: social movements benefit from global amplification, activists focused on local issues can receive support and engagement from anywhere, and we can build collective power as we find each other through the web.

The dystopian story insists that integrating AI into our societies will accelerate planetary destruction and lead to further societal divides, as Big Tech abuses communities and the planet in its never-ending quest for more money and power. But technologies can be designed for both good and bad purposes and have both positive and negative outcomes. There are both enlightened, compassionate users and builders as well as cynical and uncaring ones. Our individual information landscapes, the strength of our local connections and communities, and even our upbringing influence how we see ourselves and the world and provoke feelings of hope or despair.

There are niche and optimistic visions we could use to try and inspire a different narrative. For example, “Solarpunk,” which started as a speculative fictional subgenre in 2008, envisions a world in which society and technology coexist sustainably in a post-capitalist civilisation. Marrying renewable energy, hope and the power of collectivism, Solarpunk projects encapsulate a sort of counter-culture activism that helps us see that there are many ways we can look at the relationship between ourselves and technology.

As campaigners unpack the nuances in the ethical and sustainable use of AI, they must lean on the expertise of leaders and organisations in both technology and sustainability. Blanket narratives about the use of AI aren’t helpful in the current socio-political climate, as they create a binary “them against us” approach which can turn off everyday users of technology.

Definitions of AI

It’s also important to understand that there are different kinds of AI and to form nuanced opinions and policies based on context. For the purposes of this paper, highlighting the differences between 3 predominant types of AI may help:

- Predictive AI refers to artificial intelligence systems that use statistical analysis and machine learning to analyse data, identify patterns and anticipate future events. It’s primarily used for decision making and planning based on data-driven insights. It has powerful applications in areas such as climate modelling, disaster risk reduction and optimising energy use. Predictive AI can also be used to help analyse data on public opinion, demographics and online behaviour to make campaigns more effective.

- Generative AI is a type of artificial intelligence that can create “original” content, such as text, images, audio, video or code, in response to user prompts or requests. It’s not only based on vast amounts of training data but also requires enormous amounts of computational power. In addition, each request made to such a system requires even more energy to generate an answer to the request. It’s often much more resource intensive than predictive AI. Generative AI is also associated with “hallucinations” (outputs that are plausible but not grounded in real data) and deepfakes (hyper-convincing false audio or video that can be used to show someone saying or doing something they never did or said).

- Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is a type of multi-purpose, often dystopian super intelligence that might surpass human capabilities in a range of domains. This kind of AI is often what’s being assumed in stories about an AI “takeover” or an existential risk from robots. This type of AI isn’t in scope for this paper. In line with the AI Now Institute, we argue that a focus on AGI is a distraction from the ways in which AI is already generating existential hazards in the present and near future for many of the most vulnerable populations.

In this paper, we focus on the use of generative AI within environmental justice and digital rights activist communities. Through our research and interviews, we’ve learned that there are people in these communities who believe that there can be no “ethical” use of generative AI due to who holds the power in AI development.

We respect and understand this perspective, acknowledging that resistance and refusal are important pillars in this activism, and wish primarily to augment that perspective with one that can direct our collective agency and power towards positive change. In doing so, we aim to create a new story for AI, somewhere in between dystopia and utopia. This story focuses on the structural issues associated with the ways in which AI concentrates power in the hands of a very small number of Big Tech firms, while still empowering activists and campaigners to live their values and utilise AI for good, particularly as new use cases emerge that may shift perspectives among both enthusiasts and critics.

Systemic complexities

Nothing is simple. We can’t treat AI as a standalone technology. We need to embrace complexity and the interconnectedness between technology, society and the environment. Civil society needs to work together to critically evaluate AI, resist techno-solutionism and challenge power dynamics to shape this conversation into one that benefits humanity. The relationship between AI and environmental justice is not only a consideration of the potential environmental impacts of using AI systems, but also of the interconnected impacts of the energy, minerals, labour, and infrastructure that AI systems require to function, as well as the potential futures AI enables.4

What happens with government changes? The Brazilian government used technology and geospatial data to protect indigenous lands and resources under the 1988 constitution and Lula's leadership. However, when Bolsonaro took power, this same data was used to systematically target and exploit the Amazon and its indigenous communities. In 2021, a case was brought to the Hague documenting unprecedented destruction under Bolsonaro's government. This case demonstrates how data collected for protection can be weaponized for destruction when custodians and their intentions change, serving as a warning about the dual-use nature of surveillance and mapping technologies.

(Melanie Rideout, AI Governance Fellow, Global Governance Institute)

The climate crisis disproportionately affects low-income communities, women and marginalised communities, such as people of colour and disabled people, that are already affected by systemic inequalities. We also know that “black-box” algorithms, a lack of regulation of corporate conglomerates and obscured climate impact reporting is common within the tech industry. Companies aren’t obligated to disclose essential information in the proprietary nature of their AI development, including labour practices in the AI supply chain and procurement of materials or rare minerals. Digital rights activists tell us how data privacy and surveillance are affecting our most vulnerable communities as well as wider society.

These issues are systemic, touching many different policy points. They’re best addressed through thoughtful coalitions and the important, painstaking work of activism to advocate for change and to put pressure on government and Big Tech to address them.

There’s a clear role for government. As Matt Davies explains on behalf of the AI Now Institute, "instead of assuming that any and all types of AI will produce economic growth and societal surplus with minimal state intervention, government needs to develop a clear articulation of what ‘public benefit’ looks like in the context of AI and what sort of AI sector will deliver it. It also needs to understand how AI – as a general-purpose technology influencing the development of other sectors – impinges on other long-term priorities such as environmental obligations and the concentration of power in the digital economy."

Part 2: What role does AI play in climate, nature and human rights?

Climate and energy

AI is being used to address the climate emergency and reduce energy consumption in various ways. For example, the UN talks about improving prediction modelling for how climate change is impacting our societies using machine learning and predictive AI. Other companies are using similar technologies for helping prevent wildfires, promoting reforestation or improving early warning systems. AI is also playing an important role in improving the efficiency of batteries and distributing the load on power grids, developments that are essential for infrastructure decarbonisation.

However, none of these are using generative AI for positive climate action, nor to tackle the rising energy consumption required by new data centres. And accurate data about the whole-life impact of generative AI models remains extremely difficult to access, despite the efforts of campaigners like Sasha Luccioni to develop assessment models, largely due to the lack of access to data from Big Tech companies.

Extractive industries and data-hungry AI contribute to the climate crisis

Journalists from across the environmental and tech sectors repeatedly emphasise the significant energy consumption associated with generative AI models like ChatGPT. They point out that the energy and water usage to run and cool data centres is growing exponentially because of AI, and that by 2027 the sector will have the same annual energy demand as the Netherlands. Data centres worldwide are responsible for 1-3% of global energy-related GHG emissions (around 330 Mt CO2 annually), mainly due to the massive energy demands required to maintain server farms and cooling systems.

The number and size of data centres is rising sharply, reaching around 11,800 by March 2024. Energy use by data centres is climbing in parallel, with electricity consumption expected to more than double by 2028. Generative AI is a significant factor in this trend. Although Big Tech firms often make big claims about their use of renewable energy, these don’t take into consideration the additional overall demand associated with their operations and the displacement effect, whereby new sources of renewable energy are taken up by tech companies and are not available for domestic or other industrial use. Between 2017 and 2023, all additional wind energy generation in Ireland was absorbed by data centres, for example.

The growth of AI and associated energy demands is therefore creating new incentives for the use of fossil fuels and may even be driving demand for new nuclear power. In January 2025 the UK government announced the creation of a new AI Energy Council "to understand the energy demands and challenges which will fuel the technology’s development," including the possibilities of new nuclear power in the form of small modular reactors. Fossil fuels are still responsible for meeting over 80% of our global energy needs. Although the energy mix in some places is increasingly renewable, other places remain largely dependent on approaches emitting high levels of CO2. Given that data can be moved around the world quickly and easily, Big Tech companies are likely to build data centres wherever it’s cheapest for them — and it may be cheapest to consume electricity in places which have the fewest rules around energy mixes.

Big Tech companies aren’t yet required to reveal energy mixes powering their data centres, and reporting on emissions and resource use isn’t presented in a way that makes it easy to have a clear picture. Moreover, the same companies promoting AI-led climate solutions are also promoting their AI systems to the fossil fuel industry to optimise the extraction of resources previously considered unviable. And not only is Big Tech actively marketing AI technologies to oil and gas companies, but those companies are also entering the energy generation market, due to the huge energy requirements of data centres. This is a lose-lose situation for the environment.

Progress made on reporting environmental impact

The European Union is implementing legislation designed to help with external oversight and verification of emissions data. In 2024 the European Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) came into effect, mandating that large companies report on social and environmental risks and impacts of their activities. This directive explicitly includes impacts within a company’s supply chain.

In addition, the European AI Act requires companies to provide information about the environmental impacts associated with AI foundational models. Just as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has had a significant impact on privacy and data security for normal citizens, such legislation can shift the conversation on the responsibilities of Big Tech around its environmental impact.

Nature and environment

AI can be used to help with everything from conservation efforts with endangered species through to dealing with controlling pests such as the desert locust. In these cases, AI usually takes the form of object detection and tracking, computer vision and machine classification. This is often combined with cloud computing, analytics and satellite intelligence to provide insights for farmers, activists and conservationists to take action. Most of these innovations rely on advances in predictive, rather than generative, AI.

Resource consumption and pressure on water

While the energy consumption of data centres for both predictive and generative AI is an increasingly mainstream issue, the related issue of resource consumption receives less attention, and there's a lack of reliable data to monitor the issue. However, data centres use freshwater for cooling, and the explosion of generative AI technologies has exacerbated freshwater scarcity in many areas. The trend shows no signs of slowing. According to the UN Environment Programme: "It is estimated that the global demand for water resulting from AI may reach 4.2–6.6 billion cubic metres in 2027. This would exceed half of the annual water use in the United Kingdom in 2023. Semiconductor production requires large amounts of pure water, while data centres use water indirectly or electricity generation and directly for cooling. The growing demand for data centres in warmer water scarce regions adds to water management challenges, leading to increased tension over water use between data centres and human need."

Local communities in areas where data centres are built have to deal with a variety of ecological and social issues due to this resource consumption. People, farm lands, natural areas and ecosystems suffer as Big Tech works to hide its water usage. Data centres are competing with these local communities and ecosystems for scarce water resources, especially in regions already experiencing drought. Water stress also poses a threat to biodiversity in these vulnerable areas.

The destructive nature of rare minerals extraction, e-waste and land degradation further threatens biodiversity and socio-political stability. As Dominique Barron explains, "AI systems rely on the extraction of raw materials such as cobalt, tungsten, aluminium, lithium, and other metals. These are used to create the computing chips that AI systems run on. Although such chips aren't unique to AI technologies, as developers aim to build faster and faster AI systems, they look to more specialised chips such as GPUs (Graphic Processing Units), which offer significantly more compute power than standard CPUs (Central Processing Units). With the exploding hype for AI, there has been an increase in demand for these specialised chips [...]. Mining of these materials has significant human and environmental impacts. For example, the mining of minerals such as cobalt, copper, and tungsten is directly leading to exploitation, violence, and displacement of people in the Democratic Republic of Congo. As the demand grows so too does the expansion of mining operations for the benefit of companies and consumers in the Global North at the expense of people and the environment in the Global South."5

Planned obsolescence with consumer-focused technology and the sheer amount of processing power required for generative AI are increasing waste and pollution as well as impacting human health. The accelerated development of AI technologies means that, as more tech companies embed AI into hardware, more electronic waste is generated.6 There are also displacement effects here, as the key minerals and metals needed for AI expansion are “nearly the same” as those required for transition to a low-carbon economy, putting AI in direct competition with emerging renewable and battery technologies.

Clean technology and innovative, cyclical solutions in resourcing, backed by clear regulation and international standards, are critical in the protection of biodiversity.

Rights and justice

Machine learning, image recognition systems and predictive analytics can be used to work on a number of issues related to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For example, issues relating to hunger, education, health and wellbeing can be addressed in part by AI technologies. We’re beginning to see innovative uses of AI, such as helping to identify or predict illnesses as well as showing us ways to reduce food waste.

However, good examples of how generative AI is supporting such progressive initiatives are harder to come by. When it comes to rights and justice, it’s much easier to unpack how generative AI is causing harm.

Exploitative practices and disinformation worsen under AI boom

Increased resource use by Big Tech and in the technology sector more generally already disproportionately affects communities already on the frontlines of the climate crisis. These communities are often also disadvantaged by poor technological infrastructure, lower levels of digital literacy and inadequate legal frameworks to protect vulnerable communities. To ensure that these communities have fair access to AI technologies and can benefit from them, we have to address systemic inequalities and avoid sowing deeper divisions.

Alongside the more visible issue of resource use, a slew of discriminatory and exploitative practices are made worse by the AI boom. While AI is novel, it often "seems to continue long-standing paradigms of technology in the service of capital, reducing agency and autonomy, increasing the precarity of labor, undermining the well-being of workers, and amplifying forms of racialized and gendered inequality."

The waste and pollution, ecosystem collapse and worker exploitation associated with AI advances disproportionately impact the communities who are already most vulnerable to the climate crisis. It’s a form of environmental colonialism when lower-income countries bear the brunt of technological advancements while richer countries reap most of the benefits.

Critically, generative AI has the potential to make disinformation about climate breakdown vastly easier, quicker and cheaper to produce, while also enabling it to spread further and faster. Social media companies have shown declining interest in tackling this issue. The toxic combination of opaque social media algorithms, polarising social bots and a new generation of AI-generated content is perfectly placed to accelerate a “perfect storm” of mis- and disinformation, in the context of a wider assault on the democratic institutions responsible for safeguarding rights and freedoms.

Civil society organisations and communities must continue to sound the alarm about the ties between AI development and extractive practices, and in holding Big Tech to account for its role in spreading disinformation.

Part 3: Principles

We're sharing these principles so that activists and campaigners of all types can use them as a starting point for your own work. We hope that you’ll engage with the principles and related guidance to help navigate the dilemmas of AI use, as well as communicate your approach and choices effectively — both to your supporters and the wider public.

7 principles

- Curiosity around AI creates opportunities for better choices.

- Transparency around usage, data and algorithms builds trust.

- Holding tech companies and governments accountable leads to responsible action.

- Including diverse voices strengthens decision making around AI.

- Sustainability in AI systems helps reduce environmental impact and protect natural ecosystems.

- Community collaboration in AI is key to planetary resilience.

- Advocating with an intersectional approach supports humane AI.

Unpacking the principles

To explain what each of these principles might look like in practice, the following sections explore them through the lens of problems, opportunities and solutions.

At the end of each section are 3 boxes labelled “responsible practices,” “advocating for change” and “policy recommendations,” where appropriate. These suggestions aren’t exhaustive, but the aim is to use them — and build on them — as a starting point for discussion:

- Responsible practices: practices that all organisations should follow in order to use AI responsibly. These will be most relevant to digital leads or advisors and compliance officers.

- Advocating for change: ways that campaigners and activists can push for the ethical use of AI. These will be most relevant to people in policy, communications and community engagement roles.

- Policy recommendations: policies that governments and other decision-makers should implement to better regulate AI and Big Tech. These will be most relevant to people in advocacy and campaigning roles. They could also serve to guide coalitions of organisations campaigning for change.

We’re aware that, as there are many different sizes and kinds of organisations operating in this space, recommendations and policy suggestions will be more relevant to some than others. However, the important point in the discussion at the intersection of AI and environmental impact is to do what you can.

The principles are as relevant to Big Tech as they are to campaigners and activists. Responsible practice is positive whether enacted by a tiny organisation or amplified by a huge transnational company. Activists alone won’t change the course of Big Tech. An important first step is for civil society to better understand the implications of unfettered AI development, to have a voice in the debate and to influence governments for better regulation and big companies to be accountable for their behaviour. We hope these principles will support this intention.

1. Curiosity around AI creates opportunities for better choices.

As described above, AI isn’t one thing but rather a complex system of technologies that have been collapsed into blanket narratives in our society.

The first principle therefore encourages us to recognise that there are types of AI that can help us find new and innovative solutions to problems we already face. Viewing this conversation from a perspective of learning and curiosity, and with a sense of playfulness, can help activists recover their agency in an ever-complex technological and social landscape. Working with communities to discuss, question and explore how they can or want to use AI, and, more importantly, whether a project should be using AI at all, are essential steps in the ethical use of AI.

I think it's also about discernment, especially when a lot of AI tools have heavy marketing behind them and also rely on this hyper-legitimacy that technology is afforded in our era of modernity. So there's a lot to be said about being both curious, but also discerning about the material reality versus the marketed claims of these tools.

(Marie-Therese Png, Research Scholar, Institute for Advanced Studies)

AI is an increasingly divisive, strange and intriguing set of technologies. Encourage critical thinking about AI use in your communities, discussing and questioning its use and, where appropriate, exploring simpler, more sustainable alternatives. What’s a “worthwhile” application for you?

Responsible practices

- Encourage curiosity and open discussions about AI and the environment with your audiences. Place the use of AI in context, and help people understand the importance of questioning its use. mySociety’s AI Framework is a great example of this practical, open working.

- Question the use of AI and, when possible, advocate for simpler, more sustainable alternatives. Consider whether AI is the right tool for the task or whether a simpler solution like a search engine could be used. This is particularly important in image generation, as generating images with AI can use considerably more energy than searching for an existing image.

- Research and experiment with independent or open-source generative AI services. Ensure that your guidance around AI has a version number and/ or a date for the latest revision, so that people know how up-to-date it is.

Advocating for change

- Campaign for policy making that distinguishes between different types of AI and reduces reliance on energy-intensive computing. Make the case for a “proportionate” approach, challenging the narrative that AI is the only solution to societal problems.

- Highlight examples of communities successfully using AI to solve local problems, sharing stories that inspire others to approach AI with a questioning mindset. Our 2024 AI and Community Action lab is a good example of this approach.

Policy recommendations

- Advocate for distinctive regulation based on the type of AI in use — for example, more restrictive policies for generative AI and more nuanced policies for predictive AI.

- Encourage the requirement for AI providers to provide transparent, plain-language explanations of how their tools work, with a focus on enabling critical public engagement.

2. Transparency around usage, data and algorithms builds trust.

Transparency is essential to support regulation that can address the environmental impacts of AI. It’s also a requirement for public trust and to ensure accountability. Transparency helps us make informed decisions. This means greater transparency in how AI is developed, trained and used, as well as in how we as environmentalists and campaigners are using AI, can have a profound impact on how technology influences our climate and our societies. AI systems are often also embedded in and function as part of other systems, which can make it difficult for users to identify when they’re interacting with an AI technology.7

Big Tech companies make bold claims about their sustainability practices, but in reality their use of resources is, for now, impossible to accurately calculate. Without clear data it's challenging to define and advocate for policy that could reduce their climate impacts. In the research for the Engine Room’s pioneering 2022 report on digital rights and climate justice, researchers noted: "as companies transition to renewable energy sources, interviewees emphasised the need to pay attention to ‘greenwashing’ and to scrutinise corporate sustainability pledges by technology companies, which might only be a drop in the bucket compared to the full range of harms caused."

Only through full disclosure can we understand the intricacies of how technology affects us.

Staff are free to use AI tools if they wish for their own work, but are asked to make it clear to others when they do so, including in any work we publish.

(Hannah Smith, Director of Operations, Green Web Foundation)

Responsible practices

- Be open about how your organisation uses AI, and share information about the environmental impacts of AI to educate your audience, encouraging them to demand openness and honesty about AI usage. For example, see Appendix 2 where we discuss our use of AI for this paper and CAST’s advice for charities and non-profits.

- Develop internal guidelines to evaluate the sustainability claims of AI products or services before adopting them.

- Take a stance of compassionate curiosity when reviewing other organisations’ use of AI. We all have different amounts of knowledge, experience and understanding when it comes to this fast-moving area. Don’t troll, be kind!

Advocating for change

- Expose and counter misleading claims about the environmental benefits of AI, and place all environmental impacts in a clear-eyed context. Work to ensure accurate and transparent communication about AI's environmental costs and benefits.

- Advocate for community-led audits of AI systems to assess their real-world effects, particularly in vulnerable regions disproportionately affected by data centres or resource use.

- Amplify public pressure on tech companies to publish comprehensive reports on energy consumption, data usage and supply chain impacts. Often companies don't provide granular enough data to make truly informed decisions.

Policy recommendations

- Require public reporting on energy use and emissions by the technology sector. Demand that tech companies segment their energy and emissions reporting to clearly indicate resource costs of AI expansion.

- Mandate independent assessments of sustainability claims made by technology companies, with penalties such as fines for misleading practices. Establish international standards for measuring and disclosing the environmental footprint of AI, ensuring consistent accountability for their supply chain across all regions. The UN Environment Programme has made specific policy recommendations for member states in this area.

3. Holding tech companies and governments accountable leads to responsible action.

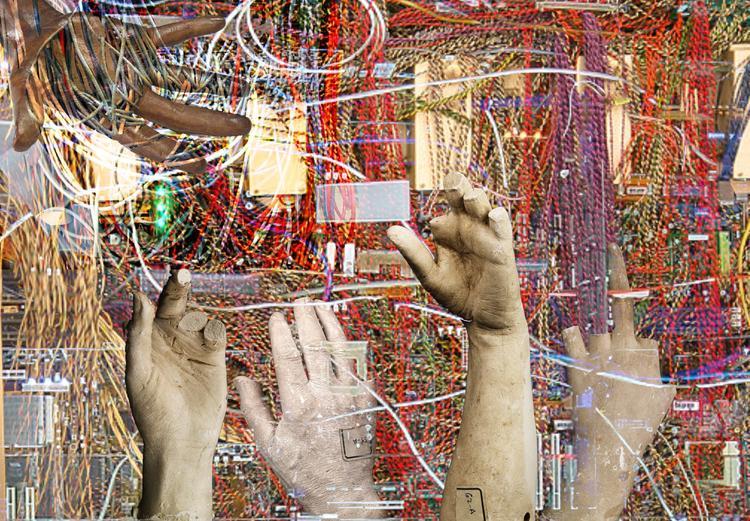

A lack of transparency means that tech companies not only make confusing and empty claims about their emissions and resource extraction, but “creative” accounting when it comes to the reporting of emissions is also a widely utilised tool to skirt accountability. The human impact is obscured, leading to further environmental exploitation and detriments to workers’ rights. From mining to human large language model (LLM) training tasks like labelling or keywording, the lifecycle of all technology is built upon human labour.

Hugging Face, the AI community platform, allows for the public reporting of LLMs’ energy consumption, but voluntary reporting only goes so far. Governments need to apply safety and transparency regulations, with strict consequences for non-compliance. Campaigners could promote holistic assessment and accountability frameworks to help examine wider societal and environmental impacts. These would extend beyond carbon emissions to include resource extraction and social impacts.

Given the sums of money and scale involved in building infrastructure and policies around generative AI, the majority of action needed has to come from nation states. However, there are roles for individuals, NGOs and other ethically-minded organisations. We must work together to take collective action, putting pressure on Big Tech and governments to put in place frameworks and regulations that protect individuals and our environment.

Some of this work may happen around the burgeoning area of "AI literacy". It's important that digital rights campaigners and environmental activists play a role in the conversation, to help foreground salient issues and to help define what it may mean to be truly "AI literate".

Responsible practices

- Seek to understand the social and environmental impact arising from AI use. Develop and maintain an organisational AI policy that details the choices you make on AI usage and incorporates sustainability choices. Share your policies openly to help others make responsible choices. Report against your policies, and highlight where a lack of transparency from tech companies is making your efforts difficult. AI risk assessment tools, such as the one developed by the Wildlife Trusts, might help.

- Find and work with peers facing the same challenges. (In the UK, CAST’s Digital Leads network is a good place to start.)

- Question suppliers in the procurement stage of AI services about how they’re measuring their impact as a condition of purchase. Green Web Foundation has published advice on how to ask for data from suppliers.

Advocating for change

- Draw attention to the environmental impacts of AI, holding organisations and AI companies accountable for their practices. Use these opportunities to encourage your audience to develop AI literacy, critically assessing the sustainability claims of AI technologies and supporting responsible practices. Joseph Rowntree Foundation has provided a useful briefing on AI literacy — what it is and why it matters.

- Promote holistic frameworks that assess societal and environmental impacts, highlighting the hidden costs of AI systems such as resource extraction and labour exploitation. Expose greenwashing and challenge misleading claims about AI’s environmental benefits.

- Use examples from human, labour and digital rights policy and other justice initiatives to establish accountability positions that are proven to work (such as Friends of the Earth’s Planet over Profit campaign).

Policy recommendations

- Mandate independent audits of AI systems, requiring companies to disclose the full lifecycle impacts, including emissions, resource usage and labour conditions. Implement laws that require accurate and comprehensive emissions reporting, closing loopholes for creative accounting practices.

- Demand due diligence in governmental oversight of AI production and supply chains. Ask for clear protocols about who's responsible when AI causes harm or fails to perform as expected, ensuring human oversight remains part of decision-making processes (ie "human-in-the-loop").

- Campaign for government funding for initiatives to advance "AI literacy" education, ensuring that it includes discussions about ethics, environmental impacts and social justice considerations. UNESCO’s competency framework for teachers and students is a good start.

4. Including diverse voices strengthens decision making around AI.

Like other technologies developed by Big Tech companies, there remains a persistent challenge of limited inclusivity in AI development and use. This is not only discriminatory but also obscures the very real power dynamics associated with AI technologies. It perpetuates existing biases and inequalities due to what’s included or excluded from training data, the locations of human labour used to help “correct” the models, and who has access to the latest developments. There are also issues relating to access and consent. Unequal access to the use of and conversation around AI development neglects local knowledge and cultures.

Language and localisation is, at its core, an issue of inclusivity. So AI development being predominantly English-centric and based in richer countries means it doesn’t represent our global community. LLM training data is usually based on the somewhat indiscriminate ingestion of mass amounts of data, using datasets that represent the good, the bad and the ugly of human discourse and bias. As LLMs tend to be "black boxes," it's difficult to know exactly what's been included in their training data. As a result, digital rights activists often can’t identify the sources of bias. Not only does this lead to the misrepresentation of non-Western cultures, but these biases and inequalities in AI can also result in feedback loops, when new material created using AI is then used as training data for new models, further entrenching bias and potentially leading to "model collapse".

While genuinely new insights have been created by generative AI, such as new mathematical proofs, we are still in the foothills. As the author of "Resisting AI," Dan MacQuillan explains: "the process of training AI takes the intersectional entanglements of society and culture and distils them into impenetrably large models. Its inferences are giant engines for rehashing the status quo into amenable representations, not for generating genuine insights."

We can alter this narrative by integrating multiple viewpoints into discussions around AI development and use. New pre-training tools and smaller open source models are beginning to see light, helping pave the way for less resource-intensive and more focused models. For example, unpacking Indigenous approaches to ways of being and understanding could help us formulate more inclusive narratives.

[I]f we take a climate justice lens, how might communities most adversely affected by climate impacts contribute to and shape conversations about the development of AI? How might the planet itself be a stakeholder in AI creation and decision-making processes?

(Ellie Hale, Co-Executive Director, Catalyst)

Engaging authentically with diverse communities means that AI-based applications can reflect a broader range of experiences and address the social needs beyond the usual suspects. We need ethically informed, inclusive decision-making processes, which explicitly ask for the consent of those who'll be affected by those decisions. This will empower communities to shape a future, with or without different forms of AI, in a way that’s equitable and just.

Again, for inclusivity to play a central part in the development and use of AI, a storytelling approach is useful:

...one effective strategy I've seen is the use of storytelling to bridge the technical and non-technical worlds. Simplifying complex concepts into relatable, human-centred narratives allows non-specialists to grasp the real-world impacts of AI.

(Eric Zie, Founder and Advisor, CR&A)

This can help those outside the field of technology to begin to comprehend the practical impacts of AI. Given the billions of dollars involved in AI, these initiatives should be funded by Big Tech companies, helping ensure that their products and underlying technologies can serve a broader spectrum of society. This is an opportunity for activists and a place to enforce accountability.

Being inclusive is an intentional act incorporating a range of perspectives to help ensure that marginalised voices are listened to. To help build fair and equitable societies, we must work to prevent further bias and existing inequalities from being entrenched in AI systems.

Responsible practices

- Ensure that your conversations and policy development include and amplify diverse voices, particularly those from marginalised communities such as low-income workers and people of colour. Use AI models that have been tested for bias, for example using a toxicity classifier.

Advocating for change

- Build partnerships with marginalised communities to ensure their perspectives are included in AI development, particularly those most affected by climate impacts or social inequalities. Adopt participatory consent processes to include these communities in decision making about AI applications that directly affect them.

- Engage with and incorporate feedback from communities most affected by AI deployment, including workers, making certain their voices are heard in decision-making processes. Use storytelling techniques to translate technical AI concepts into relatable narratives, enabling broader community engagement and input.

- Promote open-source AI models and tools as a means to decentralise development and reduce resource inequalities, making AI more accessible globally. Expose bias. Advocate with marginalised communities, and don’t exacerbate systemic inequalities through AI models.

Policy recommendations

- Campaign for regulations requiring transparency in AI training datasets, with mandatory inclusion of diverse cultural, linguistic and geographic perspectives. For example, the CVQA benchmark dataset tests an AI model’s ability to answer questions related to culturally relevant images.

- Push for funding programmes, paid for by Big Tech, for smaller, open-source AI projects that prioritise inclusivity and ethical design principles.

- Lobby for legislation mandating that companies consult affected communities during AI development, particularly when deploying systems in regions with unequal access or historical marginalisation. This is particularly important when deploying AI for public services.

5. Sustainability in AI systems helps reduce environmental impact and protect natural ecosystems.

We’ve laid out the issues associated with the energy and other resource use of AI expansion in the introductory text of this paper. There are certainly "transformative opportunities" for the environment in areas such as climate modelling, nature protection and pollution prevention. If the latest press releases and breathless news articles are to be believed, AI will soon fix everything from climate breakdown to previously intractable social issues. Big Tech wants us to think we need to focus on AI first and everything else comes later, in particular our climate and nature goals. Betting on untested technologies, at the expense of the solutions that we know are already available, clearly illustrates how the profit motive overrides all other considerations for Big Tech, in particular environmental concerns.

In addition, most of the use cases associated with "AI for good" are based on predictive rather than generative AI. That's not to suggest that generative AI won’t deliver sustainability benefits in the future — and some studies have argued that the use of AI to carry out tasks including writing and illustrating produces fewer emissions than using humans to complete the same functions. However, this analysis doesn’t take into account the social context in which these choices are made, and the ways in which growing efficiency and demand could generate further environmental costs (an example of Jevons paradox). Moreover, since AI technologies are primarily aligned with the accumulation of profit and the acceleration of unsustainable lifestyles, their deployment has knock-on impacts for human behaviour and patterns of consumption, incentivising and promoting harmful choices.

In thinking about the sustainability principle as a society, we therefore need to consider a number of different domains. First, we need to take a whole life-cycle approach to both software and hardware. In hardware, this means thinking about every stage of the process, from mining and extraction of the materials, to manufacturing and data centre construction, to end-of-life reuse and disposal. For software, this means considering the consequences of data collection through model training and deployment to maintenance and retirement. In addition, for both software and hardware there are direct, indirect and higher-order effects to consider. Direct effects include the consumption of energy and resources, whereas indirect effects refer to the increased environmental damage that may be associated with the use of a new tool or process (for example, increasing traffic levels on quiet residential streets due to "optimisation" of route planning). Higher-order effects refer to the ways in which AI use may exacerbate existing inequalities, due to the under- or mis-representation of marginalised groups in training data, for example (as explained in principle 4).

We should be promoting energy-efficient AI models and adopting an approach that reduces environmental and societal harms at every stage of AI’s lifecycle. The recommendations offer some first steps, but this is a fast-moving area, and finding peers grappling with similar issues can be an important tool to support both the adoption of responsible practices and the development of a collective voice in the sector. It’s also important to recognise that this is a structural issue. Individual or organisational "choice" is no substitute for effective regulation in this area. We need to shift the rules of the game and then use transparency to ensure compliance, rather than pushing the burden of this research down to small, resource-stretched non-profits.

Responsible practices

- Prioritise use of energy-efficient AI models, algorithms and hardware. Large models consume more energy, so finding smaller, more efficient architectures can reduce environmental impact. Green Web Foundation has a summary of how organisations can (or can’t) mitigate environmental harms when choosing to use AI.

- Use local models whenever possible. In Appendix 3, we’ve included a brief explanation as to why and a quick guide to help activists and campaigners get started.

Advocating for change

- Push suppliers and other relevant partners to implement policies to minimise negative impacts at each stage, including responsible sourcing of materials, waste reduction and circular economy principles. The European Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) mandates that large companies report on social and environmental risks and impacts of their activities. It explicitly includes impacts within a company’s supply chain.

- Highlight the hidden environmental and societal costs of AI systems in campaigns, pushing for a more balanced narrative that addresses both benefits and harms. As part of this, raise awareness of the existence of energy-efficient AI models and the use of renewable energy sources. Advocate for a responsible approach to AI that minimises environmental harm and protects natural ecosystems.

Policy recommendations

- Propose the enforcement of rules around the use of renewable energy sources for AI infrastructure and data centres. These should be based on a principle of "additionality" not "substitution" (renewable energy for AI shouldn’t reduce the supply of renewables for other industrial and domestic uses).

- Require developers to adopt strategies that help reduce the environmental impact of AI systems, such as optimising energy consumption during model training, using life-cycle assessments (LCAs) for AI projects and adopting energy-efficient hardware and algorithms. These principles focus on reducing AI's carbon footprint while maintaining performance.8

- Hold companies to account using existing legislation, and ensure human-centric principles when drafting new legislation.

6. Community collaboration in AI is key to planetary resilience.

In principle 4 we note the need for including diverse voices, but that can be challenging to achieve. Communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis face barriers to meaningful participation in AI development and decision making, while developers often ignore the need for community involvement and the social dimensions of technological advances.

There’s significant potential to enrich AI development by integrating community perspectives, especially from those most affected by technological changes. Initiatives can harness grassroots participation to shape AI solutions that are culturally relevant and socially beneficial. By including diverse community voices, a more comprehensive understanding of AI's potential impacts can be achieved, leading to more informed and balanced decision making.

To address these challenges, it’s important to establish channels for genuine community participation. As discussed earlier, this involves ensuring access to relevant information and the opportunity for people to provide free, prior and informed consent to how their data will be used and stored in any AI-based systems. Developing shared principles and guidelines that prioritise transparency, equity and inclusivity will empower communities to actively contribute to shaping AI solutions that align with their values and priorities. By encouraging open dialogue and collaboration, AI can become a tool that genuinely serves diverse communities, contributing to more equitable and effective outcomes.

Furthermore, using storytelling can help distil complex AI concepts into relatable, human-centred narratives, facilitating broader community engagement and comprehension.

Environmental standards and commitments to free, prior and informed consent offer grounded responses to ideologies of infinite growth that yield high profit for some and devastating consequences for many. The free, prior and informed consent of communities is only possible when we are able to ensure meaningful access to information and participation in decision making.

(Shawna Finnegan, Environmental Justice Strategy Lead, Association for Progressive Communications)

Technology is a tool communities can use to bring about a better world, but it’s solidarity that gets us there. Encourage AI development to take place according to the needs of communities and our planet, not just market forces.

Responsible practices

- Incorporate principles of free, prior and informed consent into data collection and AI design, allowing communities to make fully informed decisions about how their data is used.

Advocating for change

- Share and promote initiatives that seek to simplify understanding and choice around generative AI tools, such as the AI Risk Assessment from the Wildlife Trusts or the CAST AI Experimentation Canvas.

- Advocate for public and private funding to facilitate grassroots participation in shaping AI solutions that align with cultural and social priorities. Democracy Next’s proposal for local and regional AI public assemblies to inform decisions about applications is one example of the form that participation could take.

- Advocate for funding structures and networks that help non-profits, particularly grassroots organisations, develop or adopt appropriate AI models and evaluate impact. Tech 4 Good South West’s VCSE (Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise) AI peer network is a good example.

- Support campaigns and organisations that champion data rights and prevent extractive practices that harm communities, such as the Open Rights Group, Black in AI, the Algorithmic Justice League and Amnesty International.

Policy recommendations

- Raise awareness of existing legislation and guidance among users and policy makers, such as the UK Department for Education’s product safety expectations for generative AI. Encourage community feedback on proposals and initiatives, and campaign for more citizen input in decisions related to AI.

- Advocate for alternative data governance models that respect digital rights, including Indigenous People’s rights to control their own data, such as the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance or the findings of the Citizen-Led Race Equity Lab (CREL).

7. Advocating with an intersectional approach supports humane AI.

The unintended consequences of technology can be significant, with social inequities and environmental deterioration often intensified, particularly at the intersection of justice and AI. Furthermore, there exists a systemic bias in AI which prioritises English language sources and perspectives, potentially marginalising non-English speaking communities.

There’s significant overlap between the communities that drive forward progressive environmental justice policies and those who advocate for digital rights. In recent years, many tech activists have used their technical skills on behalf of justice-based organisations. These organisations have sought out tech activists to help them mitigate and understand digital rights issues like data security, misinformation and digital attacks.

Tech activists and environmental justice campaigners are forming coalitions like the Green Screen Coalition or the Open Climate Community Movement. Funders and funder networks like the Ford Foundation, the Ariadne Network and the Mozilla Foundation are financially supporting projects and initiatives that aim to shift the environmental impact of technology.

The partnership between environmental justice organisations and digital rights campaigners extends into other areas too. Individuals, communities and organisations are working together towards a more just and humane future, tackling labour, migration, inclusivity and economic issues alongside their environmental work. The non-profit sector continues to push back against historic, social and environmental injustices, recognising systemic issues and holistic interdependencies.

The environmental impacts of generative AI cannot be separated from issues of AI nationalism, platform capitalism, and data colonialism.

(Helen Beetham, Lecturer in Digital Education, University of Manchester)

Digital rights campaigners and environmental justice communities have significant overlaps with other groups. By fostering collaboration across sectors and integrating justice and rights-based frameworks into AI development and advocacy, more integrated pressure can be brought to bear on government and corporate decision makers.

Responsible practices

- Engage teams in ongoing training to recognise and mitigate biases in AI systems, particularly those that marginalise non-English-speaking communities or perpetuate systemic inequalities.

Advocating for change

- Invite your audience to reflect on the broader social and environmental contexts of AI development, moving beyond purely economic perspectives. Help explain the difference between "sustainable AI" and "AI for sustainability".

- Build campaigns that draw attention to the interconnected impacts of generative AI, such as labour exploitation, platform capitalism and environmental harm, creating a unified narrative for change.

Advocate for funders to prioritise intersectional projects that address digital, social and environmental justice, expanding financial support for collaborative initiatives. Demonstrate how collaboration across different sectors and communities leads to more humane and effective AI solutions. - Facilitate dialogues that connect AI with issues of justice, equity and sustainability, and advocate for the development and use of AI to be shaped by these frameworks, rather than economic growth.

Policy recommendations

This section focuses on advocacy rather than direct policy, but recommendations can be inferred from the need to align AI governance with broader frameworks addressing justice, rights and equity. These might include supporting international co-operation on AI ethics and environmental standards.

Conclusion

This paper has addressed the reality of AI’s impact on our environment and our communities. Activists and campaigners are up against immense challenges stemming from market-driven forces, and the overwhelming influx of capital into AI development and marketing is dizzying. Civil society is struggling to figure out how we can make ethical choices when facing big systemic and structural issues exacerbated by unfettered AI development. We need to work together to address the concentration of power in the hands of a very small number of actors. And we must find ways to navigate what’s both an exciting and concerning AI-driven landscape.

Under each of the 7 principles are ways to start thinking about harnessing the widening field of generative AI in our work as environmental justice and digital rights organisations. We hope you can use the responsible practices in your work, and that the principles and recommendations support your advocacy work in finding a common cause and language with partners. You can also add to these as you engage further with issues and policy areas.

We must advocate for policies that guarantee equitable participation and representation in AI design and implementation. We must demand environmental standards and commitments to free, prior and informed consent, to ensure that communities have meaningful access and can engage genuinely in decision making.

We can cultivate an environment where technological advances are developed more fairly, benefiting a broader spectrum of society. Our participation in the technology sector is an ever-more important part of daily activist life, and we should commit to working together and supporting one another as we seek to create positive change in our communities, organisations and governments.

Take this work further:

- Explicitly discuss and build on the 7 principles introduced in this paper, in particular when working with other organisations.

- Check with other related organisations about the work they’re doing in this area, and find ways to work together, for example by setting up peer-learning groups.

- Use the "responsible practices," "advocating for change" and "policy recommendations" boxes under each of the principles in this article to inform your work going forward.

Glossary

Artificial Intelligence (AI) — A field of technology that involves the creation of systems capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence, such as decision making and problem solving.

Big Tech — Large technology companies that have significant influence over market trends and industry standards.

Colonialism — The control or governing influence of one nation over a dependent country, territory or people.

Deregulation — The reduction or elimination of government rules that control how businesses can operate.

Digital rights — Rights related to online activities and access to digital resources, including privacy and freedom of expression.

Dystopian — Pertaining to a society characterised by human suffering, inequality or oppression.

Environmental justice — The fair treatment of all people with respect to environmental policies, ensuring that everyone has equal access to a safe environment.

Greenwashing — The practice of misleadingly marketing products or policies as being environmentally friendly.

Intersectionality — A framework for understanding how various aspects of identity, such as race, gender and class, intersect and influence human experiences.

Large Language Model (LLM) — A type of generative AI model trained on vast quantities of text to understand and generate human language.

Local models — AI models that are deployed and operated on local devices rather than in cloud environments, allowing for options of privacy and energy efficiency.

Open source — Software that allows users to view, modify and distribute its source code, promoting transparency and collaboration.

Planned obsolescence — The practice of designing products with a limited useful life so that they will become obsolete and require replacement.

Solarpunk — A speculative movement that envisions a future beyond scarcity and hierarchy, focusing on community, sustainability and harmony with the environment.

Systemic bias — Prejudices or patterns of disadvantage and inequality that are embedded within the structures and processes of institutions.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Use of quotations

Some of the pull quotes in this article are taken from email interviews and contributions to an invite-only online roundtable discussion held in November 2024. All quotations have been agreed with their authors.

Appendix 2: How we used AI

In accordance with the 7 principles outlined in the article, this appendix is an overview of how we as authors used AI in the course of our research and writing.

In addition to accepting low-level autocomplete suggestions from Google Docs and fixing spelling mistakes, we used a collaborative notebook through NotebookLM. We acknowledge that LLM training is extremely resource intensive and that Google is a company accused of using creative accounting and lobbying to obscure its resource use. We also used local LLMs (models Llama, Mistral and LLaVA) through a macOS app called RecurseChat.

We chose NotebookLM as part of our own learning and experimentation. As well as being chat-based, this technology allowed us to ask questions of up to 50 of the 75+ resources we consulted for this article. Before we loaded resources into the NotebookLM, we scanned them to identify whether or not they were relevant to our research. We then asked NotebookLM questions to help us identify which resources referenced particular themes or data. Once NotebookLM told us where to look, we went to the original resources to pull the information we were looking for. This allowed us to directly reference our sources in a more efficient way.

We used generative AI to generate text sparingly and didn’t use it to generate images at all. A small number of paragraphs in this article started out as AI-generated based on our prompts as a form of placeholder text while we built up arguments in other sections. These placeholders were then deleted, rewritten, edited and otherwise remixed. The vast majority of the article was written and edited without any generative AI.

Appendix 3: Installing local models

As this article details, the amount of water used to cool data centres is staggering. Cloud-based AI models like ChatGPT or Claude contribute to this excessive resource consumption. However, we can install local models directly onto our computers. Using a local LLM requires significantly fewer resources than a cloud-based model. There are other benefits as well such as increasing data security. A locally installed model also allows for offline use when an internet connection isn’t available or is expensive and/or unreliable.

While it can be daunting to think about how to install a local model, there are communities working on software to help non-technical users. There are a variety of software tools like RecurseChat, LibreChat, Poe or DeepL that can make it easier to install and use a local model. Search for any of these tools and download the software to experiment with local models.

In a blog post entitled "Cooperating through the use of AI: Some practical tips to use AI with your team," we’ve written more about local LLMs and provided some links to help people get started.

Acknowledgements

Laura Hilliger and Doug Belshaw of We Are Open Cooperative are the authors of this article, in collaboration with Mary Stevens from Friends of the Earth (England, Wales and Northern Ireland). We’d like to specifically thank Mary for entrusting us with this research, and for her encouragement and feedback.

We’re grateful to have been invited to moderate and participate in the Greening AI Roundtable, in which our 4 experts reviewed and spoke about the first draft principles in this article. Their feedback helped construct the problems, opportunities and solutions discussed. Thank you to (in alphabetical order):

- Marcus Berdaut, Creative Producer at the Upsetters9

- Marie-Therese Png, AI Ethics PhD Candidate at Oxford

- Samantha Ndiwalana, Ranking Digital Rights Research Lead at the World Benchmarking Alliance

- Shawna Finnegan, Environmental Justice Strategy Lead at the Association for Progressive Communications.

We’d also like to thank interviewees we received insightful answers from via email:

- Ellie Hale, Catalyst

- Eric Zie, CR&A

- Hannah Smith, Green Web Foundation

- Helen Beetham, University of Manchester

- Michael Khoo, Upshift Strategies

- Tom Greenwood, Wholegrain Digital

- Yasmin Ibison, Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Mary Stevens would also like to extend her thanks to Dominique Barron and the team at Careful Industries for their research for Friends of the Earth, which has helped inform the thinking in this article.

We're grateful for the support of the Green Screen Coalition in developing this report. This work has been funded by the Green Screen Climate Justice and Digital Rights Coalition as part of the Catalyst Fund. The opinions set out in this report reflect the position of Friends of the Earth alone.

Finally, we’d like to thank the many, many authors and organisations whose reports we reference in this article and which have influenced its development.

Hero image: Hanna Barakat + AIxDESIGN & Archival Images of AI / Better Images of AI / Weaving Wires 2 / CC-BY 4.0

- 1

The “just enough” idea comes from Rachel Coldicutt, whose newsletter can be found online.

- 2

The research for this paper included interviews with environmental justice and digital rights campaigners, as well as an online roundtable event in November 2024. Unless otherwise indicated, the quotes included in this paper are taken from a transcript of the roundtable discussion or extracts from these interviews.

- 3

Barron, D. (2024). Navigating AI-Enabled Futures. Careful Industries report for Friends of the Earth (England, Wales and Northern Ireland). Unpublished.

- 4

Ibid.

- 5

Ibid. It cites Amnesty International.

- 6

Ibid.

- 7

Ibid. It cites research exploring public engagement with AI in the street through a range of systems including cars, cameras, drones, apps and card readers.

- 8

Zie, E., Founder and Advisor, CR&A. Email interview. Conducted by Doug Belshaw (15 October 2024).

- 9

The Upsetters’ research and thinking was developed as part of the "More than AI" sandbox at the Watershed / Pervasive Media Studio, Bristol, in 2024. Find out more.